My Camera My Self(ie)

by Sabrina Hughes

In my History of Photography course, there is a class meeting on the syllabus dedicated to discussing selfies. I’m sure my undergraduate students roll their eyes when they see this and wait for me to deliver a punchline that never arrives. Discussing selfies, even uttering the word at all, feels like a relic of 2014, a simpler time. There can’t possibly be any more defenses or lamentations can there? Can’t we just stop talking about them?

Not quite yet. The exhibition This Is Not a Selfie: Photographic Self-Portraits from the Audrey and Sydney Irmas Collection, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg, Florida once again revives the conversation between the art of photographic self-portraiture and the omnipresent culture of the selfie.

The term selfie is cute. It’s a truncated form of self-portrait, just as the image produced is, presumably, dashed off quickly, without forethought, without composition, without art. The word, like the photo itself, and a characteristic projected onto people who take selfies, is infantilizing. Selfies are immature. They are not and will never be serious art. They are not worth talking about. SELF PORTRAITS, on the other hand, are demonstrative of the skill of the artist. They can be political, satirical, cutting. They can be ART. This artificial dichotomy permeates all critical discussions of selfies, and is the very cornerstone of the exhibition.

To anyone without a background in art, the title of the exhibition simply seems to reiterate that claim that selfies are somehow lesser than. But it asks us to grant these self-portraits the benefit of the doubt. Don’t worry, these aren’t selfies. They belong here.

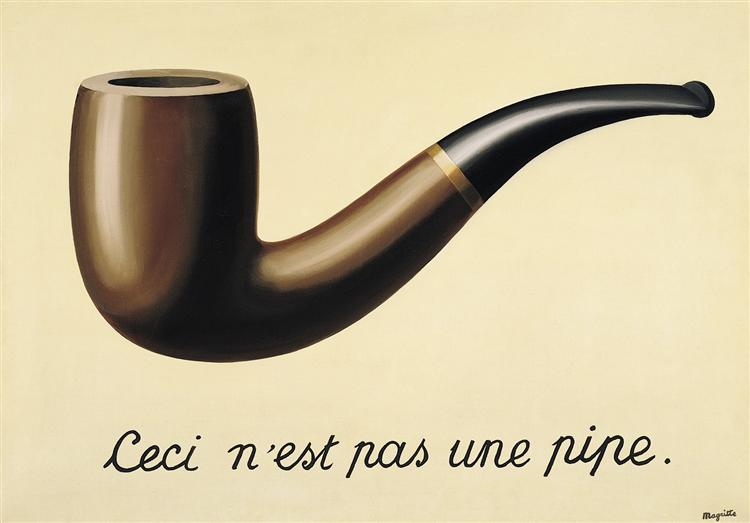

The title is a direct reference to Rene Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe) from 1928, also in LACMA’s permanent collection which may give some insight into the curatorial decision to reference this work in the title. The painting, which depicts a pipe floating on a flat ecru background with the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” inscribed in cursive script beneath plays with the ways meaning is ascribed to objects. This is not, in fact, a pipe. It is a painting.

