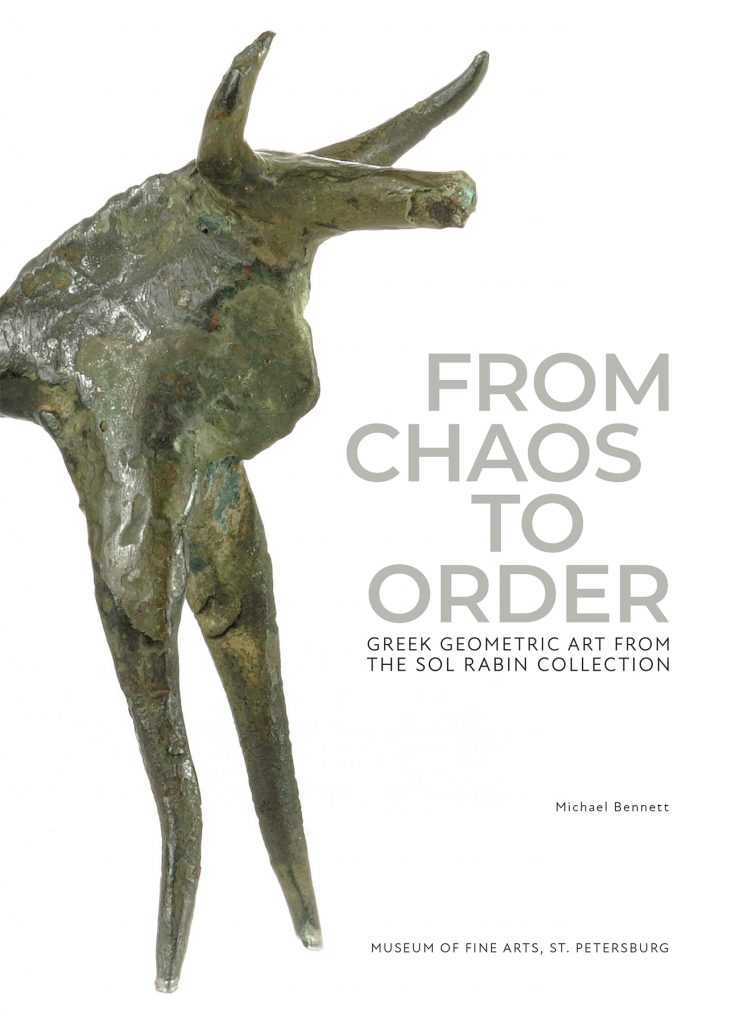

PARADISE | PARADISE – Layered

St. Petersburg Month of Photography and the inaugural Photo Laureate Thomas Sayers Ellis

By Clara ten Berge

Thinking about living in Florida, the lyrics “this could be heaven or this could be hell” comes to mind. The white sandy beaches, the refreshing springs with their captivating flora and fauna, and the rich cultural landscape (as evidenced by this very website), along with the agreeably mild winters, make it a paradise you wouldn’t want to leave.

Yet, when mid-May arrives, the heat slaps you in the face and hurricane season begins, a layer is peeled back to reveal one of Florida’s many other sides. Peel back another layer, and you uncover complicated politics, homelessness, a terrible housing market, raging late-stage capitalism, and more. Florida is a many-headed beast; while it can be paradise for some, it could be hell for others.

