Interview held August 13, 2020

In the fall of 2019, Grounds4Art@HCC commissioned artist Cecilia Lueza to complete a mural on the Hillsborough Community Collge Dale Mabry Campus focusing on the theme of health and wellness. Community partners, such as the City of Tampa’s Arts & Cultural Affairs division, worked alongside a committee of HCC students, faculty, and staff to create a mural that would reflect upon the theme, taking into account feedback from the community, and to raise awareness of social issues such as food insecurity and mental and emotional health. The project resulted in a mural titled Exuberance that was completed in April 2020 on the exterior of the Social Sciences building. The artistic component was funded by a Community Arts Impact Grant through the Arts Council of Hillsborough County.

Amanda Poss is the Gallery Director of Gallery221@HCC Dale Mabry Campus and the Committee Chair for Grounds4Art@HCC.

Amanda Poss: I wanted to start this conversation with the opportunity for each of you to introduce yourself to our readers.

Cecilia Lueza: I’m a public artist with a focus on sculpture, mural art, and mixed media installations.

Melissa Davies: I work for the City of Tampa in the division of Arts & Cultural Affairs. I’m now in my 16th year there, believe it or not, working solely on public art projects. I’m a Tampa native… and I’m also a board member of the Florida Association of Public Art Professionals.

AP: Thank you both for introducing yourselves! Cecilia, let’s start with you and talk about your work, which can be found all over the Tampa Bay region. You have developed this very cohesive, very recognizable style: bright, colorful, and bold—often full of geometric patterns and shapes found in nature. This is something that you also brought to the mural you completed earlier this year at Hillsborough Community College (HCC), which you titled Exuberance. Could you describe what led you to this particular approach to art making?

CL: Well, it’s interesting because before moving to the United States, I was a very monochromatic type of painter. But I have always had a love of lines and curves and geometric elements. Then I moved to the US and things started changing—gradually I started incorporating more color, experimenting more, and trying to find a balance between geometric elements and color. I think that Florida, with its natural beauty, the light and the vibrancy really influenced my style. As an artist, especially as an art student, I was always looking for inspiration somewhere… and then I finally realized that nature has the answers.

AP: You can definitely feel that reaction to the Floridian landscape in your work. I’m a transplant from the Midwest, and color is something I always very strongly identify with Florida, living down here next to the water, surrounded by the pastels of beach houses, vibrant tropical plants, and the wildlife… So I love that you went from monochrome to this explosion of color in your work.

CL: Yes, because before Tampa Bay I was living in Buenos Aires, and in big cities, like New York, almost everything is monochromatic, buildings are gray, people wear neutral colors—wherever you live, as an artist, that influences you, and can really alter your work.

Lueza’s mural titled Exuberance that was completed in April 2020 and is located on the exterior of the centrally located Social Sciences building on the HCC Dale Mabry campus in Tampa, FL. The project was partially funded by a Community Arts Impact Grant through the Arts Council of Hillsborough County.

Lueza’s mural titled Exuberance that was completed in April 2020 and is located on the exterior of the centrally located Social Sciences building on the HCC Dale Mabry campus in Tampa, FL. The project was partially funded by a Community Arts Impact Grant through the Arts Council of Hillsborough County.AP: So, what specifically inspired your design for Exuberance at HCC?