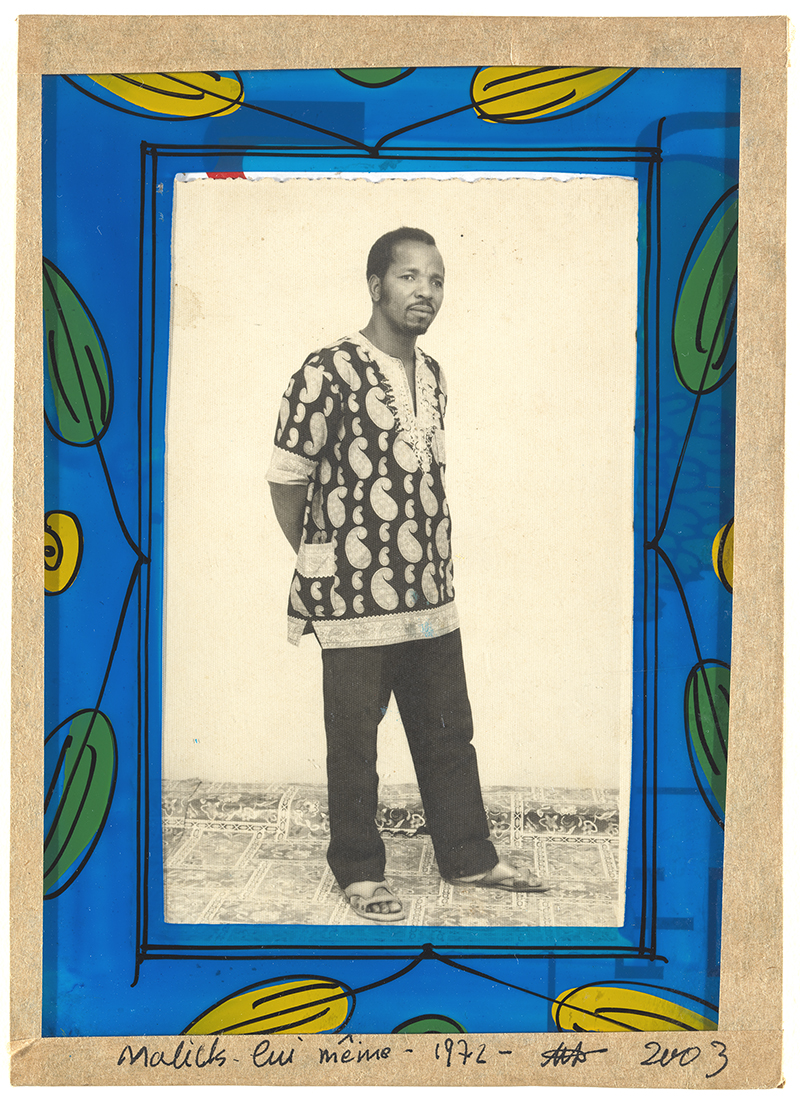

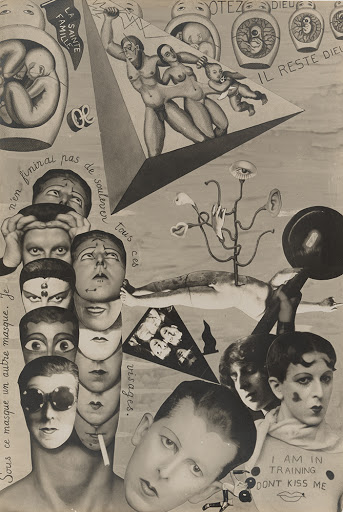

This is Not a Selfie contends that the photographic self-portraits within are not selfies. They have loftier aspirations and have Something To Say. They are role play (like Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #5 from 1977), they are explorations of identity (like Claude Cahun’s photocollage I.O.U. (Self-Pride) from 1929-30), they are political statements (like Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self Portrait from 1988, a clear commentary on the devastation caused by AIDS in the gay community). Self-portraits can be artificial (like Lucas Samaras Photo Transformation 8/19/76), they can be authentic (like Malick Sidibé’s head-to-toe Malick lui même from 1972), they can be deadly serious or playful (like William Wegman’s Half and Halfs from 1973). They can be anything. Except they can’t be selfies.

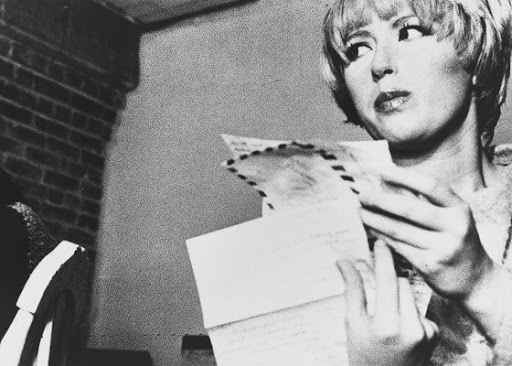

Certainly, a number of the photographs in the exhibition truly do not function within the art historical discourse of self-portraiture: they are not selfies. I think of Sherman’s Untitled Film Still series where she is very obviously not Cindy in front of the camera. She is an anonymous ingenue from a-movie-that-looks-familiar-but-you-can’t-quite-place-it. She is a fabrication. Likewise, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photo of his recumbent torso and legs framing a street scene, for instance, seems less about him as a subject and more like a playful riff on his skill at finding a decisive moment even while he’s resting.

