@tampabaebae art files

by James Cartwright

Jenal Dolson is a nervous flyer even under normal circumstances. Add scrambling to get out of the country during a global pandemic before international borders close and anyone’s stress levels will ascend to new heights. It is Tuesday, March 31st, and she is leaving the United States and returning home to Canada to shelter with her family as the severity of COVID-19 slowly dawns on U.S. citizens. She sits alone in Tampa International Airport, waiting to board a flight that she never expected to be on and saying goodbye to a place she is not ready to leave behind.

To call the last few weeks of Dolson’s time in Tampa a whirlwind would be an understatement. At this point in March, she is a MFA candidate at the University of South Florida, in the thick of her final semester when the coronavirus hits America. Between transitioning her in-person classes to an online platform (no easy feat for studio art courses), finishing her thesis work, writing about said work, preparing for install, and making travel arrangements, change is the constant. Her graduating class’s MFA exhibition Battin’ A Hundred is canceled, their reception is canceled, their panel discussion moderated by artist Kalup Linzy is canceled. It feels like everything is canceled. However, the artists are undeterred, and they still exhibit their work in the USF Contemporary Art Museum. There is almost a defiant pride in displaying their art knowing that it will not be seen in person.

Dolson spends her precious final hours in Tampa packing for her flight and installing her work in the CAM, with the invaluable assistance of museum staff Vincent Kral, Eric Jonas, and Tony Wong Palms. She recalls visiting the museum for the first time on a 2014 trip to Tampa and sensing then that she would one day show work in this space, a premonition fulfilled these six years later.

