by Jonathan Talit

People don’t think about latex, but when they do, they think about balloons and condoms. Maybe gloves. Latex is just something stretchy that you inflate with air or with a member. A more niche application of latex is making molds. Just like a negative is an inverted copy of the photographed original, molds are negative copies of an actual object. For most people, the mold isn’t the end goal. They need the mold to cast multiple copies.

For Carlie Trosclair, her molds are the end goal. And really, they’re not presented as molds. They’re sculptures; synthetic skins mostly of architectural elements, like staircases and windows, but sometimes natural objects like tree stumps. These spooky husks are on display at Trosclair’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Art – Deland’s downtown gallery, titled “all the lives we ever lived.” Up until April 6th, the exhibition spans several rooms and combines discrete sculptures with broader installations.

I’ve never walked into an exhibition that had an allergy warning. At least, I don’t think so; and I got an arts education in Boston: the American Mecca of rules and legal disclaimers masquerading as etiquette. Granted, some people are allergic to latex, and there are barrels-worth of latex throughout these galleries. Most of the work is made exclusively out of latex.

Trosclair’s near religious fidelity to one medium is impressive. “all the lives we ever lived” is a testament to the quiet authority an artist can convey by sticking to their guns. The challenge, of course, is to not bore with a schtick that runs its course. But Trosclair succeeds in keeping the attention by pushing sizes, densities, lighting, installations, etc. Her weakest attempts are when she fusses with her ingredients. Sometimes, she adorns latex with yarn (unsuccessfully. More on that later.) but the top billing always goes to latex.

As one walks up the steps, they’re welcomed into the Griffin Reception Gallery by a handful of Trosclair’s circular wall pieces. At first, they look like enlarged amoebas or nods to Lee Bontecou’s oculus sculptures. Unlike Bontecou’s pieces, Trosclair’s are translucent and tattered. When viewed up close, they reveal themselves to be molds of plaster ceiling ornaments. The flabby gape in their center was likely where a ceiling fan or chandelier would be anchored. The molds are discolored and worn. Shreds of what looks like cheesecloth fray like fascia on the weaker sections of the pieces. All of this suggests age and the antiquated practice of decorating buildings with plaster ornaments.

But these pieces are just bite-sized introductions. Immediately behind the gallery wall is a room-sized installation titled Chrysalis: Reflections of the Interstitial (2020). The piece consists of several large latex molds surgically stitched together. Once assembled, it creates a long hallway with several passages. The piece stretches down the room such that when one stands at either end of it, they get the feeling of being little Danny Torrance riding his tricycle in the Overlook Hotel.

Whether Chrysalis… recreates an actual hallway or makes one up is unclear. Do Ho Suh’s soft architecture installations come to mind. However, Suh’s work is often neat and taut. Everything’s prim. Trosclair lets her pieces slack a bit. The extra length of the latex walls inChrysalis…curls on the floor like a tongue. This makes the piece look truly exhausted, as if sighing its last breath.

Near the back of the room is the best piece of the show. Mirror (2017) hangs alone next to Chrysalis…and is easy to almost miss. Its title is frank enough. The piece is a pristine latex mold of a mirror. Well, pristine in how much detail is captured, not in terms of color. A single wall mirror and its intestinal, ornamental frame are captured with such accuracy it’s shocking. The mirror section is an off yellow while the frame is a gnarly brown. It’s an intelligent move to have Mirror hang freely instead of adhering to the wall. It gives the piece authority. Despite its small size, Mirror floats with total command like an archangel sent from on high.

What Trosclair does best is capitalize on latex’s limits. It’s a cheap medium that she applies one way: by brush. What makes it cheap? Well, it shrinks when it dries. This creates distortions that throw off senses of scale slightly. When the latex dries, the ultimate mold is usually translucent, making the material appear fragile. But latex is also dated, which harmonizes with Trosclair’s subject matter of historical buildings. This fragility, illustrating how all things wilt before time, adds to the preciousness of the molded objects.