In a number of the works, the photographers wear masks, turn their backs, or otherwise keep their face out of the camera’s sight. Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s Untitled from The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater (where everyone photographed for the project wears a rubber mask) confounds the viewer—it is hard to tell whether Meatyard also wears a mask or if his face is simply obscured in the shadow of his hat. Wolfgang Tillmans’ Lacanau-self (1986), a deadpan photo from the point of view of Tillmans’ eyes—what he would see as he’s looking down—may leave viewers asking what does or doesn’t make a self-portrait? Is it required that we see the artist’s face or any identifying characteristics at all? Lee Friedlander’s shadow reveals his proximity to a woman he follows on the street of New York City (1966), which is how his presence manifests in front of the camera while he remains safely behind it. Is a shadow a self-portrait? Shrug.

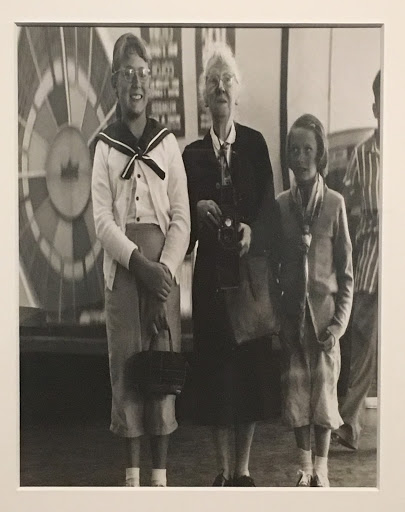

The real contradiction within the exhibition comes when the institution is left to perform the interpretive gymnastics of justifying how some of the images are different from selfies (spoiler: some aren’t any different! Does this invalidate them as art? No!). Photos by Imogen Cunningham (With grandchildren at the Fun House) and Ilse Bing (Self-Portrait in Mirrors) are no different in intent or execution than a mirror selfie that draws the ridicule of many on the internet for being vain or silly. Most poignant of the mirror selfies, and possibly of the entire exhibition, is Diane Arbus’s disarmingly intimate Self-portrait in mirror (1945) where the sometimes brutalizing photographer, pregnant with her first child, uses her full-length mirror and bulky view camera to create a gentle nude to send to her husband while he was overseas in the Army.

Berenice Abbott’s Portrait of the Author as a Young Woman is delightful, an analog distortion of her face to comic effect. One of my favorite images in the exhibition is 1001 Gesichter (1957) by Peter Keetman. Between Keetman’s face and the camera lens is a wet screen. His face beyond the screen is out of focus but thousands of tiny Keetmans are refracted in the water droplets suspended in the mesh and look back at us. Photographers experimenting with their photographic tools create playful images with water, mirrors, disco balls, and double- or long-exposures.

This is Not a Selfie invites us to consider the ways that, in the hands of artists, the self-portrait can be invested with any number of culturally important interpretations. I would invite a critical viewer to ask in response: why and how are selfies assumed to be devoid of these characteristics? What is the ideological difference between artists experimenting with mirror selfies and distortions, costumes, masks, or alternate selves and any one of us trying the same via our digital camera, facial recognition filters, and Instagram? Doesn’t the nearly ubiquitous access to cameras via our phones (which is what ushered in the explosion of selfies) encourage a new generation of photographers in this type of experimentation?

If I were discussing This is Not a Selfie with my History of Photography students, I would ask them to think carefully about what is at stake in the narrative of the exhibition. Before we discuss selfies in the course we have already spent two classes talking about how photography has functioned as a tool for marginalized groups, particularly in Jim Crow America. While, for example, African Americans were often portrayed in the popular media through a variety of insidious (and persistent) stereotypes, their personal photos of family and friends reveal the antithesis of that harmful view. We learn that photography has a unique ability to empower individuals and groups to conceive and represent the image that they, not others, want to show to the world. Photography is a powerful tool for self-fashioning. It’s within this context and with this groundwork that we finally approach the discussion of selfies as a product of other drives within the history of photography, the history of art, and the social history of photography in its most banal and everyday form: printed or digital personal albums. By the time the class comes around the students completely understand why selfies must be discussed.