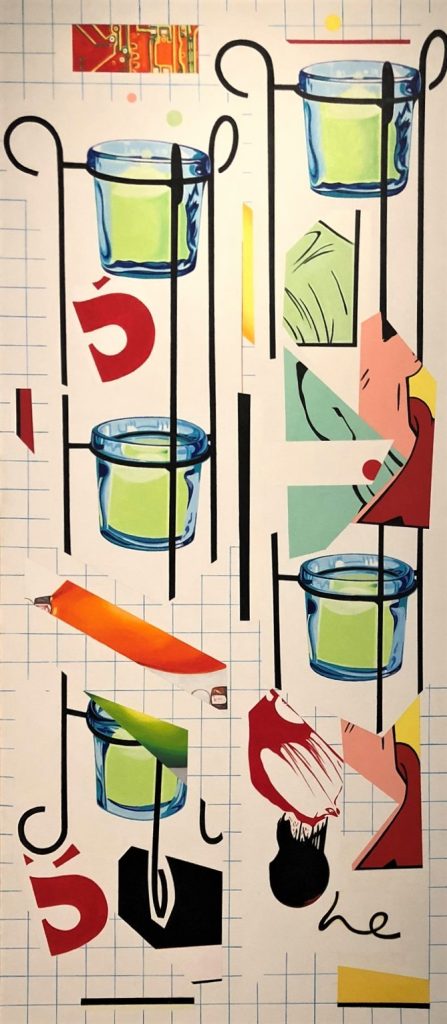

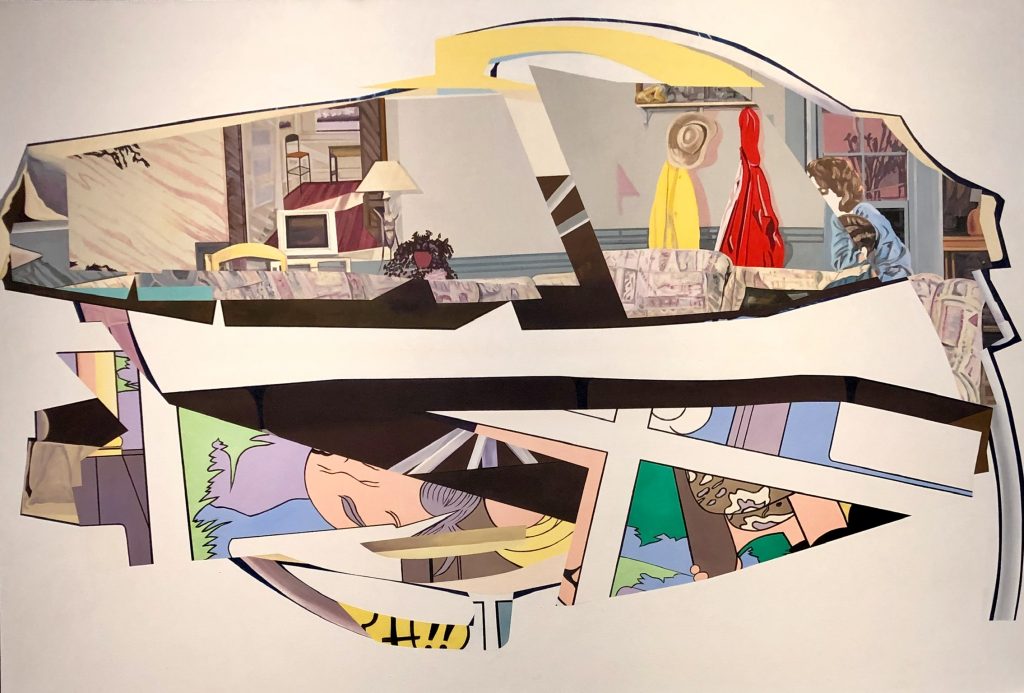

From the MFA thesis exhibition. Image taken by Jezabeth Roca Gonzalez.

From the MFA thesis exhibition. Image taken by Jezabeth Roca Gonzalez.

From the MFA thesis exhibition. Image taken by Jezabeth Roca Gonzalez.

Her arrival in Toronto is not met with a warm embrace from Dolson’s parents, who are relieved to see their daughter home safe but still respecting the social distancing rules that now measure our lives. Everyone dons their face masks and Dolson sits in her parents’ backseat on the car ride from the Toronto airport to their family home outside of Cambridge, Ontario, taking these moments to let a wave of quiet calm wash over her and finally exhale. She is deeply grateful to her parents for hosting her, knowing that in doing so they have committed to the country’s mandatory 14 day returning traveler quarantine alongside her.

Dolson uses the next few days to reacclimate to these surroundings, the familiarity of place comforting her during an unfamiliar time. She self-isolates in a section of her family’s basement, with her beloved chihuahua Bam Bam to keep her company and a mini-fridge stocked with snacks to keep her fed, courtesy of mom. That Friday she joins a Zoom reception hosted by CAM for the MFA exhibition, which has a great turnout as many people are eager to see the artists’ work and congratulate them. Dolson later passes the two-week quarantine mark on the same day that she passes her thesis defense, and her reward for this tremendous accomplishment is finally being able to hug her parents.

A welcome focus for Dolson’s energy comes in the form of creating a solo exhibition entitled Into the Belly for Tempus Projects, highlighted on the non-profit gallery’s Instagram account. The show, which ran from May 30th-June 12th, neatly aligns with the Tampa-based gallery’s approach to the pandemic’s unique challenges. Tempus is utilizing social media to showcase a series of mini-virtual exhibits that feature works on a small, intimate scale. As Tempus Founder and Programming Director Tracy Midulla explains, “We have taken the approach of offering small, short virtual exhibitions. This allows us to keep the quality of the work featured at a high standard, but the format and delivery of the works to a manageable level for everyone as we are distanced from one another.”

Into the Belly consists of eight coloured pencil drawings on gessoed board, with each work’s dimensions around 5×6 or 7×8 inches. Dolson’s process is reliant on found materials, so she seamlessly adapts to her new circumstances by repurposing leftovers in her old studio in her parents’ house. Her use of coloured pencils on board allows for textures to come out of the surface itself, some areas pulling through the grain of the wood or underlaying brushwork; paired with a uniform attention to colour blocking and gradient fades. These underlaying patterns resemble countless tiny fissures, which further emphasize the material’s surface while adding layers of complexity to already rich compositions.