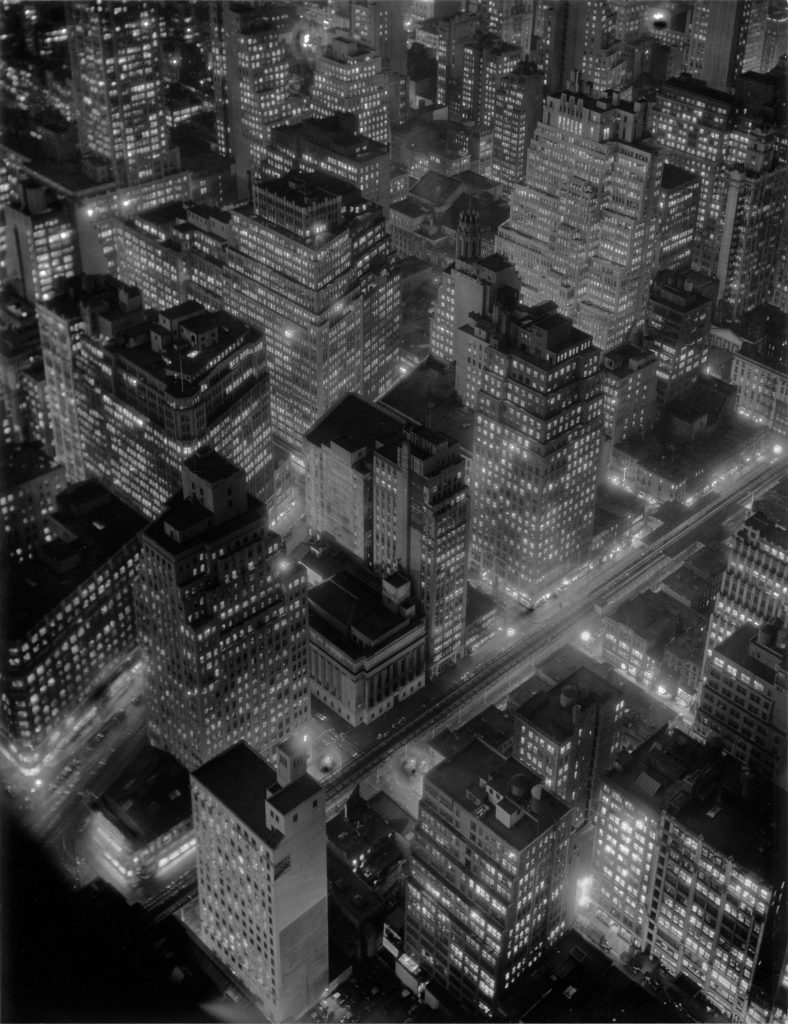

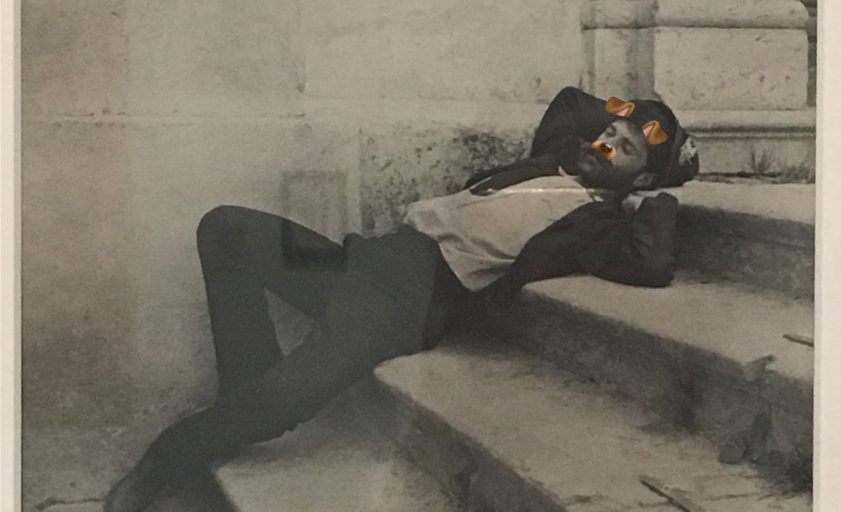

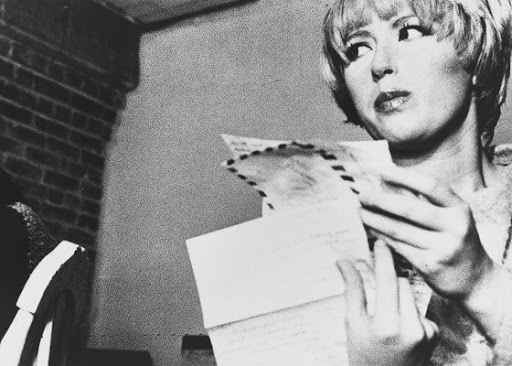

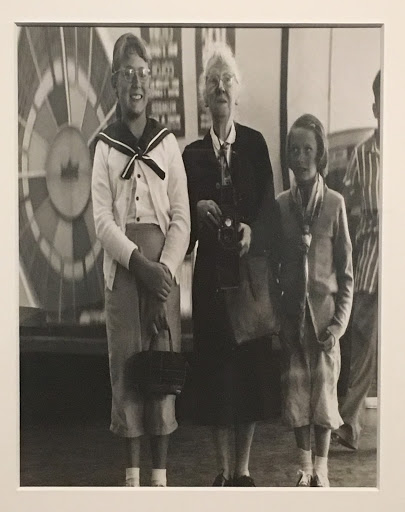

Thomas Sayers Ellis, the inaugural Photo Laureate of the Saint Petersburg Month of Photography (SPMOP), has spent a year walking the streets and unveiling the many stories of Tampa Bay, capturing everything from the blissful and joyful to the mundane, the painful, and the terrible.