The politics of self-representation cannot be overlooked and should not be dismissed. What is behind the pervasive urge to collectively disparage a form of self-representation that empowers the photographer-slash-subject in crafting and distributing their own image? Who is doing the disparaging and who benefits from the results? For instance, when Vogue, uncontested international arbiter of taste and high fashion, publishes an article calling selfies idiotic, readers are being told that they are not good enough as they are. It makes sense. Why should readers listen to Vogue (and therefore keep buying the magazines and the products from the magazine’s advertisers) if they started believing what their selfies tell them—that they are already enough?

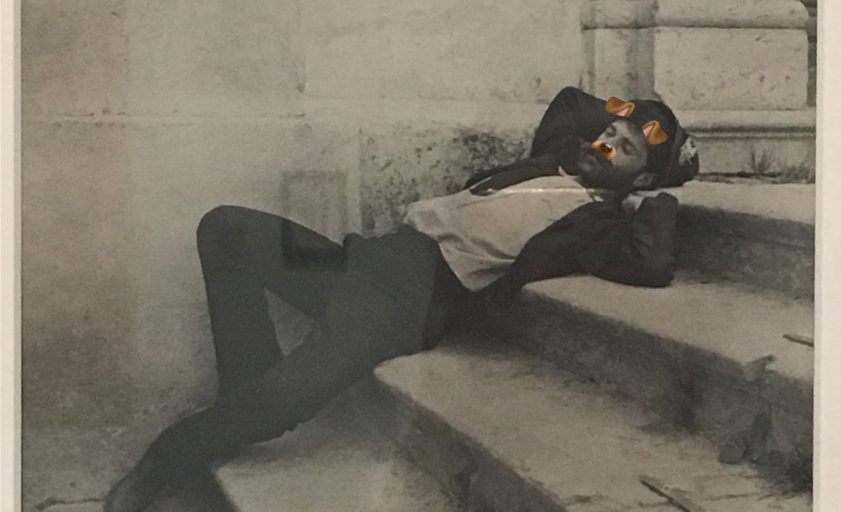

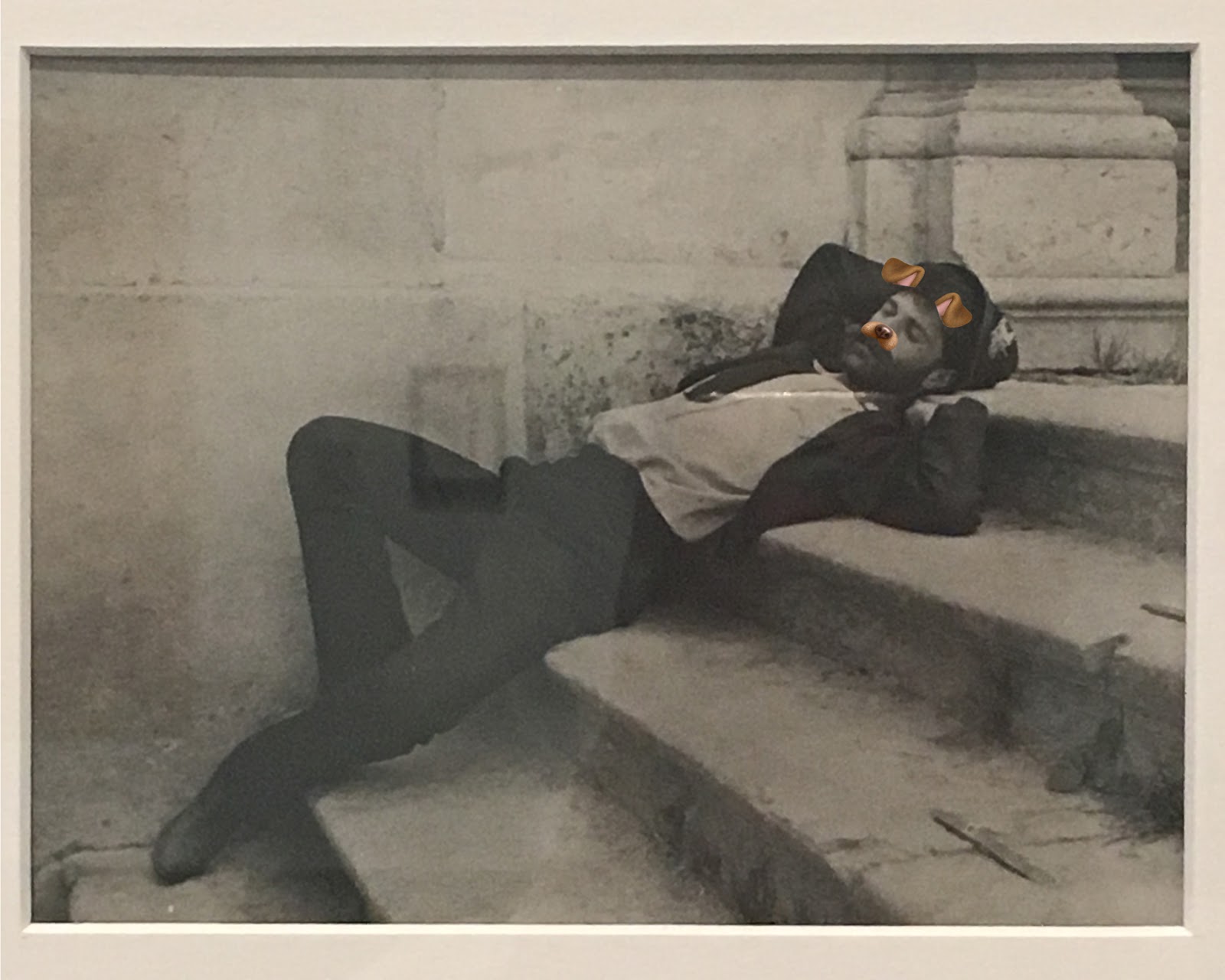

For museums—elite cultural institutions responsible for defining what is or is not high art while collectively struggling to diversify their collections and expand the voices they represent—punching down at selfies feels like a cheap shot. Why can Alfred Stieglitz languor on a set of picturesque steps and set up his self-timer but we should not? Why can artists document moods or changes in their bodies but we are wrong to? Why not use the institutional platform to stand up for and legitimize the lineage of selfies as an integral part of the history of photography (one of the earliest photographs after its invention, Hippolyte Bayard’s Self Portrait as a Drowned Man from 1840, is a selfie after all) instead of creating a narrative that tries to create differences in practice, intent, or validity when there often is none?