The small scale of each work is in keeping with the gallery’s current theme of miniature exhibitions. Dolson also expresses her interest in scaling down the works to a size that is accessible, where they can be held in your hand and you can take them with you very easily. Although these new images are much smaller than her thesis paintings, she draws several parallels between the two bodies of work. Dolson clarifies that the viewer is still looking at a series of shapes, forms, lines, directions, and pathways, which you can follow around the work finding little areas where something new can be seen.

There is plenty to see in Dolson’s drawings, so much that you might get lost in looking. The artist presents the viewer with a plethora of shapes and motifs to latch onto and alluring pathways through each labyrinth. One might glance at a piece like Bathhouse and seize upon the chain in the lower right of the composition as a good entry point. If you follow this chain directly upwards, it becomes veiled by a light blue rectangular shape that hints of cloth or drapery. If you choose a different approach and start from top to bottom, does the chain then become unveiled? Other areas may suggest something recognizable while leaving you grasping to articulate this familiarity.

Into the Belly is an apt title, as Dolson equates our current COVID-19 reality with entering the belly of the whale or belly of the beast. As levels of infection fluctuate worldwide and we find ourselves months into isolation with no clear end in sight, she muses “it is hard to say if we are on the other side yet, are we still inside of it completely, or can we see the light? There is a lot of emotion in this time that is kind of unpredictable and everyone’s pace of life has changed dramatically. It is not only a metaphor, but it is allegorical of how everyone has been forced into this journey.”

The title also attaches us to the body, to be within a living thing, which she connects to the physical referents that a lot of the shapes and forms take on in her work. The tempest of emotions and anxieties we feel manifest physically in our bodies, and the pandemic makes us hypersensitive to these sensations. We continually self-monitor for the first signs of fever, the slightest cough, and to make sure we have not lost our sense of smell or taste. As Dolson succinctly puts it, “our emotions in our bodies are really in our guts.”

Dolson is appreciative of Tempus for giving her a platform to explore new ideas post thesis, amidst the pandemic. She explains that the timing was especially beneficial, as it “really gave me a lot of purpose during the first month and a half that I was back. I was able to come home and put in work drawing 8-10 hours a day and that was absolutely amazing. I think Tempus has a strong sense of what it means to be an art space in that they truly value their artists and look to foster a sense of creativity and programming that makes sense for who they are affiliated with.”

Proceeds from Dolson’s show will go towards helping Tempus fundraise for a paid full-time director position for the gallery. Dolson is also donating a portion of the proceeds from future sales to Black Lives Matter Tampa.

What is next for Jenal Dolson? “Making more work” is her immediate, unflinching answer. Dolson is making a new series of paintings on canvas and she looks forward to waking up each morning and having her studio time. She relishes the daily grind of making work, embodying that true artist-as-hustler mentality, where the balancing act of juggling multiple jobs and projects only energizes her to seek more.

In terms of future exhibitions, Dolson is thrilled to have a solo show this fall at an artist-run space in Benson, Nebraska called The Pet Shop, and she beams when discussing the opportunity. Her close friend Kim Darling, currently a MFA candidate at USF, ran a space at the gallery and helped Dolson make connections in Benson. Dolson also remains in good virtual company through regular studio visits with friends and a gallery in Chicago with which she is enamored. Finally, it has been only days since Dolson moved into an apartment in the port city of Hamilton, Ontario. The industrious city’s “steel town” identity matches her own tenacious work ethic. She is drawn to the city’s strong local arts scene, where she can make her marks on the community. There is also a lovely blend of nature and rich architectural history that she is wasting no time in exploring. Dolson is eager to create her place in this new environment, and everywhere she looks she absorbs new lines, new shapes, new textures, new patterns, and new objects, searching for another source of inspiration around every corner.

Into the Belly ran from May 30-June 12 and it can still be viewed on the Tempus Projects Instagram account. For more information about Jenal Dolson, you can visit her website and Instagram account. You can also learn more about the 2020 MFA exhibition on the USF Contemporary Art Museum website.

James Cartwright earned his M.A. in Art History from USF in 2017. He focuses on cross-cultural exchanges in art production, while occasionally wandering into the realm of contemporary art criticism. He is an adjunct Art History instructor at USF and the University of Tampa, where he uses his liberal arts background to corrupt the impressionable youth of America.