An exhibition review of Tom Jones: Here We Stand

by Sabrina Hughes

By turns witty, moving, and poignant, the exhibition Tom Jones: Here We Stand at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, makes a clear statement that Indigenous Nations remain connected to their past while ensuring their values are projected into the future. Tom Jones is a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin.

This is the first major retrospective of Jones’ career and features more than 100 photographic works in more than a dozen series. Tom Jones: Here We Stand originated at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend, Wisconsin. The exhibition was co-curated by Dr. Jane L. Aspinwall, Senior Curator of Photography at the MFA, and Graeme Reid, Director of Exhibitions at the Museum of Wisconsin Art.

Here We Stand showcases Jones’ photographic vision ranging from intimate shots inside his relatives’ homes, to acerbic wit recording appropriated Native names and iconography in the American landscape, to majestic and monumental portraits with hand-beaded embellishments.

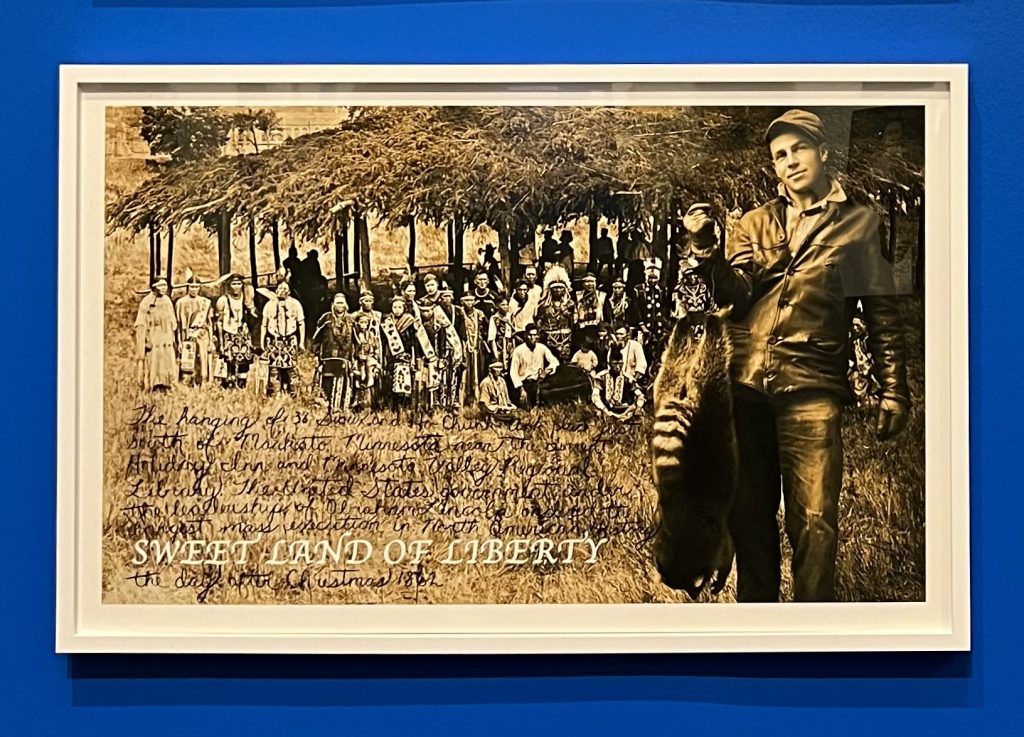

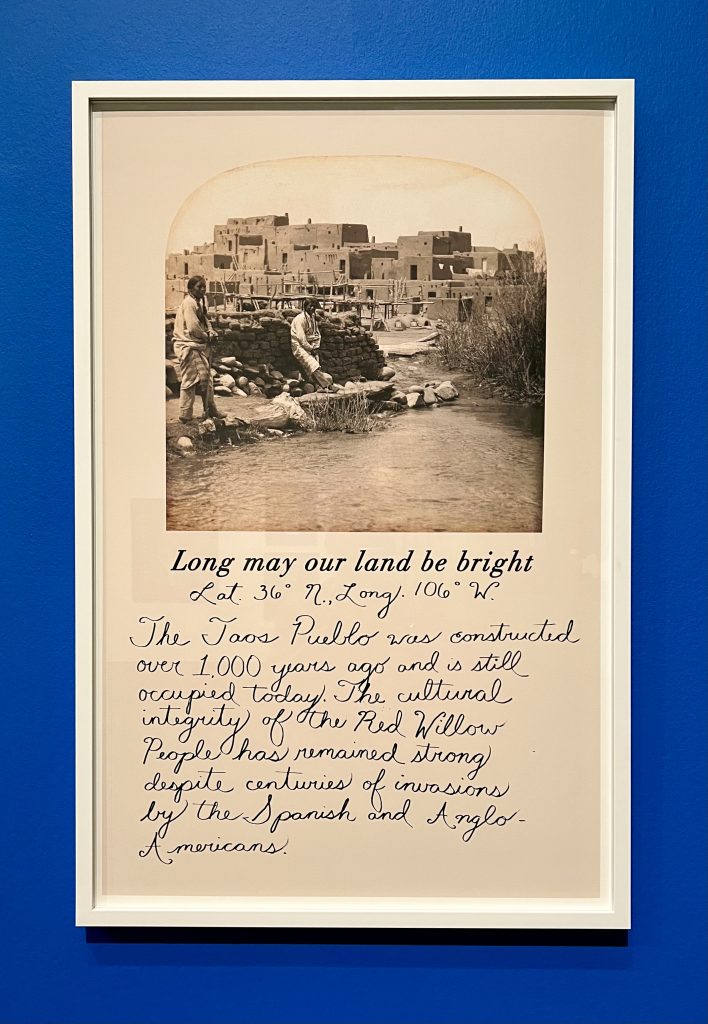

Jones’ early series Dear America pairs enlarged collaged historical vernacular photos with diegetic captions that force viewers to confront their assumptions about the Native history they may have learned.

On loan from the Artist. Image credit: Bay Art Files.

On loan from the Artist. Image credit: Bay Art Files.

In the image Sweet Land of Liberty, which collages a 19th-century group portrait of Sioux with a jaunty white hunter who has harvested a raccoon, Jones has written a short summary of the largest one-day mass execution in American history–when Abraham Lincoln approved death sentences for 38 Sioux men on December 26, 1862. Jones employs a similar technique with the image Long May Our Land Be Bright, half of a 19th-century stereographic image from Taos Pueblo. In this text inscription, however, Jones celebrates that the Red Willow People of Taos Pueblo have maintained their cultural integrity despite centuries of invasions by colonizers.