What complicates this preciousness is how dirty latex is. For one, it smells. Ammonia gives latex a sharp odor. Even when the latex is fully dry, there is a faint bite in the air around it. Plus, latex discolors. It starts off-white and, over time, yellows and browns. Even the most sentimental pieces look sordid after a while. This discoloration is exacerbated if the original surface was dirty, like an exterior brick wall. Old paint, tree bark, dirt, and stains are peeled off their host and left on the other side of the latex. The yellowing effect and sharp smell give latex a urinous quality that makes the pieces much more interesting. Otherwise, they’d just be schmaltzy time capsules of grandma’s furniture.

The second room pushes this ick factor. On the left wall, two sculptures are pinned with their wings splayed like taxidermy. They’re titled Goddess (Permutation I) and Locust (Permutation II). Clearly, they’re molded from some architectural decoration or a piece of furniture. The curved, ornamental lines give that away. From what object exactly is not as clear. They have bilateral symmetry, alluding to dissection and Rorschach tests. Both have plenty of negative space to breathe and break.

These pieces are also, clearly, dead. While the first room in the exhibition metaphorically suggests decay, the second room almost literalizes it. The edges of the piece curl and the colors dull as if in necrosis. There’s a haptic effect, too. Even though one can’t touch them, the sculptures look like they were once flexible and are now stiff. Goddess… sags down the middle and reaches into the gallery like Christ on the cross or the figurehead on a ship. Locust…stays flush to the wall. It’s aptly titled: its pale, undulating thorax made me want to dry-heave.

Background: Goddess (Permutation I), 2019

Locust (Permutation II) 2021

Just across the gallery, Cobra stretches nearly four feet in length. Its hood is pinned to the wall and its tail angles towards the floor. This severe line from wall to floor is standard operating procedure for fine art sculpture. Lighting plays more of a role, too, since Cobra casts an undulating shadow. Surrounded by these empty cocoons, one imagines that some insect molted and is now slithering somewhere in the galleries, larger than it was before.

Lighting can really make or break Trosclair’s spell. In the same gallery, Letters From A Domicile (brick wall) hangs from floor to ceiling. The latex is molded from the exterior of the building, including its door, window, and supportive brick wall. Since the latex brings with it the stains of the brick, there is noticeable discoloration. Light passes through more intensely on the “purer” latex of the door and windows. Since Letters…hangs almost in the middle of the gallery, one is allowed to walk around and “see behind the curtain.”

Just to its left, however, a separate window piece hangs with no direct lighting and becomes totally inert. It’s one thing to make art that brings attention to the ignored objects and spaces of our day-to-day lives. It’s another thing to just place art in a gallery and ignore it. Alone together (four doors) has some direct lighting and reads more purposeful. Despite somesatisfying, blocky cast shadows, it still appears somewhat disregarded. The piece is four separate latex doors grouped in a quadrant. Their feet don’t touch the ground. These ghouls gavotte together but only half are lit. This breaks the rhythm that the piece itself establishes.

Some of these lighting failures are attributed to the wide-open space of a gallery. It’s difficult to light multiple translucent works when some are wall pieces and free-floating pieces, small and large. But the job is the job. Relics of passage is given a nook to focus its own lighting, and the results show. It’s also one of the most precarious pieces in the exhibition. Relics…is the final section of a staircase, including the banister and bone-thin balusters. It’s perfectly lit to shine in all its urinal-stained glory. The downward slope, rounded installation, and thin skin create an image of a gradual decline, like a woman aging gracefully. Without the right lighting, the impact of this piece would become muffled.

The final room contains the newest work. Here, Trosclair leaves behind most of her Leatherface-inspired domestic mementos. The natural world has become the new headliner. Trosclair brushed latex onto trees, usually their trunks, and presented the peeled surfaces. The latex isn’t cleaned. The peeled latex exfoliates the tree and brings all the bark and colors with it. The loudest piece is on the floor, titled Woodland Terrains. A tree stump, the nucleus, is surrounded by a ring of tree bark. Translucency is no more, piss-stained or not. Woodland Terrains is so dense with color and texture that it looks like a high relief copy. It’s a true still life. The work feels weightier now, even though it’s about as thin as the earlier work.