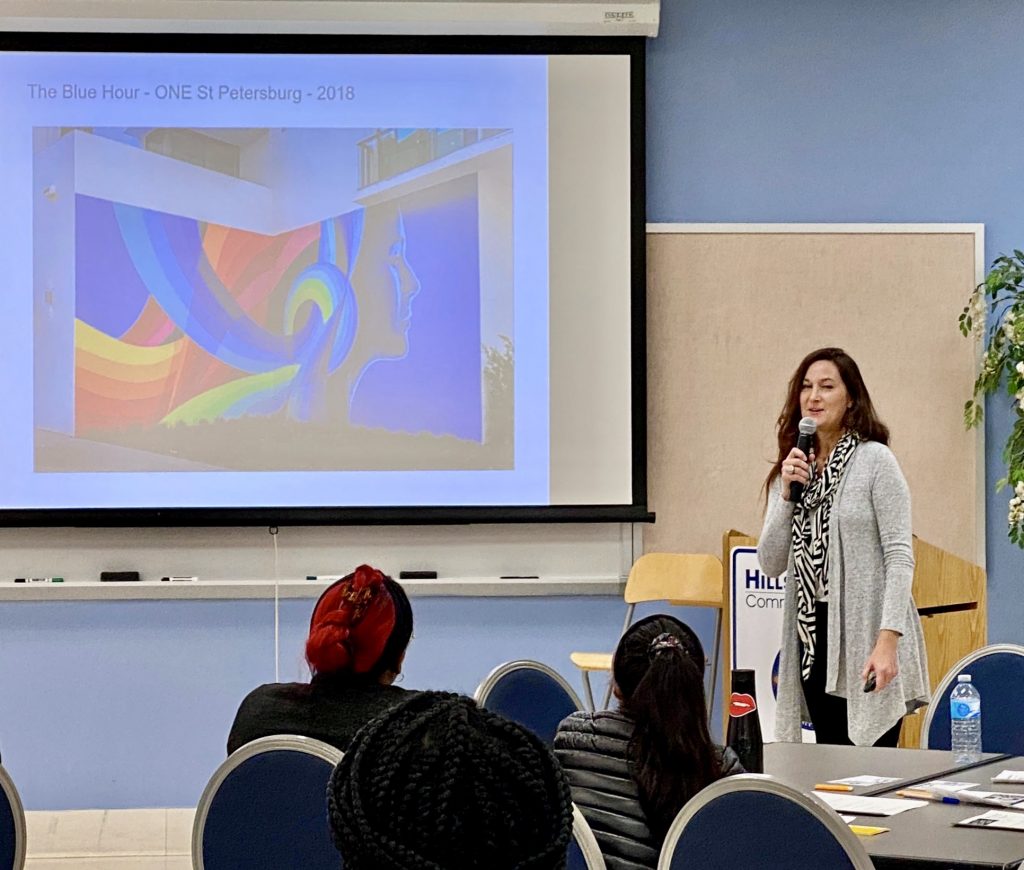

CL: First of all, it was the meeting we had with the community and the students. In this meeting, they learned about my work and we showed them [my] other projects, and they expressed that the colors made them feel amazing, and it was an expression of feeling good in every sense of the word—physically, emotionally, spiritually, mentally. So that was the starting point for me, this concert of colors as a symbol of complete wellness.

AP: Yeah, that was the Community Dialogue event that we hosted back in January, which seems so long ago now… You’ve mentioned in other interviews that you really thrive on meeting people and working with people in different locations, hearing their thoughts and impressions. Was there anything that some of the students or the participants of that event said that led you to this idea of a holistic sense of wellness, a well-being of the spirit?

CL: At one point I was at a table with two or three girls and they were telling me about their expectations for this mural. They wanted to see something that made them happy, something to uplift their spirits, to inspire them and make them feel proud.

AP: I remember you sitting with those girls. During the event I was so impressed by the way you connected with the participants. For instance, you spoke Spanish with them and I think that allowed them to feel comfortable and build a rapport with you—they were in conversation with you for a long time.

CL: Yeah, they were funny and sweet, and many of the students spoke Spanish… so it was easy for me to really connect and understand what they were trying to tell me.

AP: I think they felt like you could really listen to them.

CL: Yes, I love to listen to other people’s stories… I usually prefer to listen to other people.

MD: I think those conversations are really important for a successful end product and installation [of art], because not only does the artist listen and convey that into some level into the design, but also, on the flip side, the people that are involved really take ownership of it, and take pride in the fact that they were part of the process. The cool thing about public art is that every single space is different, every single community is different, and every team is different.

