“My engagement with art has something to do with [its] mystery, a continuous exploration of how it is put together.” Christian Viveros-Fauné

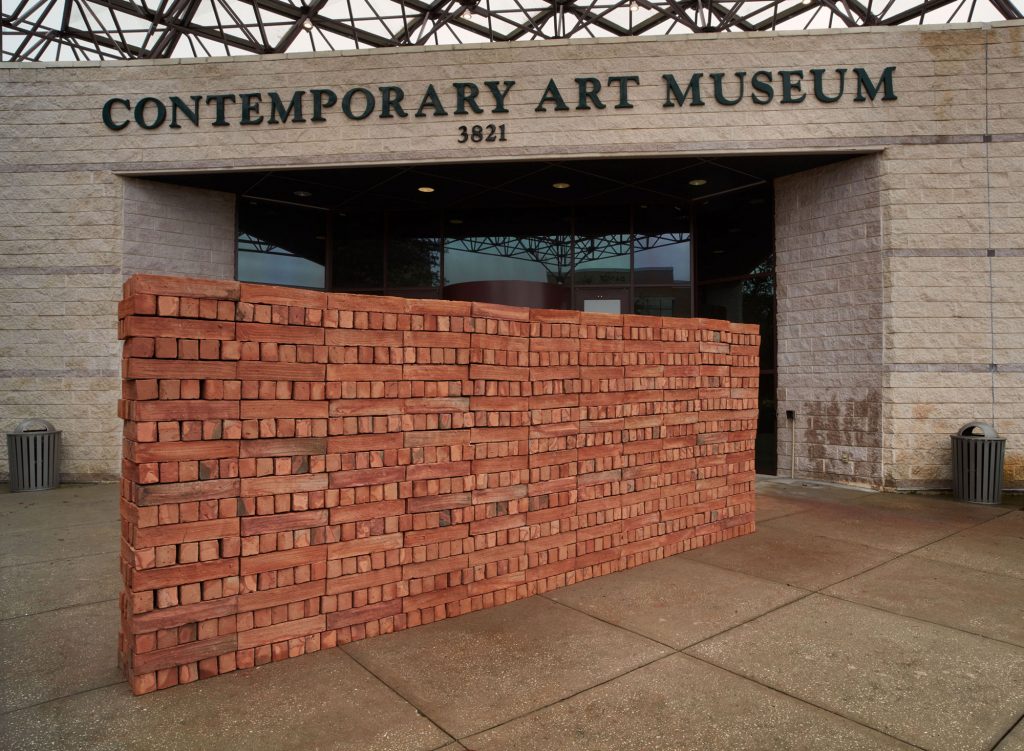

Christian Viveros-Fauné is an internationally respected independent art critic and curator. His appointment as Curator-at-Large to the University of South Florida’s Contemporary Art Museum (USFCAM) in August of 2018 launched a series of politically and socially engaged exhibitions that have further linked Tampa Bay to current trends in the global art world.

Interview conducted and transcribed by Amanda Poss in May of 2019.