Of course, there is a connection between latex and trees: that’s where latex comes from. In that way, the final room is Trosclair coming full circle with her material. Most of the pieces in this room use Woodland Ruins’s unraveled globe format. The wall pieces let one get closer; pull the viewer in with the hairline-fracture detail of tree bark wrinkles. There’s so much subtly in Woodland Terrains II, for example, that you almost miss the blood red yarn woven into certain sections. Admittedly, Trosclair weaves them elegantly here. But once noticed, one wonders why alter such a quietly beautiful and confident piece with some string from Michael’s? Why isn’t the latex enough now?

Artists are perpetually allowed to give it the old college try. Deservedly, Trosclair’s openness to display experimental works should be appreciated. That just doesn’t mean they work. Propagation I (triptych) combines an actual piece of tree bark, her signature latex, and Carolina red clay. While there are some interesting textures in the transitions from one material to another, these are fleeting moments of success. Propagation I (triptych) looks fussy and clunky, like a few square pegs being forced into not enough round holes. The other propagations in the series, II and III, are more convincing, especially the simpler elegance of Propagation II (triptych). Even still, they don’t totally sell it. From the removed perspective of the viewer, the larger issue is that these experiments literalize the materials and their subject: “I like latex. Latex comes from trees. Thus, I’ll put latex next to tree, and that will make meaning.” Oooga-booga.

From the hands-on perspective of an artist, the issue with these experiments is that they involve combing separate materials into one sculpture. This hasn’t yet fallen under Trosclair’s purview. The material was always latex, always brushed, plus whatever it brought along with it once peeled. Maybe some structural supports or sewn adornments here and there, but those were ancillary adjustments. Latex was the core. Now, these experiments are equal parts latex, equalparts mud, and equal parts stick. Assembling multiple materials into one, cohesive artwork is just a different skillset that Trosclair hasn’t sharpened – yet.

Successful or not, none of this work is really new. No big deal. There is an extensive family tree of artists who laid materials somewhat bare, who used architecture to highlight empty space as important as the things that inhabited it, who altered personal objects to convey poetry and carnage, whose work rotted in real time, whose art was an impression of another thing instead of the original itself.

The mother arachnid at the center of this spiderweb family is Eva Hesse. Hesse’s work is often celebrated for its transparency: just letting the materials do their thing. This never fully squared with me. For one, the materials are manipulated, which is exactly what artists do: manipulate. It’s not all chance. There’s an author organizing all this. These decisions could and should be made with a large degree of intuition, but they’re made, nonetheless.

Also, just how transparent are the materials? I think Hesse’s power came from people not knowing just what they were looking at. Her sculptures were clearly made by hand, but how? Viewers likely intuited that the materials were visceral and ordinary, but the whole was still greater than the sum of its parts. Today, I bet Hesse’s ingredients are even more foreign. Our world is too convenient and technologically drab. Whether this makes Hesse’s work more powerful or more easily dismissed as an echo of an archaic era, I’m not sure.

Art’s resonance comes from its hypocritical cocktail of mystery and clarity. That doesn’t make art dishonest. People don’t like to be tricked or to have art handed to them on a silver, Youtube-recommended platter. Art creates a state of suspended animation by organizing matter in a cauldron of consciousness and spitting out something manmade and alien; elegant and strange. This imbues art with a faint icy quality. Like a distant planet, art isn’t hiding, but our view of it flickers. Not because it tries to: that’s just its nature. Acquiring new information doesn’t change this. We know, for example, that it rains diamonds on Neptune. Does that make Neptune less mysterious?

