By Selina Román

I have a couple versions of a recurring dream. In one, a car I am driving careens off the road into some unknown body of water – sometimes clear, sometimes murky. Sitting in the driver’s seat I become a spectator as water seeps into the car and it slowly sinks away from the world above. In the other version, I’m driving down an old Florida backroad surrounded by swamp. As I turn a corner, the road disappears beneath water that has breached its banks. I recall in this dream that I felt scared but mostly hopeless. In all of my drowning/sinking dreams, I wake up never knowing if I made it or not.

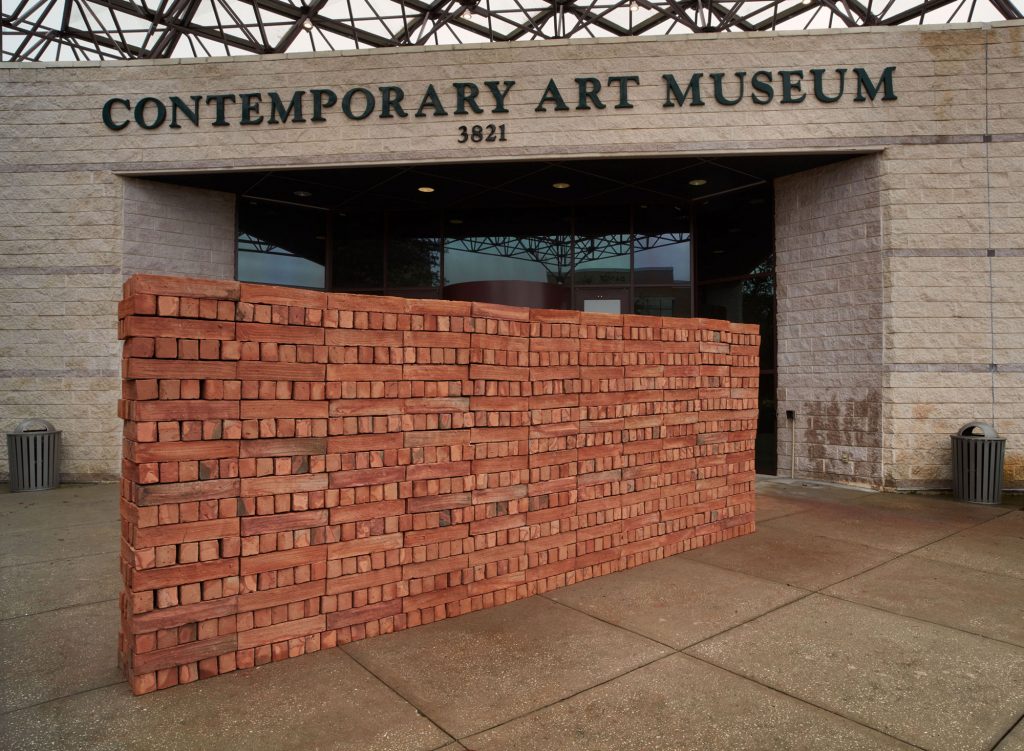