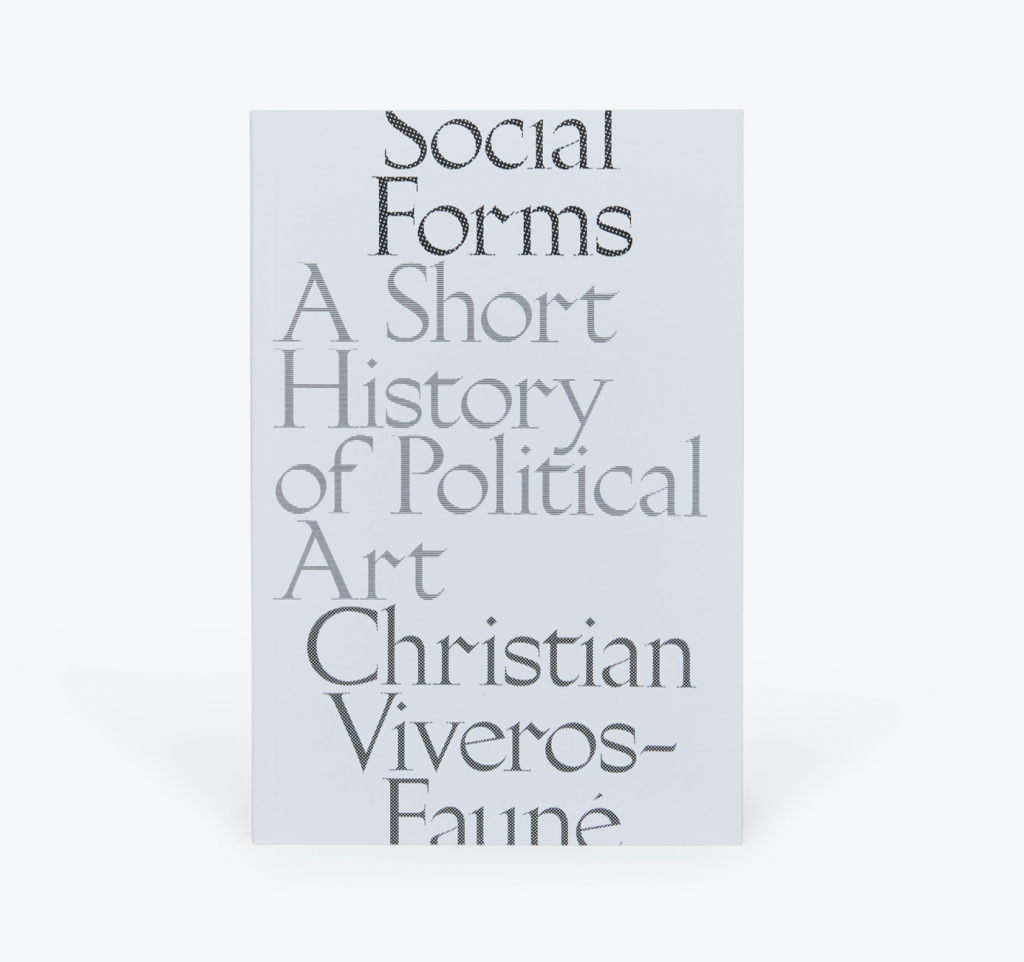

Amanda Poss: I was reading your new book Social Forms: A Short History of Political Art, and in the introduction you cite a trip to the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. when you were twelve where you saw four Rothko paintings. You said this experience was something that “energized” you, and that the paintings “lodged themselves deep into [your] memory.” With this as your catalyst into art appreciation as a child, would you also describe your initial steps into the art world as a professional?

Christian Viveros-Fauné: Those were my initial steps as recounted in the introduction, which reads in part as a portrait of the critic as a young man. At some point I figured out that there was this thing that was mysterious to me–and that actually remains mysterious to me, simply because I can’t make [art], I can’t do it. You know there are people who can’t dance and you say “they have two left feet,” well, I can’t draw, I can’t paint, I can’t do either because I have two left hands so to speak, so I write. My engagement with art has something to do with [its] mystery; it’s a continuous exploration of how art is materially put together, how pigment is pushed around cloth, for instance, to make a picture. That has always seemed to be, to me, kind of miraculous.

I had another experience in my early twenties, when I went to live in Europe. I was always a writer, or a writer wannabe…(laughs)…this was definitely during the writer wannabe period… and I figured out that hanging out with artists was a lot more interesting than hanging out with writers. Writers tend to be shut-ins, they spend a lot of time alone. Being a professional writer is a lonely experience, whereas artists have to get out into the world and show their work at least once or twice a year, so art making has always been far more public. Writers, on the other hand, could spend two years, five years, ten years, basically working on the same project…. So, like I said, I found that artists were a lot more interesting to hang out with. Eventually I entered an artist studio, an actual professional artist, someone who got paid for making paintings and exhibiting them, and I remember being floored by the idea that people could push pigment around to make meaning in ways parallel to how I wanted to make meaning with words. That was a real revelation, it has stayed with me, and is a gift that keeps on giving. I find myself continually inspired, surprised, and amazed by individuals who have made a life from making this kind of meaning consistently.

