From Chaos to Order: Greek Geometric Art from the Sol Rabin Collection

By Dr. Bob Bianchi

Some of us, I suppose, might initially be reluctant to attend an exhibition featuring 57 relatively small objects from the obscure Geometric period (about 900-700 BCE) of ancient Greek art placed within the context of ancient Greek epic poetry and philosophy. And, I would also imagine, others among us would suspect that reading labels and slugging our way through an accompanying catalogue would be of boringly little interest. We might even echo the sentiments of Callimachus, a Greek poet writing in Alexandria, Egypt, in the 3rd century BCE, who once famously quipped, “A big book is even bigger pain!” But hang on for a second, because big things come in small packages!

The first is the sagacious selection of the objects by Dr. Michael Bennett, Senior Curator of Early Western Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, who curated this exhibition. He made the selection from the approximately 700 in the private collection of Mr. Sol Rabin, who has so exclusively focused for decades on acquiring works of art from that period that his collection is universally considered to be the finest of its kind.

The second is the text, both in the labels and panels in the exhibition and in the catalogue itself. All were written by Dr. Bennett. His main essay represents a decades-long distillation of his own thoughts on the Geometric period. It is felicitously written and peppered with contemporary references so that it is a very easy read. He defines in very understandable terms the ancient Greek concept of beauty and the Greek definition of that term within the context of his overarching discussion of ordering chaos.

His syntheses of the so-called Presocratic philosophers, his elucidation of the principles of Pythagoras, his discussion of Plato’s famed “simile of the cave,” and his presentation of passages from Aristotle’s Metaphysics are presented in such a reader-friendly manner that the complex becomes simple. Interwoven within those discussions is the place of oral, epic poetry of both Hesiod and Homer, appropriate passages of which he quotes in English translation. Despite its simplicity of style, Dr. Bennett’s essay represents “a fundamental reappraisal of the birth of Greek art,” as the Museum’s Executive Director and CEO, Kristen A. Shepherd, so aptly states in her “Foreword.” I could not agree more.

To begin with, the Geometric period was so labeled by modern scholars because of the Geometric patterns found on decorated vases of the period, two of which are featured in the exhibition. The repetitive patterns of their decoration are linked, correctly so, to the repetitive patterns found in the poetry of Homer. Those patterns, I might add, have been suggested to have been based on contemporary, now lost, textiles, ostensibly woven by women, as exemplified in The Odyssey, where Penelope holds her suitors at bay until she completes the weaving of a funerary shroud for Laertes. As an added bonus, visitors to this exhibition might also want to take in the concurrent exhibition, Color Riot! How Color Changed Navajo Textiles, in order to understand just how the repetition of geometric patterns are inherent in the technical mechanics of physical weaving a textile.

One must always remember that the population of the Geometric period of Greece was relatively small, major urban areas rarely containing more than an estimated 5,000 residents. Those residents were neither dominated by the worldwide web nor bombarded by posts on social media. It was an age dominated by oral, epic poetry, and with the exception of Hesiod, Homer was the only show in town. Consequently, the Geometric period of ancient Greek art can indeed be regarded as an age dominated by the epic poetry of Homer. That the poetry of Homer should so dominate an age should come as no surprise. More than 26% of all papyri containing literary texts recovered from the sands of Egypt during the Roman Imperial Period are Homeric! Dr. Bennett is certainly correct, then, in identifying the bronze statuette of a singer accompanying himself on a phorminx as Homer, because the ancient sources clearly state that Hesiod never learned how to play the cithera, the other stringed instrument of the day.

Dr. Bennett’s linking of certain passages from the epics of Homer with the subjects represented on the bronzes is compelling. His discussion of the role of lions in those epics is consistent with his interpretation of the bronze group of a lion attacking a man. The bronzesmith responsible for its creation may also have relied on the Greek artistic convention of portraying the “pregnant moment,” that is a point in the action just prior to its climax. The lion is about to fell its prey, but is not devouring it. The choice is comparable to the scene in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, wherein the protagonist resolves to blind himself, then exits so that the act is anticipated but not consummated on stage.