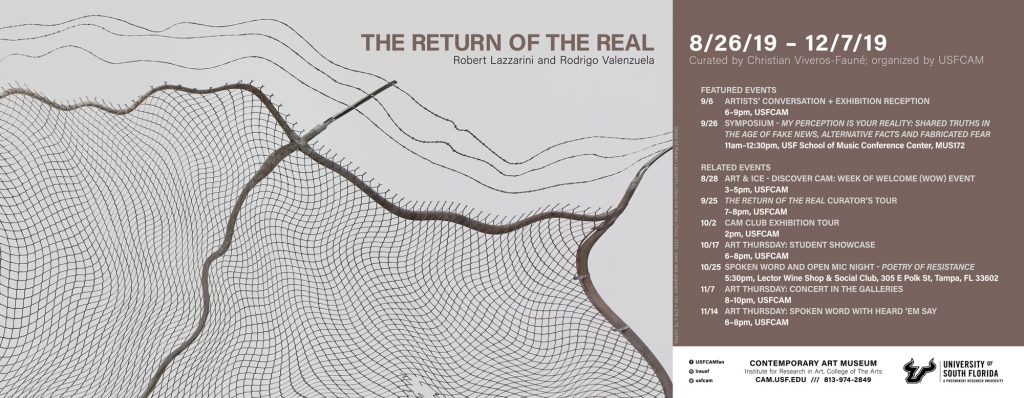

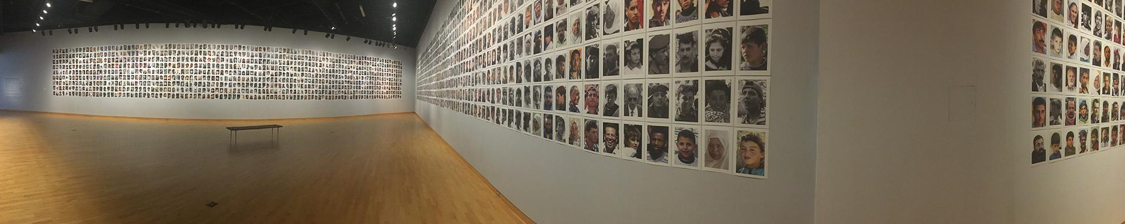

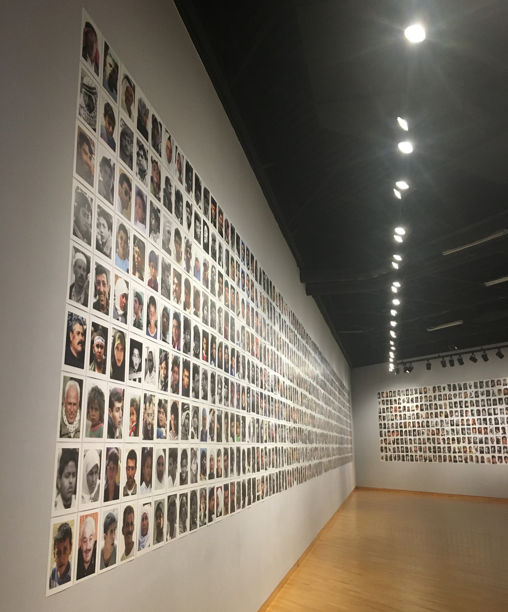

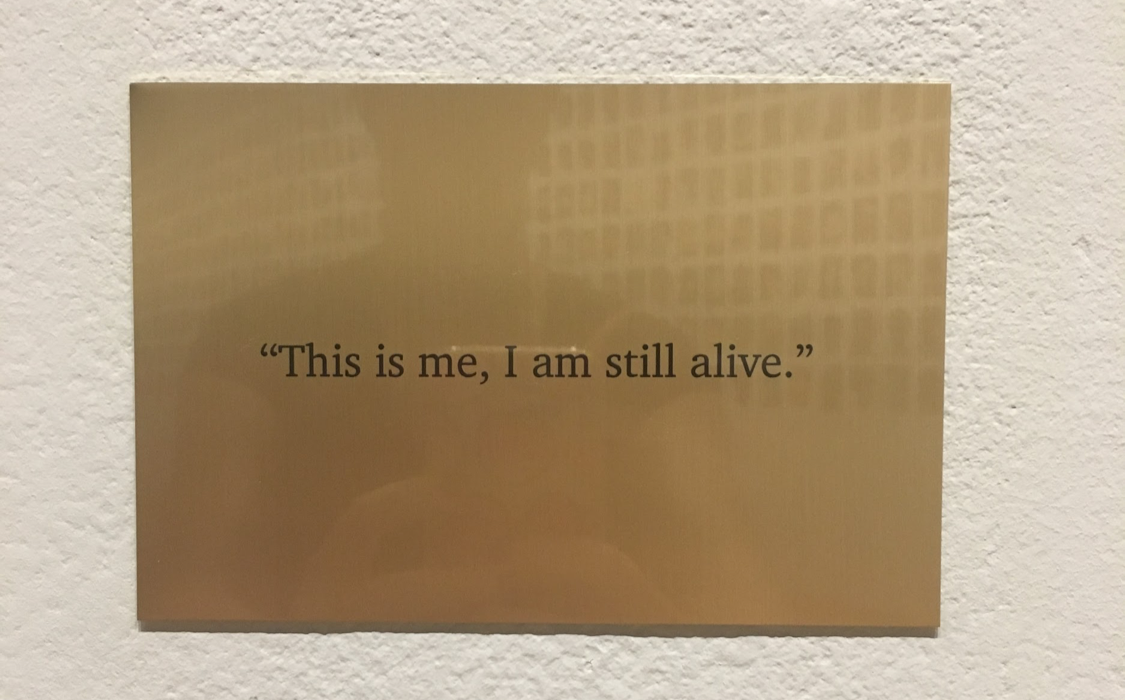

That sinking feeling rushed back as I took in the large-scale photographs in the exhibition FloodZone, by Miami-based artist Anastasia Samoylova on view in the University of South Florida’s Contemporary Art Museum. The lush images, full of color and water, are akin to walking through a waking dream where the surroundings are familiar but something always feels amiss. Her photographs, just like the intrusive water she depicts, seep into the psyche and linger.