AP: That brings me nicely to my next point: you have a tremendous CV, with a wide array of experiences and accolades. As someone who has done quite a lot of independent writing and curating, what sort of opportunities/possibilities excite you most about working within USFCAM, which is an institutional but also academic setting?

CVF: That’s a really good question. I’ve long had a career as a writer who moonlights as a curator… meaning, I arrive at an institution and put together a show, but I rarely get to do a second exhibition at the same institution. And that independence comes with significant freedoms, but it also has some drawbacks, right? Not only is working independently unsteady work, but being at an institution longer than single exhibition can mean that you make a bigger impact than just one good show…

AP: One moment, as opposed to a successive series of them.

CVF: Exactly! And that’s really the sort of thing that attracted me to the idea of working at USFCAM. Margaret Miller is largely at fault-slash-deserves the credit for bringing me here. The way she proposed the position was very liberating. For me, ultimately, it was largely about being able to do something at an institution that offered significant freedoms conceptually and curatorially, but that also allows for the opportunity to be able to do a series of exhibitions, with the added bonus that the university is the enveloping organization That is, USFCAM operates in an environment geared towards education, rather than making museum trustees happy.

AP: Which is really different.

CVF: Yes, very different! So, yeah, I think it’s turned out to be a really good fit. There’s also the value of doing things on this campus and in Tampa as opposed to in New York. New York is arguably the center of the art world, it has long been the center of money in the art world. A lot of important art is seen in cities like London and New York, and that is obviously significant on its face… [but] there a lot of cultural phenomena that fail to register in New York because there’s not enough money attached to them, and that’s very unfortunate. Ideas that run contrary to the art market tend to do better elsewhere, they tend to take root in places other than New York. In my book I talk about groundbreaking artists like Rick Lowe. He has given plenty of talks in New York but he has never had a show there, he has never participated in the Whitney Biennial, which is insane, seeing as he’s one of the most influential artists living today. Same thing with Theaster Gates. Social practice in general, which is more than a decade old, has gotten very little play in New York and I think that tells you a lot.

USF Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Will Lytch.

AP: That brings me to my next point. In an interview you did back in 2016 with Brett Wallace for Conversation Project NYC, you were asked: “What should a great show seek to accomplish?” In your response, you mentioned that art should “illustrate [critically] where art/culture is today,” and that you see this happening more in secondary and tertiary cities around the world, as opposed to New York. Do you still feel that way (it sounds like you do), and do you feel that Tampa could be one of these cities?

CVF: I hope so! Let me answer the second part of your question first: I sincerely hope so, and I know my colleagues at USFCAM hope so. We have made inroads and will continue to make inroads in that direction. I’m not sure Tampa has become a secondary or tertiary cultural hub yet, but I do see green shoots suggesting, given a number of crucial synergies, that such a thing could happen. What I like about Tampa currently is that it presents an environment in which ideas can be profiled anew and redefined, which I personally find to be very appealing.

USF Contemporary Art Museum. Photo by Will Lytch.

AP: Now let’s talk about something a bit broader. What does it mean to you to be a curator?

CVF: I don’t really subscribe to the idea of a curator as an author. That is, I don’t like the situation where the curator supplants the artist as an author. I like to think of the role of the curator as a chief collaborator, someone who helps articulate, who helps put discrete works together, like in a group exhibition. Or, if we’re talking about mounting a solo exhibition, [the curator] helps create the context for the work. Curatorial work is, in part, a function of getting art out of the studio. Many artists work long hours with the doors closed to the outside world. Then the work comes out for exhibitions. In a gallery situation, the dealer, the gallerist, hopefully helps the artist articulate his or her vision. In a museum, it’s the curator who helps in making the symbolic meaning circulate. In those circumstances, the curator functions like an an interlocutor–a chief believer in the work–whom the artist can also talk to and figure out the best cultural angle in which to position his or her art.