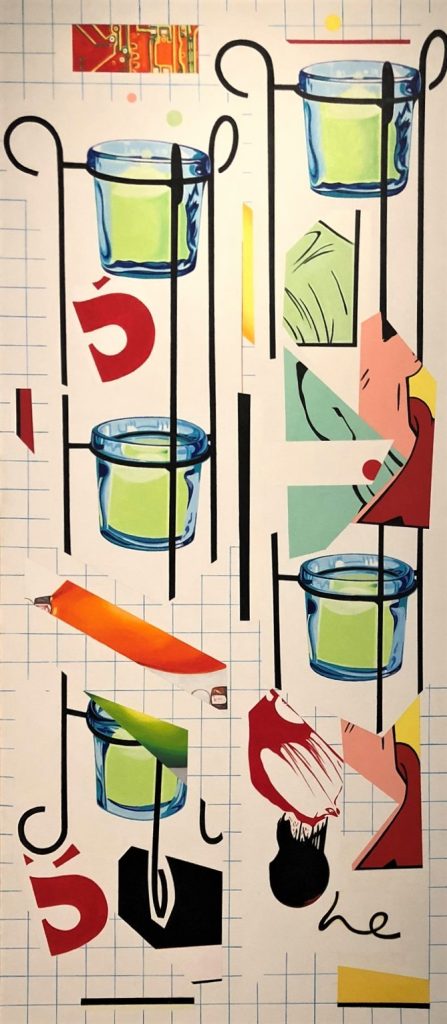

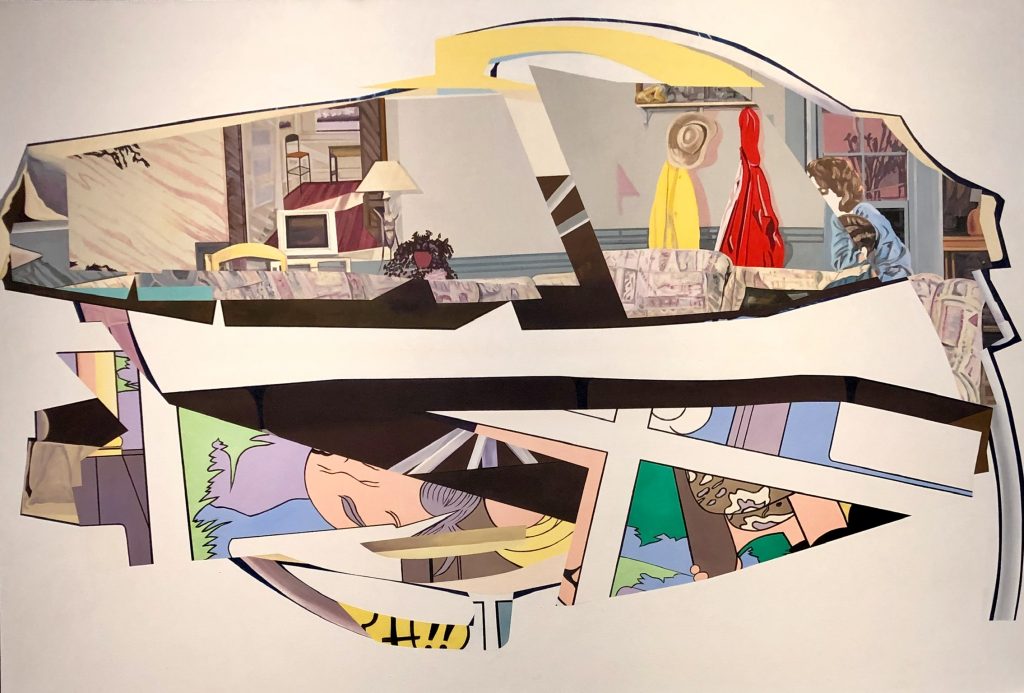

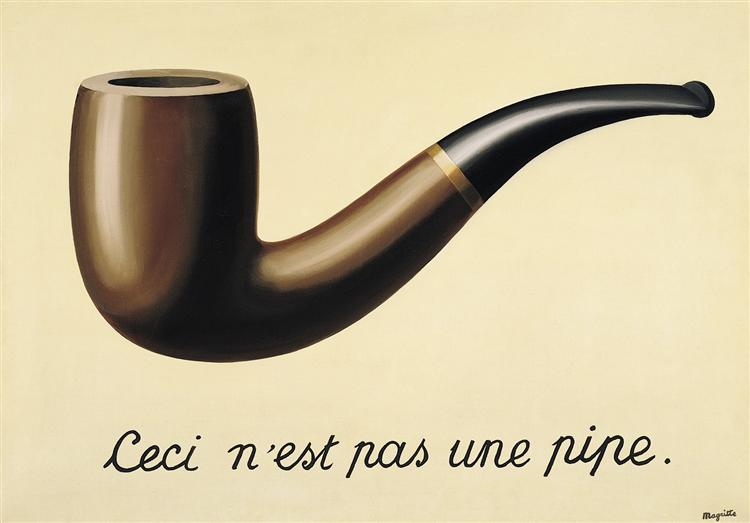

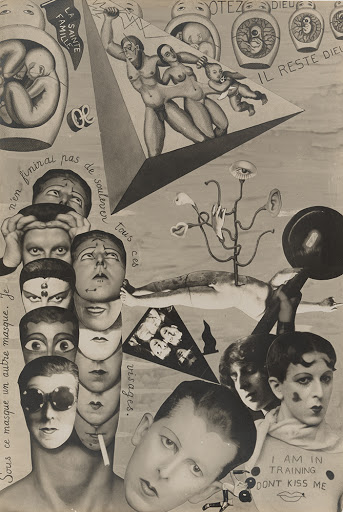

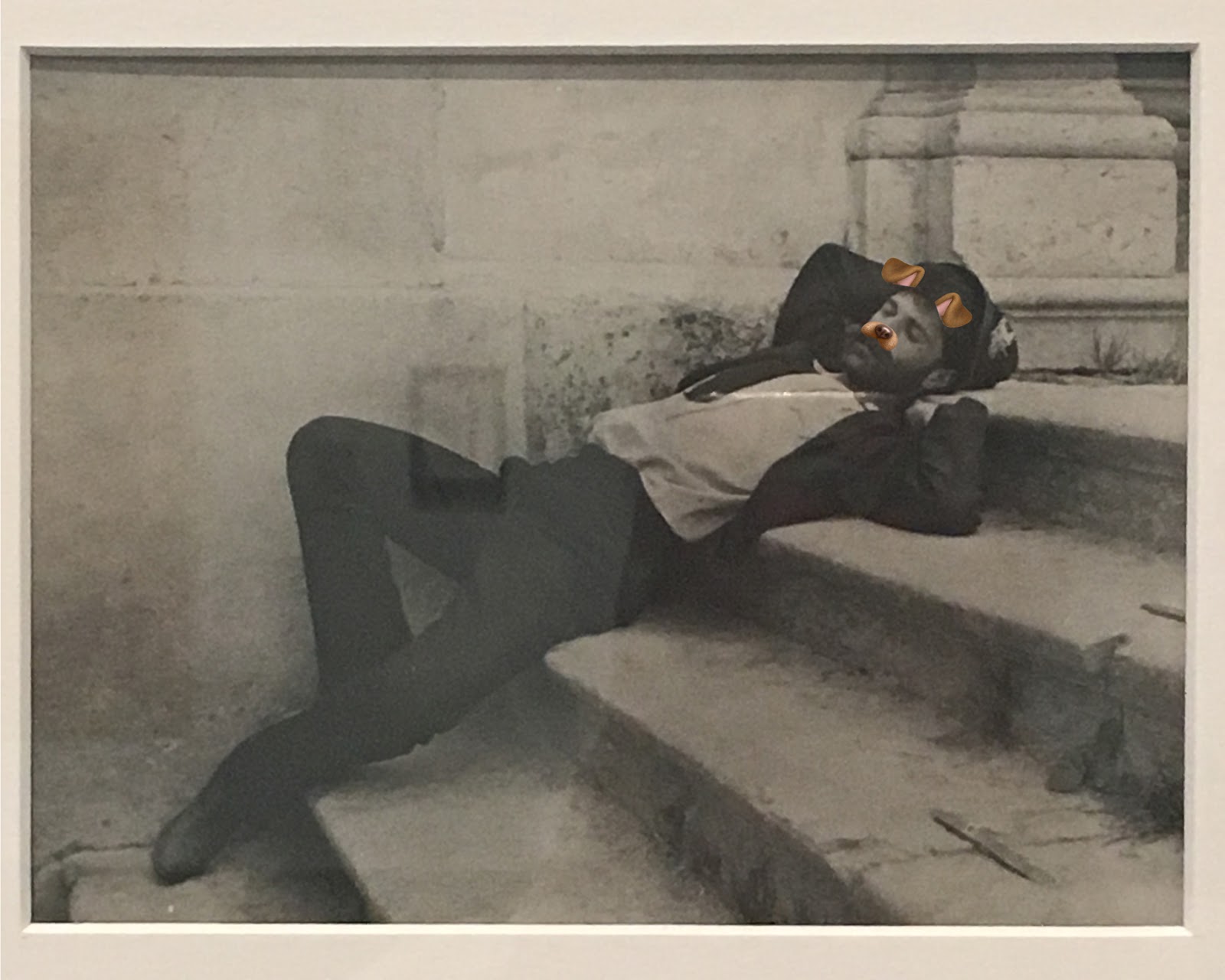

With his images, he creates narratives that go beyond street photography. They are seductive, they will lure you into paradise. They are confrontational, they will show you the fringes that make up your paradise. His images are layered, both in the literal as in figurative sense. They show a different dimension in paradise, a dimension that is made up of advertising, marketing and image building of what paradise should be. But at the same time, this paradise is a construct that is only available for the happy few.

— Marieke van der Krabben, Executive Director, SPMOP

(excerpt from “‘In the Hall of Mirrors, Nothing Is as It Seems,”

foreword to Paradise ǀ Paradise -Layered)

Saint Petersburg Month of Photography

SPMOP, a non-profit founded by photography historian and curator Marieke van der Krabben and photographer Águeda Sanfiz, celebrates local Tampa Bay photography in every way possible. During the month of May, SPMOP organizes exhibitions and events, collaborating with local artists and venues such as the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts in Tampa, and the Morean Arts Center, Five Deuces Galleria, and the Museum of Motherhood in St. Petersburg.