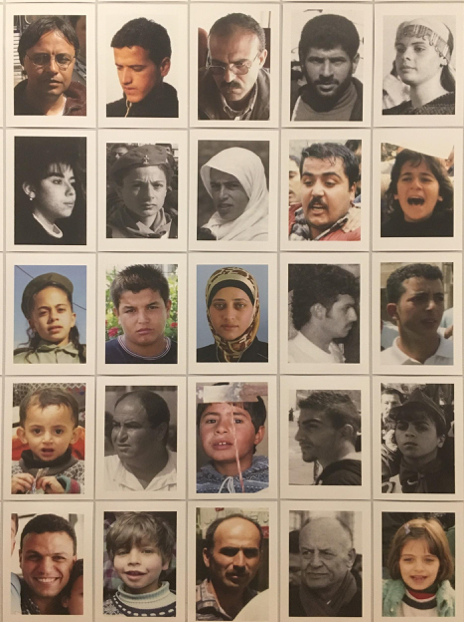

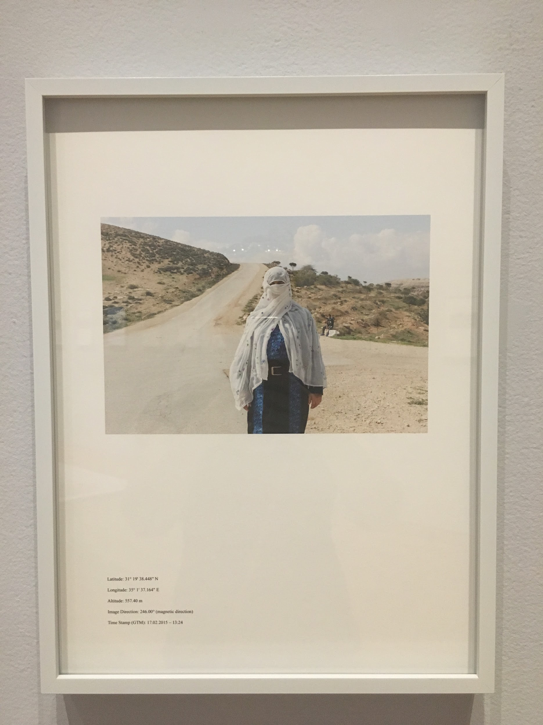

As Samoylova pointed out in a recent artist talk, nowhere in the images will the viewer see the catastrophic. Those fraught scenes are relegated to the news. In her photographs, it’s flooded streets after a typical rainstorm, swollen waterways, construction sites, and mysterious figures navigating a landscape in limbo. However, the most telling images are the ones of details – ones that most people overlook. In these, nature fights back and it just may be winning.

I lived in Miami for nearly six years in the late 2000s. Cranes punctuated the skyline for projects with names like Quantum, Paramount, Epic and Infinity – names that embodied the human need to go higher, achieve more, get more. I see this quest again in Samoylova’s images of architectural renderings – computer-generated images showing happy couples sharing a romantic moment poolside or the luxe interior of a living room. But look a little longer, past the promise to the reality and see the abandoned construction site, detritus spilling over the sign like weeds. In what seems to be a nod to the developers’ slick signage, these stand-alone images occupy the gallery floor confronting viewers in their own space. It’s here in the intersection of reality and façade, of man versus nature, that Samoylova’s photographs become a poignant harbinger.

Just like the signs for the construction projects, Miami puts on a good face for tourists, especially those that don’t have to leave the beach save for going to and from the airport. I learned this when I was living in Little Haiti in 2005. I had just moved to Miami and was welcomed that year by hurricanes Dennis, Katrina and Wilma. That year, the Atlantic was the hottest on record and spawned more than a dozen named storms. While Dennis and Katrina caused damage and power outages in South Florida, Wilma delivered a staggering blow to an already storm-fatigued area. My roommate and I rode out the storm as winds howled. From my apartment window, I watched an electrical transformer explode, in awe of the green flashes of light.

Little Haiti was without power for four weeks, while just across the railroad tracks that line Dixie Highway, lights flickered back on and air conditioners were humming in a matter of days. A coworker bemoaned that she was without power for about 45 minutes – she lived in an area of the beach, near hotels, where the power lines were buried. That year of storms awakened me to the social implications of climate change.

As a Miami Beach resident, Samoylova sees beyond that touristy façade. Some of her most successful images are those of the details that only someone living there would notice. On the side of a concrete overpass pylon, a green plant fights its way out of a crevice while brilliant violet mold flourishes beneath it. Severe lines and geometry dominate the visual plane but the plant and mold triumphantly stand out from the stark environment. It’s repulsive and beautiful in the same breath. In one of her few black and white photographs, a small, proud plant grows near the roof of a building, its roots clinging to the surface like veins and capillaries. Air plants are common in Miami, but there’s something different about this one: the plant’s roots have been painted the same white as the building. In these moments, I find myself hopeful and terrified as nature asserts herself.