(Laughs) That was kind of a wordy and non-specific definition….

AP: That’s perfectly fine! I was curious what it meant to you (specifically), because anyone could cite sort of a textbook definition or current theories but everyone has their own approach.

CVF: Possibly because I am very much a generalist as a writer and curator, I really do think there’s an important aspect of editing and interpreting in curating. At their best, curators act like editors for artists. That’s not to say that the curator is necessarily cutting anything from an artist’s production, but, to continue with the editing metaphor, if you’re putting together a collection of ‘essays’–that is, a collection of artworks–then it’s on the editor/curator to make sure that those artworks play as well together as they possibly can. Whether the ‘editor’ is working with a single artist or a group of artists, it’s his or her obligation to establish a relationship of trust and collaboration wherein the best work comes forward and is represented in the best light possible.

USF Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Will Lytch.

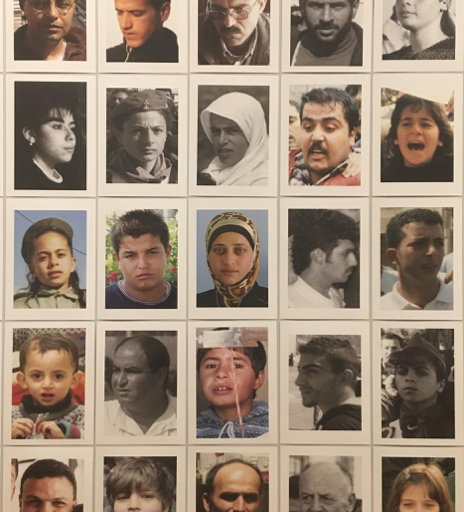

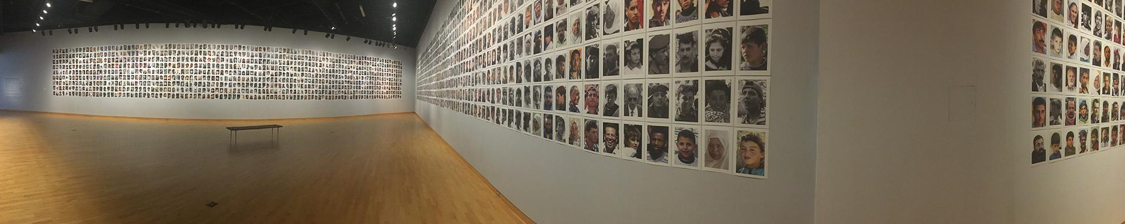

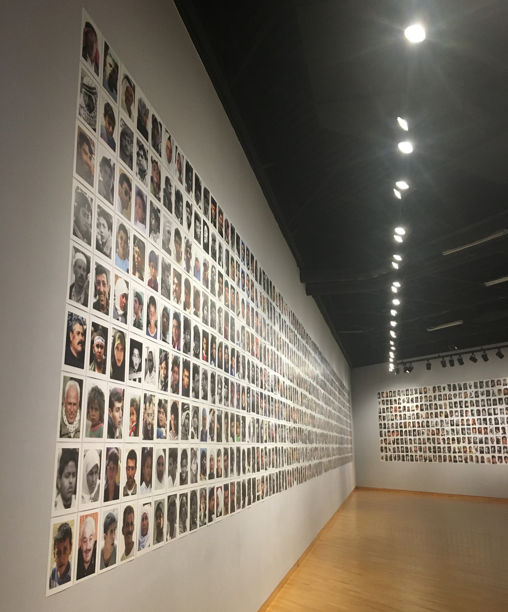

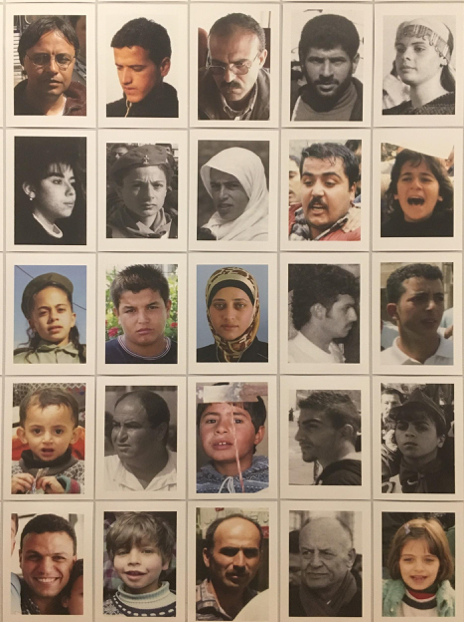

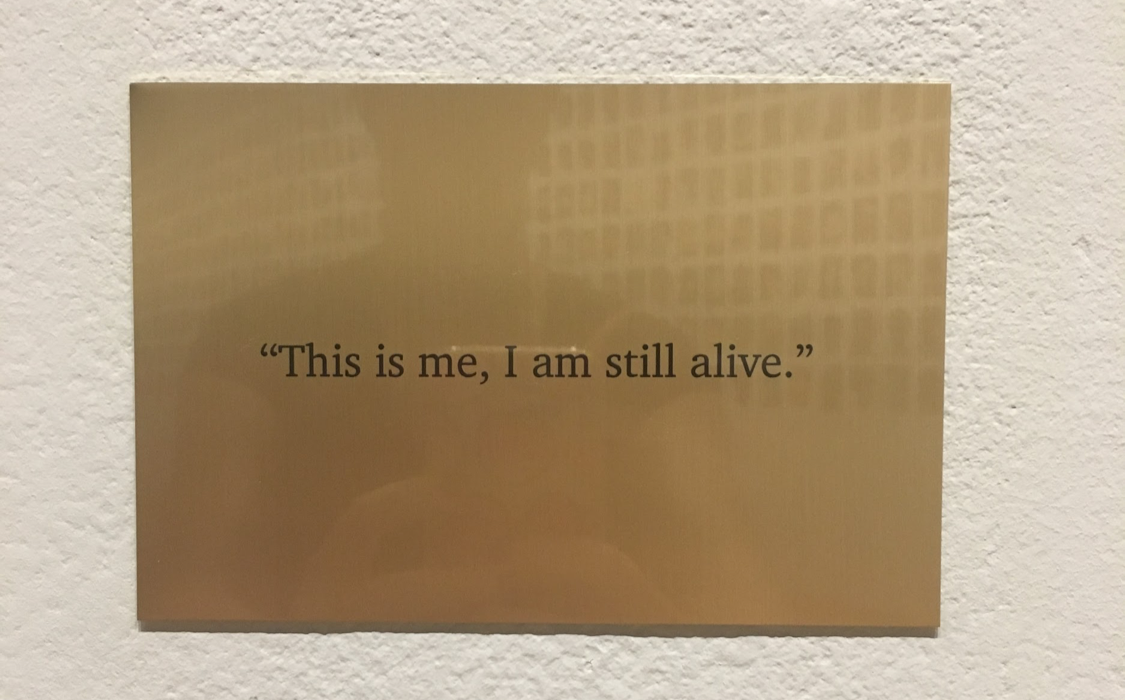

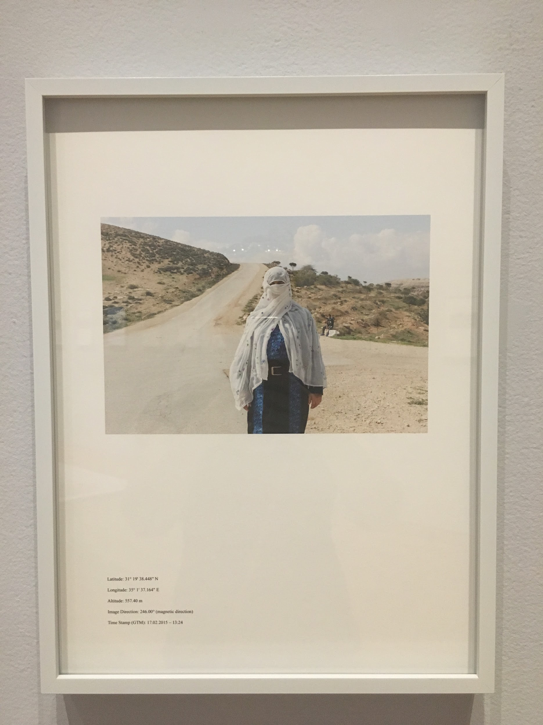

AP: Now I want to go back to something more specific: since you’ve come to Tampa, you started with curating Miki Craftsman: People I met (August – December 2018) and then The Visible Turn: Contemporary Artists Confront Political Invisibility (January – March 2019). What sort of overall trajectory or goal are you setting for yourself as Curator-at-Large at USFCAM?

CVF: Let’s see. Both of those exhibitions you just mentioned can be described, in broad strokes, as highly political, to nod definitively towards issues of social engagement. But what we have on tap for the future, well, some exhibitions are more political than others. Work with a social or political bent has