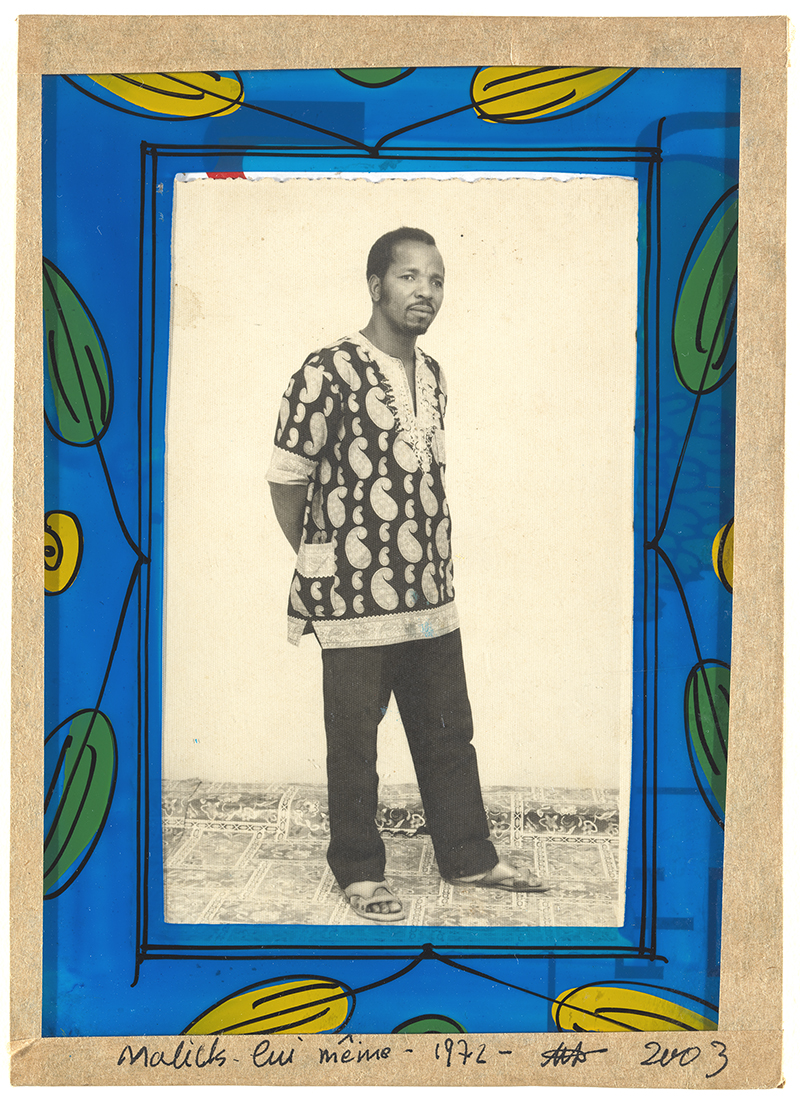

Every year the organization will choose a Photo Laureate, who will have the honor of documenting life in Tampa Bay for a year. In May of 2023, SPMOP announced its first Photo Laureate: Thomas Sayers Ellis. From over 35 artists, SPMOP selected five nominees whose work was exhibited at the Morean Arts Center in Saint Petersburg in May of that year. The jury was captivated by Thomas’s poignant photos that immediately grabbed the viewer’s attention. Each photograph told a unique story and invited dialogue. The panel was convinced Thomas would be able to highlight the many stories of Tampa Bay in new and exciting ways.

It is inspiring to see an artist like Thomas in action. His dedication and enthusiasm are infectious. He is open, polite and friendly when photographing people on the streets. Since he moved to Saint Petersburg in 2016, he is not yet used to the Florida heat, but his urge to document the streets and the people overcomes this obstacle.