AP: Absolutely. For us, working with community partners and listening to community feedback was especially significant given our project’s focus on health and wellness. I also think, broadly speaking, we’re seeing this intersection of public art and social issues more and more in recent years.

CL: People want to see something that’s not just beautiful, but also meaningful and conveys a message that speaks to them and expresses what they feel… they want to see that they are represented. I think it doesn’t have to be a very complex type of art for people to really connect with it and to find something that’s not only about beauty but also meaning.

MD: There’s so much going on right now, for instance… on the front page [of the news] with Black Lives Matter murals throughout the country. Artists leading social justice projects can be really impactful. For instance, the City of Tampa was approached by the Junior League of Tampa, who wanted to do a mural highlighting the issue of human trafficking, which is a huge problem in Hillsborough County… So we brought in a local artist named Tes One [for the project]… and he met with former victims, organizations that help the victims, the Tampa Police Department and then with the Junior League of Tampa. The end result was a very powerful mural featuring the words “I am not for sale, I am priceless.” Additionally, in the upper corner, the artist added the human trafficking hotline. The location of the mural was situated in an area that is right by the bus station… and between the location and raising awareness… if we just reached one person, you know? A spin-off of that project is that Tes One brought in another local artist, Jay Giroux, who took the theme “I am priceless” and installed posters at a lot of the bus stops throughout the city of Hillsborough County and the City of Tampa.

AP: So, Melissa, in your view, how have public art projects have grown, developed, or changed in our area from where they started to now?