always been my interest, but I don’t want to present those kind of shows exclusively. I think that would make for far too uniform an exhibition program, both for the museum and myself as a curator, so there are other things on tap, [which] I’d rather not discuss right this minute… (Laughs)

AP: No hints? (Laughs)

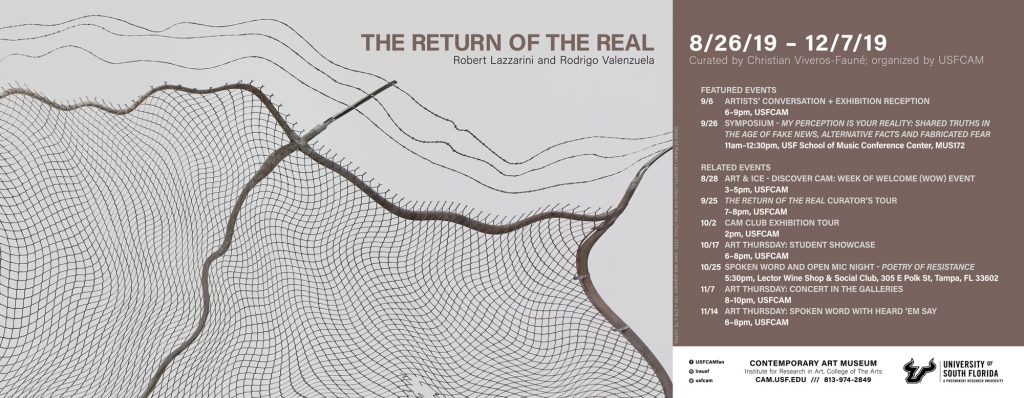

CVF: I don’t necessarily want to give away the the shows that are coming in 2020 or 2021, but what I can tell you is that it will involve an eclectic group of exhibitions. There are going to be several that are a lot more about eye candy [as opposed to] the two shows I’ve done to-date, and even the exhibitions that are heavy on the eye candy will have a significant social component to them. I can say [something] about the next exhibition, which is called The Return of the Real. It’s a two-person show that riffs, or cheekily appropriates, the title from Hal Foster’s The Return of the Real. We’re definitely not using the title in a way that he’d like. (Laughs)

