Faces in the Crowd

By Sabrina Hughes

Miki Kratsman’s exhibition People I Met at the University of South Florida’s Contemporary Art Museum (USFCAM) is a challenging exhibition, but maybe not for the reasons you would think. Though it deals with the emotionally and politically charged subject matter of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the subject matter itself is blunt and direct, a presentation of visual facts. Miki Kratsman: People I Met doesn’t ask viewers to do much more than to look, and continue to look, even if it makes us uncomfortable.

Kratsman is an Argentinian-born Israeli photographer who began his career as a photojournalist before he began to exhibit in an artistic context. The photographs in the exhibition borrow the aesthetics and content of journalism but subtly transcend the strict ethics of non-interference that is the photojournalist’s code. One senses the presence of Kratsman’s own compassion to create work inviting viewers to take a prolonged look at faces and places that may be otherwise easily passed over with a glance.

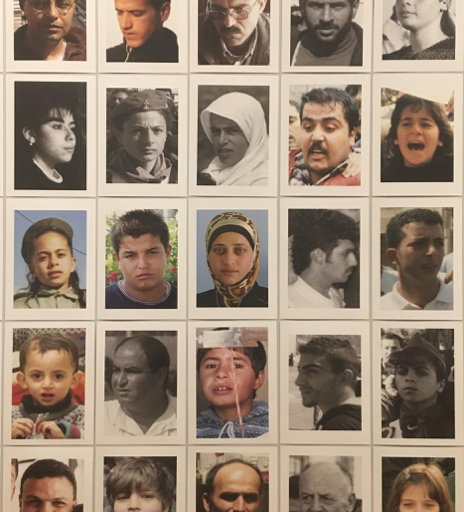

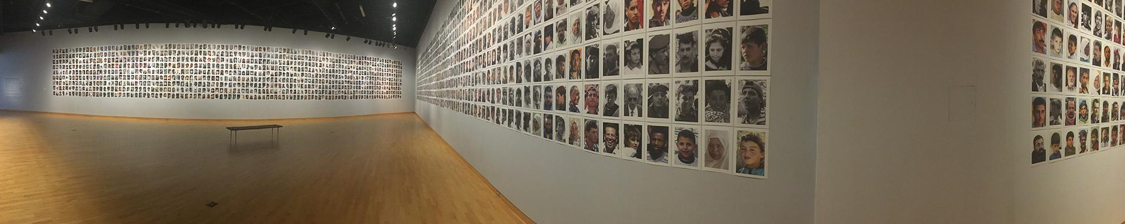

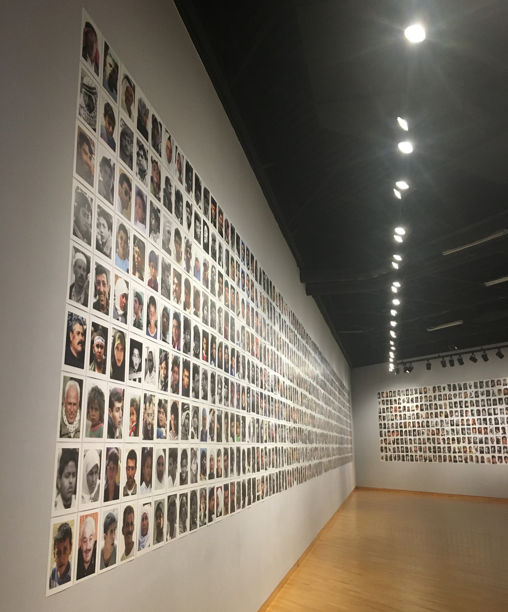

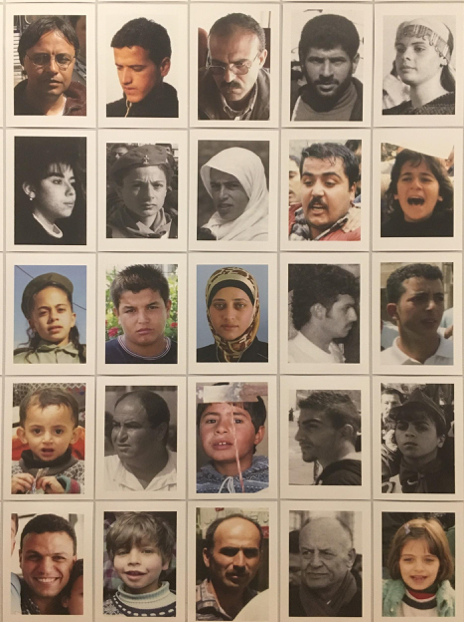

The dominant work in the USFCAM galleries is the project that gives the exhibition its name. The installation People I Met in the Lee and Victor Leavengood Gallery is an ongoing (2010-2018) collaboration between Kratsman and the Palestinian individuals who have borne witness to and participated in the decades-long conflict. Two-thousand grainy portraits fill three gallery walls, a scale that is challenging to describe and overwhelming to experience. Some people are looking straight at the camera and some gaze elsewhere. Kratsman’s source images are his own photographs from his career as a photojournalist, from 1993 to 2012. He delves into his archives to look behind the central subject matter and to create new images that isolate the faces of the countless bystanders.