Now, at the end of his tenure, Thomas Sayers Ellis receives a solo exhibition at the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts (FMoPA). Opening on June 18th, the exhibition will showcase this year-long project. Using a mixture of black-and-white and color photography, digital as well as film, and accidental double exposures, Thomas has assembled an eclectic collection of images that constructs a multi-layered account of his year as SPMOP’s first Photo Laureate. An accompanying photo book with an extended collection of Thomas’s photographs and poems is currently in the making by SPMOP Executive Director Marieke van der Krabben.

Florida Museum of Photographic Arts

FMoPA’s move to Ybor City has been a game changer. The beloved Photography Museum struggled at its previous downtown Tampa location, surrounded by corporate offices and at an inconveniently high level to attract foot traffic. Since relocating to 7th Avenue, the museum enjoys the warm embrace of the vibrant arts community around it. Residing on the first floor of the historic 1928 Kress Building, the museum is part of Kress Contemporary. Kress Contemporary is the home of many art galleries, art studios and visual and performing arts organizations such as GRATUS, Tempus Projects, Screen Door Microcinema and the Tampa City Ballet. Often on Thursdays, the museum hosts events coinciding with the art initiatives above it, feasting art lovers with double the celebrations.

What sets FMoPA apart is its combination of internationally and nationally renowned artist exhibitions, its celebration of emerging local artists, and its many community programs. This Spring they organized the phenomenal exhibition Joel Meyerowitz: Confluence, 1964-1984 and in July they will open Photo Ybor, about the history of Ybor City. Programs such as Prodigy: Storytelling through Photography and the annual Member’s Show, demonstrate FMoPA’s commitment to their community. Not all museums offer their members and community a venue to exhibit their art, which makes stepping into a place like a gallery or museum more accessible. This layered approach in exhibitions and offerings is evidently working well; they have seen an influx of visitors since they officially reopened at the new location in September 2023. All in all, FMoPA is a worthy exhibition venue for SPMOP’s Photo Laureate.

Poetry and Photography

Ellis is not only a photographer but also a published poet and a bandleader. Since the beginning of his Photo Laureate journey, he has treated the community to bi-weekly photographic updates accompanied by his free-flowing poetry. Even more powerful when spoken out loud, they highlight Thomas´ creativity and provide a glimpse into his intriguing musings.

Combining two art forms can make it greater than the sum of its parts. For this reason, poetry and photography are a match made in heaven! This past May, Keep St. Pete Lit! held a Poetry Open Mic at St. Petersburg’s Studio@620, featuring a special photography edition of their poetry open mic to celebrate the month of photography. Local talent from all stages of life brought photographs that are dear to them and shared their poems, prose and spoken word. It was beautiful to see and experience people at their most vulnerable, sharing their most inner thoughts, all cheered on by a very respectful and supportive audience. Keep St. Pete Lit! plans to invite Thomas Sayers Ellis as a featured speaker in the near future.

Also this past May, SPMOP presented an exhibition titled Photo Laureate 2024: the Nominees at the Morean Arts center which featured the work of the following five local artists: Christa Joyner Moody, David Moreno, Jose Ramirez, Marian Tagliarino and Ric Savid. From this impressive grouping, the torch of Photo Laureate was passed on to Ric Savid, an amazingly skilled artist who shoots mostly in film and specializes in portrait photography.

We can all look forward to next year’s St. Petersburg Month of Photography celebration and a future public exhibition of Photo Laureate Ric Savid’s unique and exciting exploration.

About the author

Originally from the Netherlands, author Clara ten Berge has been living in Tampa for 2.5 years with her husband. In the Netherlands (Amsterdam), she worked at several museums. She has volunteered at FMoPA for a year, and is currently volunteering for SPMOP as Creative Director.

A special thank you goes out to the Gobioff Foundation for sponsoring the exhibition and to St. Petersburg Month of Photography’s entire team.