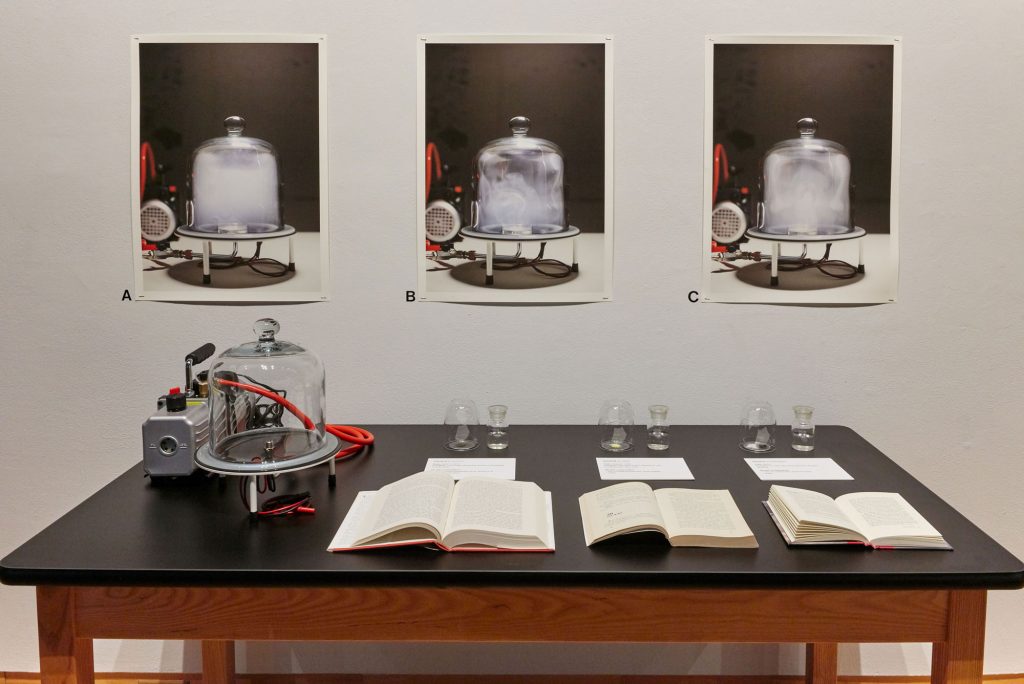

[The exhibition includes] the work of Robert Lazzarini, he makes amazing sculptures that are distorted anamorphically, and another artist who is a generation younger, Rodrigo Valenzuela. Rodrigo is a faculty member at UCLA, [and] a photographer… he’s had about five shows in West Coast museums in the last three years, so he’s well-known out there but not so much on the East Coast. We’re interested in bringing in him [to Tampa] and in being the first institution on the East Coast to showcase his work. Both of these artists are differently committed to amazing acts of re-representation. In both cases, their artworks involve visually stunning, conceptually complex work.

AP: Let’s talk more about your book, Social Forms: A Short History of Political Art. What were you looking for when selecting 50 exemplar works of political art from last 200 years?

CVF: To be honest with you, and I say this every time I present the book, the selection is pseudo-authoritative and very subjective. I write in the introduction to the book that the volume contains 50 essays on what I consider to be the 50 greatest works of political art. Those 50 artworks will invariably be different from another critic’s 50 great works. We might overlap on 10 or 20 artworks, or at least I would hope so.

What these artworks have in common is that they’re all important in the sense that they have all transformed the notion of what people think about when they think about political art. They’ve all put down a marker, they’ve all expanded the definition of both art and politics. Some of these artworks have done so closer to their date of creation, others have not. I start with [Francisco] Goya’s Disasters of War, which was published posthumously, 35 years after his death. He was way too smart to publish those prints in his lifetime because he would have been nailed to the wall by the Spanish monarchy, and if not by the monarchy, then by the Inquisition. But he still made them… and it took more than a decade to put the plates together. So, you have to ask yourself: why would an artist of his stature, late in life, labor so long to put together those 82 plates? [Goya] is basically taking it all in, he’s considering the war, the state of things, the application of reason to human events, weighing how humans respond to social and economic pressure, and ultimately, what happens to society when things fall apart. And what he witnessed is in those prints. I mean, he wasn’t sitting there taking photographs of the war… but somehow or other, through his own observations and other people’s accounts, Goya arrived at the first modern visual record of war and its human cost: what the poet Robert Burns referred to as ”man’s inhumanity to man.”