All of these questions invite one more: how should we view selfies if not as silly, vain, and disposable? Like any form of visual representation, selfies mean any number of things to each person who makes them. Just like the people that make selfies, they don’t have to hold to only one interpretation. Their ambiguity is their power. They mirror the depth and breadth of all of our various lives and experiences. For some of us, our very existence is political. Making ourselves visible as we want to be seen is a way to retain control of the means of representation rather than leaving it to those who want to control, influence, or sell to us. That is, in fact, how I define selfies to my classes. An image wherein the subject is also in control of the mode of representation. All selfies are political. We, and our selfies, contain multitudes. Take more selfies.

Bay Art Files contributor Sabrina Hughes holds an M.A. in Art History from the University of South Florida, with a focus on the History of Photography. Hughes has worked at the National Gallery of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg and is an adjunct instructor at USF and is the founder and principal of photoxo, a personal archiving service specializing in helping people preserve their family photos. She also has an ongoing curatorial project, Picurious, which invests abandoned slides with new life. Follow her on Instagram @sabrinahughes for selfies, hiking, and dogs, and @thepicurious for vintage photos.

Conversation with a Curator: Really! This is (So) Not a Selfie

Thursday, October 25, 2018, at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg.

FREE with Museum admission, $10 on Thursdays after 5 pm.

The special exhibition This is Not a Selfie is curated from a single collection, the Audrey and Sydney Irmas Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

This is Not a Selfie curator Eve Schillo, Assistant Curator of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department at LACMA, will be at the Museum on October 25th for a gallery talk to discuss the influence of the Audrey and Sydney Irmas Collection of self-portraiture photography in today’s world.