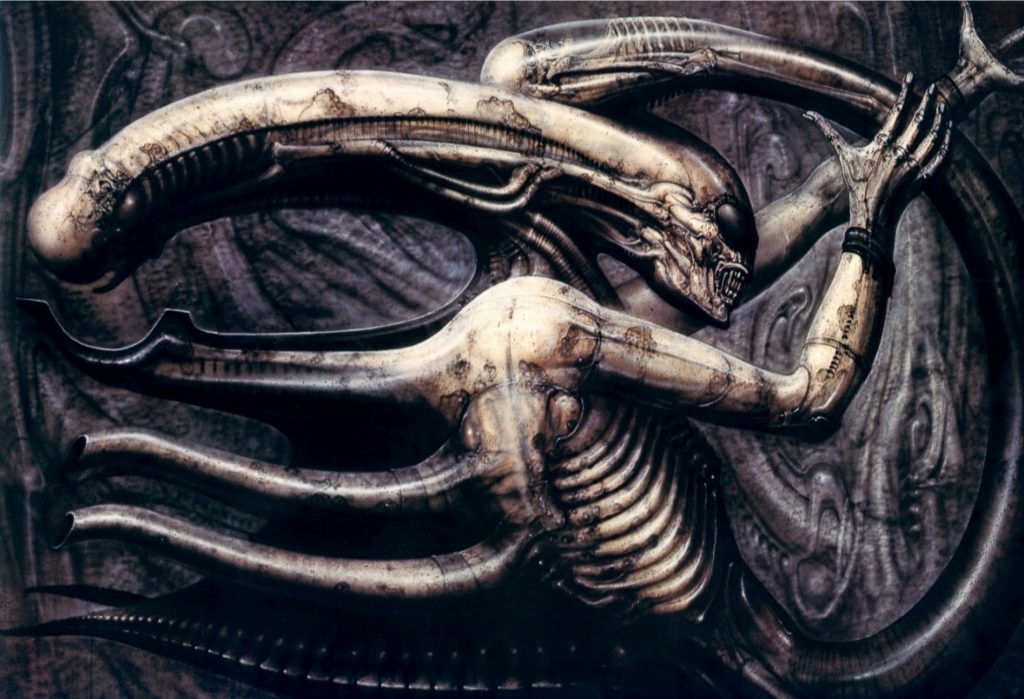

So, too, is Hesse’s work not less mysterious just because she’s “transparent” about what it is. Nor does retroactive analysis of Hesse herself through contemporary ideologies and preoccupations with people’s stories make her work more “accessible.” For all the fecundity and decay of Hesse’s life and work, its core of chilly mystery sustains its power. Even the work of H.R. Giger, Hesse’s brother from another mother, doesn’t have the same impact. Culturally, there’s no question: Giger wins. But sculpture for sculpture, Giger’s work reads more illustrative, compulsive, even manufactured. Hesse’s work breathes. There’s a soft, grimy gravitas to Hesse’s sculptures that suggest a life lived through a powerful, private connection between a human being and material. The sculptures are the throbbing artifacts of this relationship now long turned to dust. Long live the queen.

Aluminum, fiberglass, plastic. Centre Pompidou © The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

“all the lives we ever lived” is an engaging and worthwhile exhibition that is equally transparent about the materials, but it could benefit from a little ice. Carlie Trosclair is clearly formed: she knows what she likes and what she doesn’t like. That’s great. But why force the meaning? The title alone, in its E. E. Cummings lowercase, insists a little too hard on a poetic reading of the work. Trosclair doesn’t need flowery exhibition names or poignant artwork titles to direct the viewer toward meaning. Her instincts are strong. Her skills are refined. Her sculptures pulse with earnest, grotesque mystery. Let them live.

The exhibition “all the lives we ever lived” is on view at the Museum of Art – Deland’s downtown gallery in Deland, Florida, through Sunday, April 6, 2025. The Downtown Gallery and Museum Store are located at 100 N. Woodland Blvd. on the corner of N. Woodland Blvd. and New York Ave. in Downtown DeLand.

Artist Carlie Trosclair lives and works in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Bay Art Files contributor Jonathan Talit is an artist currently based in Orlando. He received his BFA from Boston University and recently received his MFA from the University of South Florida, Tampa. He makes sculptures, essays, exhibitions, friends, fun, and occasionally money.