The photos, and especially some of the expressions on the people’s faces, make me wonder what was happening in the foreground of the photos these were excerpted from. What are they witnessing–what is making them smile or shout? And to speak more broadly to their original context, what or who are we overlooking in the background of the billions of images that have already been made? Whose daily routines brought them into the path of some newsworthy event, and therefore into the frame of the photojournalist present to document it? What photos are you in, unknowingly? Who were you then and are you different now? Most importantly, who is interested in what happened to you after the shutter clicked?

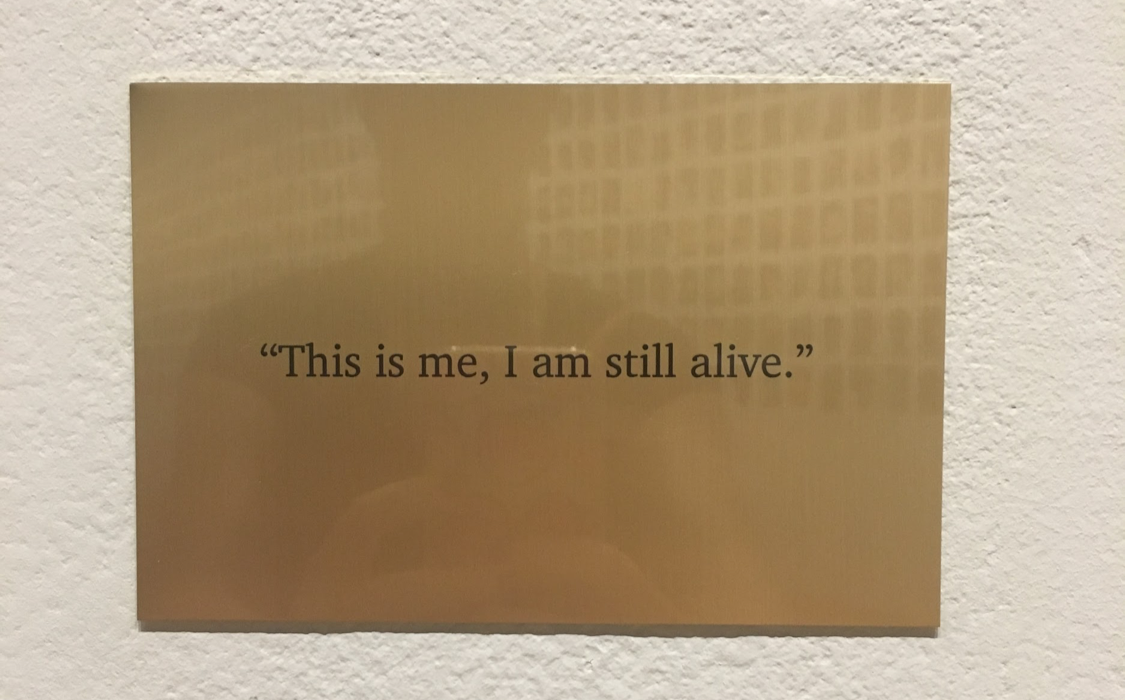

The photos are not only intended to be seen on gallery walls, in fact, they were first disseminated digitally. Kratsman posts the excerpted portraits to a Facebook Page dedicated to the project. More than twenty-thousand followers of the page see the images and comment on the photos of people they know, people they knew, or sometimes photos they recognize as themselves. Kratsman is literally picking faces from the crowds dispersed years ago and crowdsourcing the reply to the question “Do you know who this person is and what is his condition right now?” In the exhibition, some of these responses from the Page’s followers have been engraved on brass plaques. “My teacher, he was in prison but now he is out.” “He was the best man in Jordan Valley. Now he is dead.”

The plaques are in conversation with the photographs but exist at a physical and interpretive remove from the anonymous portraits. We don’t know to whom the plaques refer. If any of the 2,000 individuals pictured in this iteration of People I Met have been identified, are dead or alive, or of unknown status, we viewers do not know. We are invited to consider the text and the image separately and perhaps to imagine more about the relationship between the sea of faces and the comparatively few who have been recognized and whose status is known.

Kratsman’s People I Met runs counter to the emotional distance photojournalists must cultivate in order to do their job. Photojournalists often face criticism for taking a picture of a heinous scene rather than trying to help the people they photograph. Kratsman’s project of attempting to follow the thread of each individual’s life forward from when their paths crossed, always asking if they are in good health when a Facebook follower recognizes a friend or family member is a heartening gesture.