AP: Some would say even that all art is political, and you address that question in your introduction, but of course you also had to narrow it down to 50 artworks for the book. What do you wish you could have added in?

CVF: I wish I could have added in another fifty artworks. The initial idea was that the book would include a hundred works of political art. I was told by my publisher that they loved the idea of the book, but that we had to slim it down because reproduction rights are just too expensive… (Laughs) Even the reproduction rights on this little book are crazy, so a hundred wasn’t happening, but, yeah, I wish there were specific works that I could have gotten in there, some of them by contemporary artists whom I admire very much…

For example, I wanted to include a major work by the Bruce High Quality Foundation. The group ran a free University, BHQFU, for a whole decade. The collective hasn’t disappeared but it has sort of gone underground. That university was very important. It’s only been a year since it was closed, but it was amazing as a social experiment. The Bruces helped shape an entire generation of artists in what is otherwise a very jaded city. There are many others artworks–contemporary, modern, precursors to the modern–that I would have loved to include and simply could not. Richard Mosse, for example: I would have loved to have included images from his Heat Maps series, which are recent photographs that document the refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East using a military-grade infrared camera that is so sophisticated, it is actually considered a weapon of war.

AP: So what excites or intrigues you most about art right now?

CVF: Its possibilities. The fact that [art], today and in every age, actually gets to reimagine what’s possible. I think that’s really what always amazes me [most] about art. It’s got nothing to do with the actual politics of it, whether I might agree with them or not. It has everything to do with the power of the artist to make something amazing from somebody else’s idea of garbage, to turn the seemingly useless into something that has a renewed purpose…. I mean, that basic gesture is just revolutionary, it’s super radical. I find that kind of surprise, that kind of retooling, to be something that only art can do. There’s something special about art’s lack of use value, its seeming uselessness. At its best and most ambitious that uselessness harbors the potential to create laboratory-like insight… the fact that artists can reimagine worlds is immensely powerful.

USF Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Will Lytch.

AP: One last question. Can art change the world?

CVF: I think that it can, in small and big ways… it’s not [literally] liberty leading the people, and likely never will be, but art does provide, like [the painting] Liberty Leading the People [by Eugène Delacroix], a rallying point for ideas, and we are a very image driven species. Art can change the world, it has done so in the past–I can count at least 50 instances in which it has–and will continue to do so in the future.

The Return of the Real: Robert Lazzarini and Rodrigo Valenzuela

opens at the USF Contemporary Art Museum in Tampa on August 26th and runs through December 7, 2019. The exhibition is curated by Christian Viveros-Fauné, and organized by the USF Contemporary Art Museum.

Artist’s Conversation and Exhibition Reception

Friday, September 6, 6-9 pm

Conversation in the galleries with artists Robert Lazzarini and Robert Valenzuela, and USFCAM Curator-at-lare Christian Viveros-Fauné.

The exhibit reception follows from 7-9pm.

Free and open to the public.

For additional information about a symposium, curator’s talk, spoken word and open mic events, and concerts in the gallery throughout the run of the exhibit, visit the USF Contemporary Art Museum’s website.

Amanda Poss received her MA in Art History from the University of South Florida in 2015 specializing in Modern and Contemporary Art, and a BA from the University of Saint Francis, Fort Wayne, Indiana in 2011. Poss currently holds the position of Gallery Director at Gallery221@Hillsborough Community College, Dale Mabry campus, where she also oversees a growing permanent art collection. She is the former Gallery Director at Blake High School, where she organized and curated exhibits from 2015–2017. Poss also has also held positions at the Scarfone/Hartley Gallery at the University of Tampa as a Gallery Assistant, Adjunct Professor at the University of Tampa, and Adjunct Professor at Hillsborough Community College.