Samoylova does not shake her finger at you. She’s not passing judgment. If anything, she collectively takes our heads and turns them, telling us to look closely at these pieces of a puzzle she’s assembled. As singles, they are strong images but together, they become this dull pang in the pit of my stomach – the knowledge of what’s at stake.

In one particular photograph, fourteen eggs occupy a nest tucked between concrete and steel adjacent to an unidentifiable body of water. The carefully composed image of the nest and water is a perfect inverse of each. But this ying-yang, however perfectly arranged in the frame, belies the precarious balance of the natural world against the man-made. The eggs appear protected, but from above they are not. Will they hatch? Or maybe the larger question is will they survive once they hatch? Will we make it? It’s this false sense of security that plagues South Florida.

When looking at her work, I am struck and reminded of Robert Frank’s The Americans. In the 1950s the Swiss-born Frank traversed the country making documentary photos of post-war America. With a keen outsider’s perspective, Frank’s images revealed not a prosperous super power, but a country marred by racism, poverty and injustice. Samoylova, born and raised in Russia and living in Miami since 2016, also has that eye for detail and incongruity. Just like Frank’s, her images show us that there is more to learn if we just look a little longer and a little harder.

In an homage to Miami’s color, Samoylova designed the eye-catching presentation of the exhibition that underscores the thin line we Floridians tread. Angled swathes of bright colors on the wall – sky blue, canary yellow, magenta – serve as a backdrop for the works. The colors are painted on a diagonal and border a deep gray. Standing in the gallery, the sloped lines create a sense of uneasiness and symbolically represent the downhill direction in which we find ourselves. Yet look again and those same lines could be the uptick of hope.

From the Everglades to South Beach, humans have invaded this place, not only altering the landscape but upsetting its delicate ecological balance. Her compositions show the constant battle between man and nature. The brilliance of so many of the images is they’re composed in a way in which it’s difficult to determine who is dominating who. In an image of Miami’s famed Vizcaya mansion, water covers the intricate inlaid marble floor of its elaborate latticed gazebo with Biscayne Bay ominously visible through its arches. The horizon all but disappears under the overcast day, and the bay and the floor are one in the same. The breach is not catastrophic in the moment the photograph was made, but the potential for disaster is made clear.

Several years ago, I sat in Miami’s Legion Park which overlooks Biscayne Bay. The breeze rustled the palms, which stood majestically and stoically against the sparkling blue water. It was nothing special in particular – just Miami on a good day. I snapped a photo, but it’s what I wrote under the image later that still haunts me: “I belong here.” But now I’m not so sure any of us do.

Just the other night that recurring water dream came rushing back. This time I was visiting friends in their beachside condo. As I walked to the balcony, I could see the waves of the rising ocean swirling outside. When I looked down, however, I realized there was no beach below and that the ocean was lapping at the building not far from where I stood. That hopeless feeling also resurfaced. I woke up and my thoughts volleyed to Samoylova who offers us a slice of hope wrapped up in a wake-up call – a black and white photograph of her son, standing in ankle-deep water, surveying flooding in a parking garage. Will we let him and his generation inherit this flooded world?

This quiet, yet powerful and important show reminds us that Florida’s future is at stake as climate change and continued unchecked development wreck havoc. I am also reminded of what sadly could become Miami’s unofficial theme song, “Dear Miami” by Irish singer Róisín Murphy: “With a little style fool ‘em for a while, but you can’t turn back time,” she sings. “Dear Miami, You’re the first to go, disappearing under melting snow…”

Selina Román is a Tampa-based artist and photography professor. She received her Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of South Florida.

FloodZone is on view at the USF Contemporary Art Museum on the campus of the University of South Florida in Tampa through March 7th. The exhibit was curated by Sarah Howard, organized by USFCAM, and supported in part by an Oolite Arts grant, a grant from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and Dr. Allen Root.

Sponge Exchange, in the adjacent Lee and Victor Leavengood Gallery presents artist Hope Ginsburg’s new collaboratively-produced video and sculpture installations reflecting on historic sponge diving and contemporary coral restoration and inspired by explorations of climate crisis impact on coastal ecosystems. The exhibition, also on view through March 7th, was curated by Sarah Howard, organized by USFCAM, and supported by a National Endowment for the Arts Art Works grant, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Dr. Allen Root, and the USFCAM ACE Fund.

Related event:

Art Thursday’s gallery talk and reception with artist Anastasia Samoylova and Ksenia Nouril, Ph.D., Jensen Bryan Curator, The Print Center, will contextualize Samoylova’s work within the historical and contemporary role of photography in society. Light refreshments will be served. Free and open to the public.