The beaded portraits in the Strong Unrelenting Spirits series build on the technique Jones used in Dear America, adding intricate beadwork to the large-scale portraits. Members of the Ho-Chunk nation pose in front of a stark black background, many in traditional ceremonial garb. These portraits are striking in their size as well as in the subjects’ appearance. What, in reproduction, appears to be designs drawn on the black background behind each individual is actually intricate beadwork applied to the surface of the photograph itself.

Even before European colonizers introduced colorful glass beads in trade, for centuries Indigenous artisans created beads from stones, bones, and shells, and used them to create jewelry and embellish clothing.

For Jones, the beadwork on these photographs represent a ritual encounter with ancestors. “Beading is a metaphor for our ancestors watching over us. I am also referencing an experience I had when I was about 8 or 9 years old. My mother took me to see a Sioux medicine man named Robert Stead. He led the call to the spirits, the women began to sing, and the ancestors appeared as orbs of light.” Strong Unrelenting Spirits eschews the formalism of photographic portraits that seek only to show what is before the camera. Combining the realism of photographic portraiture with the spiritual experience of light orbs further cements a Native visual language that can combine the visible and ethereal presences of one’s experience.

On loan from the Artist. Image credit: Museum of Wisconsin Art.

A recurring theme in Jones’ work is the appropriation and commodification of Native culture in America. Two series, The North American Landscape and I am an Indian First and an Artist Second, use plastic figures from Cowboys and Indians playsets to wryly reference the way Native culture has been repackaged and sold as a product. The images in the series “Native” Commodity are deadpan documentary representations of Indigenous culture co-opted by the tourism industry. The series Studies in Cultural Appropriation also presents a witty question: if Native designs are readily appropriated by corporations, why not make use of a variety of Indigenous material designs for high fashion?

On loan from the Artist. Image credit: Bay Art Files.