If the installation People I Met magnifies the sense of scale by isolating so many individual faces each affected by the conflict, the video 70 Meters… White T-Shirt (2017) does the opposite and compresses the impact. The video is a montage of every weapon discharge in the small village of Nabi Salih over the course of one year. After the sound of every gunshot, a rapid cut to the sound of another gunshot. We don’t always see where the shot is coming from and thankfully we never see anyone hit by a bullet. Watching the video, it all seems too brief. The shots come quickly and without reprieve (literally rapid-fire) but the acceleration of all of these incidents into the span of fewer than nine minutes seems to reduce the impact that these violent engagements have on the residents of the town. A shot that may change a life irrevocably is decontextualized and shortened to the length of time that the sound reverberates on the video.

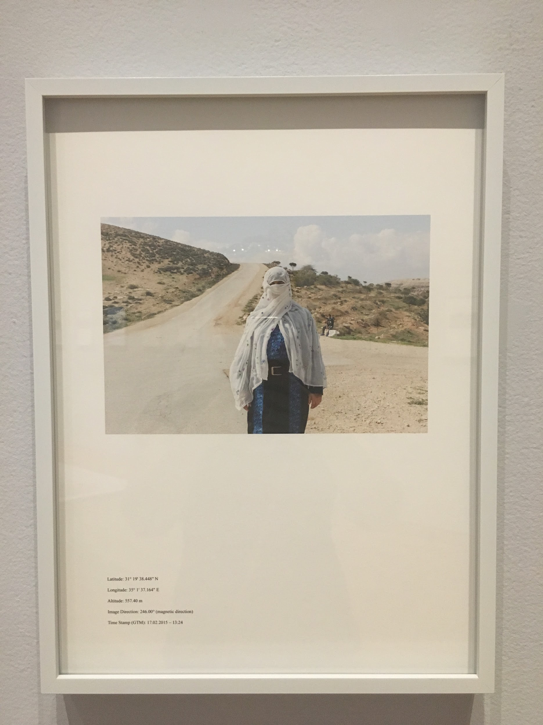

Displaced (2010) and Bedouin Archive (2015-2016), the other two projects in the exhibition document Bedouin life in the Negev desert and towns that are targeted for demolition. In Bedouin Archive, photographs of individuals and buildings in various states of demolition are identified only with the latitude, longitude, altitude, image direction, and time stamp. A document in the truest sense to record where Kratsman was and when, and what was in front of his camera at that moment. If the villages are demolished and people scattered, these photographs serve as a map of sorts to locate the inhabitants in a time and place that may be lost.

One of photography’s unique qualities in relation to other art media is its indexicality. Most photography operates on the principle that what the viewer sees on the print was at one time in front of the camera. Indexicality is photography’s mirror-like characteristic that most of us now take for granted; that which makes it possible to see photography as a presentation of facts, of truth. The person we see in the photo stood in front of the camera if only for a fraction of a second. These people were here. Some still are. I know that person, she is well. This building stood here at this time. This is what the village looked like. These are the sounds residents experienced regularly.

Once an artwork is released from the protected insularity of the artist’s studio into the world, the artist can no longer control its interpretation. Every individual who looks at a work brings her own subjective viewpoint and beliefs to bear. Remarkable in Kratsman’s work is his retention of a documentary viewpoint while treating such highly emotional and potentially polarizing subject matter. One does not engage in light discourse about Israeli-Palestinian relations. By its very nature, this body of work, in particular, has the potential to be highly polarizing. Yet, when in the gallery space, the exhibition seems instead to function as a document of life in this historical moment.

Kratsman’s photographs and videos open a space for questioning the monolithic perception of both Israeli and Palestinian identities and instead to think about the subjectivity of each person, photographer and photographed, as a sum of their experiences extending forward and backward in time from the split second recorded in the photograph.

Bay Art Files contributor Sabrina Hughes holds an M.A. in Art History from the University of South Florida, with a focus on the History of Photography. Hughes has worked at the National Gallery of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg and is an adjunct instructor at USF and is the founder and principal of photoxo, a personal archiving service specializing in helping people preserve their family photos. She also has an ongoing curatorial project, Picurious, which invests abandoned slides with new life. Follow her on Instagram @sabrinahughes for selfies, hiking, and dogs, and @thepicurious for vintage photos.

Miki Kratsman: People I Met is the first solo exhibition of this award-winning Israeli conceptual photographer to be presented in the United States and is on view at USFCAM through Saturday, December 8. It is the first exhibition organized by USFCAM’s newly appointed Curator-at-Large Christian Viveros-Fauné. A highly regarded international art critic and curator, Viveros-Fauné has also been named the 2018-2019 Kennedy Family Visiting Scholar at the USF School of Art and Art History.

RELATED EVENT: Film on the Lawn

Friday, November 16, 2018

6 PM

Free and open to the public.

USFCAM presents the award-winning documentary 5 Broken Cameras as part of their outdoor Film on the Lawn series. A first-hand account of non-violent resistance in the West Bank village of Bil’in, documented over a span of many years by Palestinian farmer Emad Burnat and then edited and co-directed by Israeli Guy Davidi, the documentary has been hailed as an important work of both cinematic and political activism. For more information about this free event, visit the Museum’s Facebook Event Page.