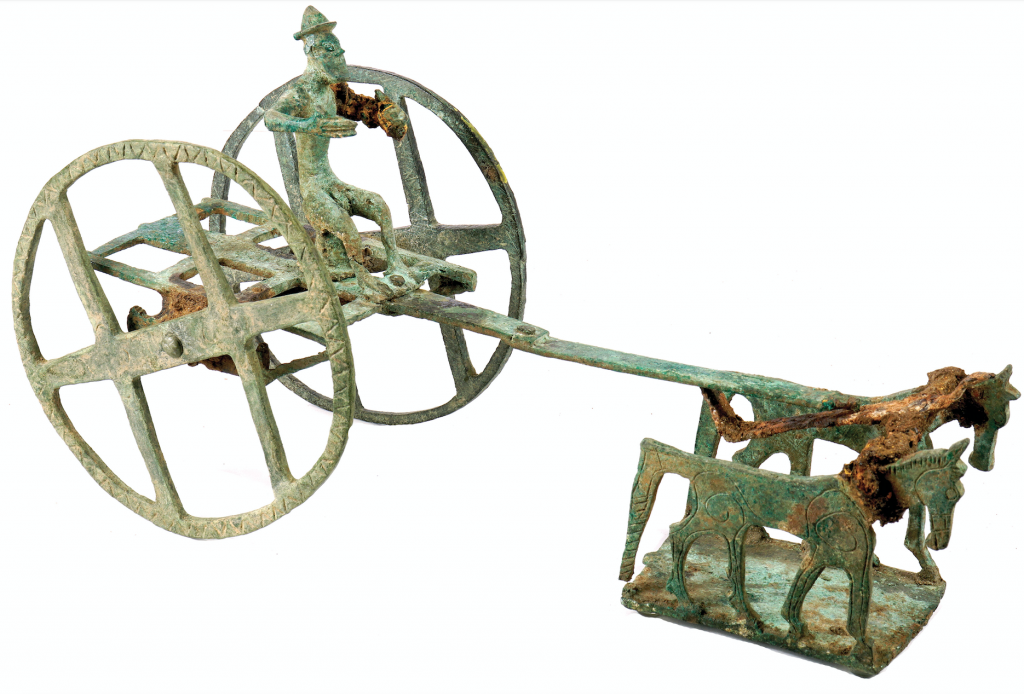

And there are statuettes of horses, horses galore in this exhibition. Here again, Dr. Bennett is doubtless correct when he observes that this repetition of a type is not a mechanical, knee-jerk, simple replication, but represents a repetitive pursuit of perfection and clarity. To my mind, these horses are also evocative of passages in The Iliad (17, 474-8) where the goddess Hera grants one of Achilles’s horses the ability to speak and in so doing predicts the imminent death of his master; and the final lines of that same poem, “…and thus was their burial of Hector, prince of charioteers.”

I would like to conclude with two observations in order to indicate just how thought-provoking this exhibition and its accompany catalogue really are. First, the inclusion of three statuettes of nude women is certainly noteworthy inasmuch as the nude female disappears from the repertoire of Greek art until its reintroduction in the 4th century BCE by Praxiteles. Might these statuettes also represent one of the three goddess whose beauty Paris was to judge, and whose decision sparked the Trojan War? And, second, should we not place Mr. Rabin’s pattern of collecting into the context of the longevity of some of the objects in his collection? The nude, hatted figure driving the horse-drawn cart exhibits unmistakable signs of ancient repairs, suggesting it was long-lived because of its perceived value. I think we owe Mr. Rabin a debt of gratitude for likewise perpetuating the longevity of these objects, the value of which Dr. Bennett has so eloquently explained.

Dr. Bob Bianchi received his Ph.D. from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, after which he served as curator in the Department of Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Middle Eastern Art at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. During his career he has been the recipient of several post-doctoral fellowships, has subsequently served as a curator in museums in the States, Europe, and the Middle East, has excavated for 17 seasons in Egypt, and has taught as an adjunct professor at three universities. To date, he has published 96 books, 378 journal articles, and book reviews, and has appeared in 105 telecasts worldwide. As a critical art historian with a specialization in Ptolemaic Egypt, he continues to explore intercultural artistic connections between Egypt, Greece, and Rome. He recently retired, as chief curator, after almost twenty years of service with the Foundation Gandur pour l’Art, Genéve. Dr. Bianchi continues to publish, address international congresses, and serve as a fine art advisor and certified appraiser to collectors and institutions. He can be reached at Dr.BobBianchi@gmail.com.

From Chaos to Order: Greek Geometric Art from the Sol Rabin Collection is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg in downtown St. Petersburg, Florida, through Sunday, April 11, 2021. A fully illustrated catalogue, written by Dr. Bennett, accompanies the exhibition and is available for purchase online.

RELATED MUSEUM PROGRAMMING

Thursday, January 14, 7 pm- 8:30 pm

From Chaos to Order with Dr. Michael Bennett and Dr. Sol Rabin

An online ZOOM conversation between Senior Curator of Early Western Art Michael Bennett Ph.,D. and art collector Sol Rabin, Ph.D. to discuss the special exhibition. Dr. Rabin has been collecting in this area for over 30 years, and the vast majority of the works in his collection have never been on public display. Free for MFA members; Not-yet members $20. Online registration required.