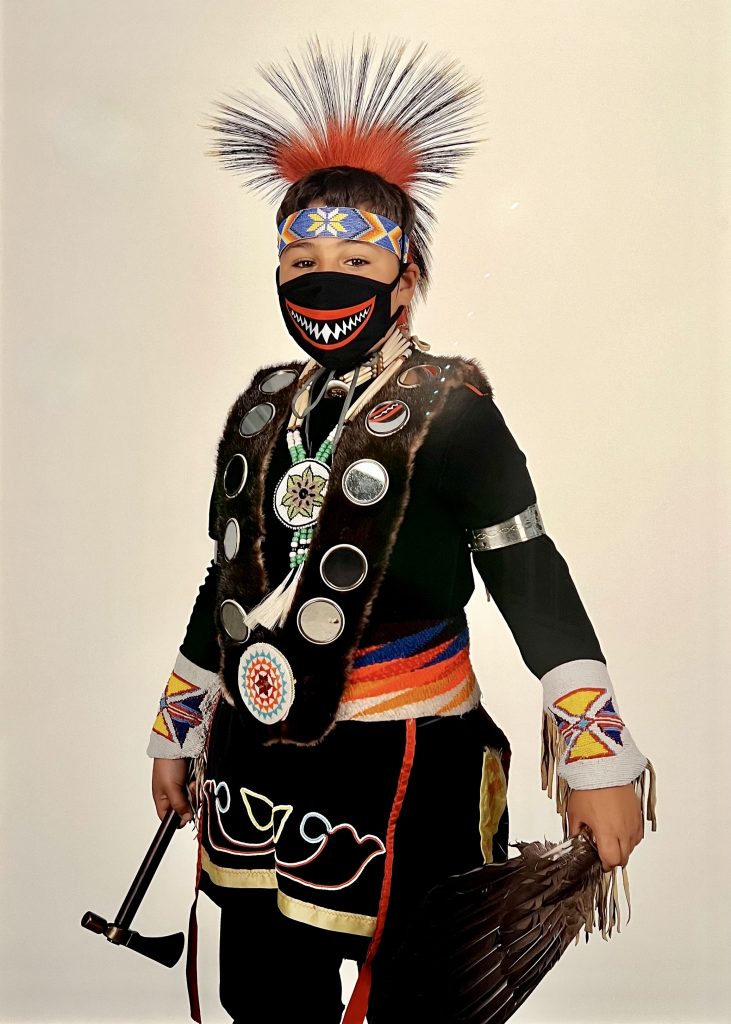

One of the most striking photographs in the exhibition is a portrait of Blake Funmaker (2020) in ceremonial regalia that includes an embroidered and beaded face mask. COVID-19 was a particular danger to Native American communities. Noreen Goldman, demographer and social epidemiologist at Princeton University reports, “Elevated COVID-19 death rates among Native Americans serve as a stark reminder of the legacies of historical mistreatment and the continued failure of governments to meet basic needs of this population.” To promote the protection of the community during the pandemic, the Ho-Chunk Nation Department of Health commissioned Jones to photograph members of his community with facemasks as part of their full regalia.

What is consistent across the diverse bodies of work is the existence of a Native photographic language, one that blends traditional Indigenous art forms imbued with ritual, spirituality, and heritage with the detail and historicity lent to a subject by the medium of photography. In contrast to white photographers who have perpetuated the idea that Indigenous nations have vanished or are frozen in a romanticized past, Jones’ visual language instead reinforces that Native peoples are resisting erasure and maintaining their identities despite attempts by colonizers to assimilate them.

Tom Jones: Here We Stand is on view at the Museum of Fine Art, St.Petersburg through August 27, 2023. The exhibition originated at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend, Wisconsin. A catalogue, including a major essay by Dr. Jane L. Aspinwall, accompanies the exhibition and is available for purchase in the MFA Store. Installation photography photo credit: Darcy Schuller, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg.

About the artist

Tom Jones is an artist, curator, writer, and educator. He graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a Master of Fine Arts in Photography, and a Master of Arts in Museum Studies from Columbia College in Chicago, Illinois. Jones is currently a Professor of Photography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. For more information about the artist, visit his website.

About the author

Bay Art Files contributor Sabrina Hughes holds an M.A. in Art History from the University of South Florida with a focus on the History of Photography. Hughes has worked at the National Gallery of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, and is an adjunct instructor at USF, and is the founder and principal of photoxo, a personal archiving service specializing in helping people preserve their family photos. She has an ongoing curatorial project, Picurious, which invests abandoned slides with new life. Follow her on Instagram @sabrinahughes for selfies, hiking, and dogs, and @thepicurious for vintage photos.