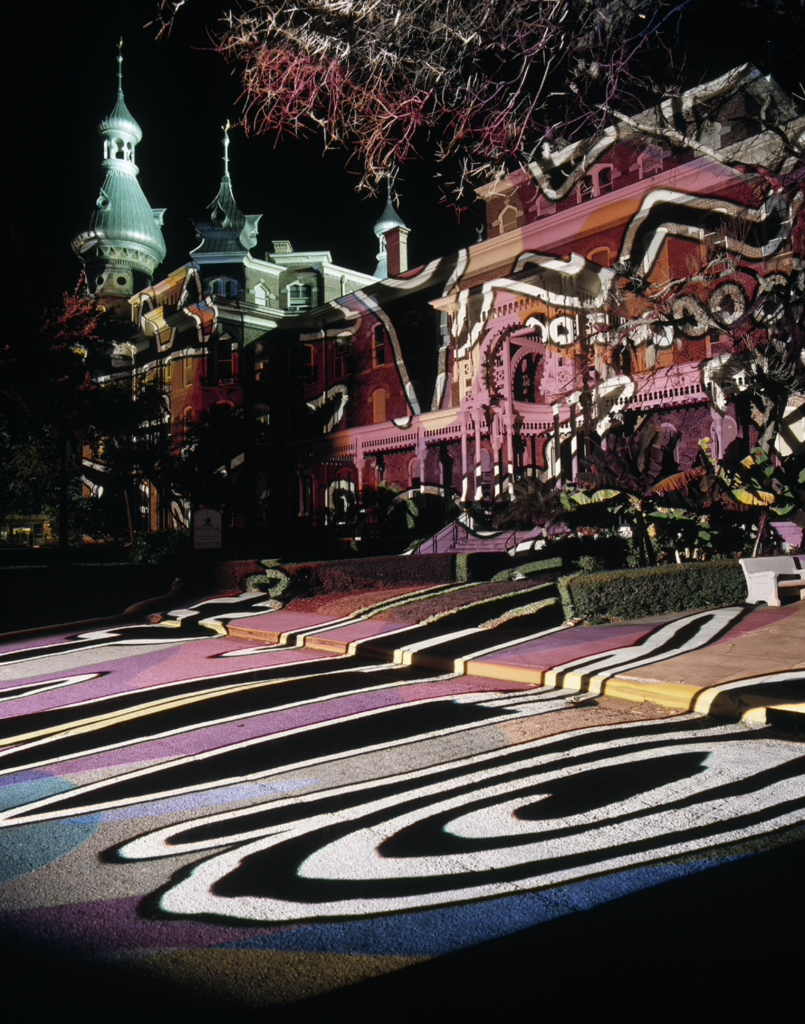

MD: The City of Tampa’s public art program started in 1985. Back then, there were trends in public art like ‘plop art,’ purchasing or commissioning sculptures [for buildings]. In the 90’s there were more traditional public art installations at community centers. Over the last 20 years, under Robin Nigh’s direction, the program has grown through innovative programming that has been recognized by the Americans for the Arts public art network. We had a photographer laureate program, which really grew the public portable works collection, that also documented Tampa throughout a 10 year period, and we also saw technology change within those 10 years pretty rapidly. Lights on Tampa has been running since 2006 and is still going strong. Since Mayor Castor has been in office, we have a new program called Art on the Block, which seeks to get art and artists into neighborhoods. We have a wordsmith that is under contract—which is sort of like a poet laureate. We also have artists Sheila Cowley and Matt Cowley who are husband and wife team. They’re writers based in St. Pete—Cecilia, you may know them…

CL: Yeah, I know them.

MD: He’s a Foley artist and sound engineer and she’s a writer… they’re working with Paul Wilborn and bringing in a team of actors, lyric authors, and literary artists to compile a sensory experience at Centennial Park… Public art can just come in different types of forms: it can be sculpture, sound, all sorts of different elements. Of course, we are still doing many traditional public art installations, but our primary goal is that it makes sense to the community and has context to the site.

AP: Cecilia, how about you? As someone who’s completed numerous artworks in the public realm for many years, what changes have you observed in the attitudes and culture surrounding public art?

CL: What I’m noticing is that people have more knowledge about public art now, I’m seeing public art agencies and committees doing a lot of research, talking with different artists, connecting with their communities and looking at collections in other cities, incorporating more community-based projects to their collections. So, I’m seeing a great, very positive, change.

AP: This is a conversation that parallels public art on a national scale with community-driven projects and programming. The idea of awareness is particularly important and transformative to how we approach public art, creating not just something that’s done to a community, but by, for, and with a community… So related to that point, I wanted to ask: what motivates and inspires both of you to continue working in the realm of public art?

CL: For me, public art is a way to communicate with others. I was very shy as a kid growing up, and I realized that art was both a way to express myself and to connect with others. What I love about art and public art in general is the connections you create with the viewer, with people from all walks of life, especially during the process of bringing the artwork to life. There’s also the challenge of transforming a public space and making the space better than it was… to see this radical transformation. That’s why I want to keep doing it.

MD: I feel the same way. I like the connection to people, not only the community, but also each team, like I mentioned before. Each team is different, each site is different… it’s constantly changing. My primary role is as Project Coordinator, so digging into the details of the logistics is my thing, it’s exciting and fun. Sometimes it can be stressful, but you problem-solve and work with the team… I’ve worked with artists on design teams that have worked through challenges and have just completely transformed the space. I just love seeing the projects come about—being able to work and get to know our artists both locally and from around the world.

AP: I completely agree. For me, managing a public art program wasn’t originally part of my job description when I started working at HCC, but… between community involvement and that moment of radical transformation, as you said, Cecilia, there’s just something magical about it every time it happens. The last question I want to ask is: what have each of you been working on since we completed the mural Exuberance at HCC? Are there any recently completed projects or events on the horizon that we should know about?

CL: Well, I’m working on two sculpture projects: one is for Jacksonville, Florida, and the other one is going to be installed in Tarpon Springs, Florida. Right now, I’m on my way to Kentucky to complete a mural project that’s been in the works for months and months due to coronavirus.

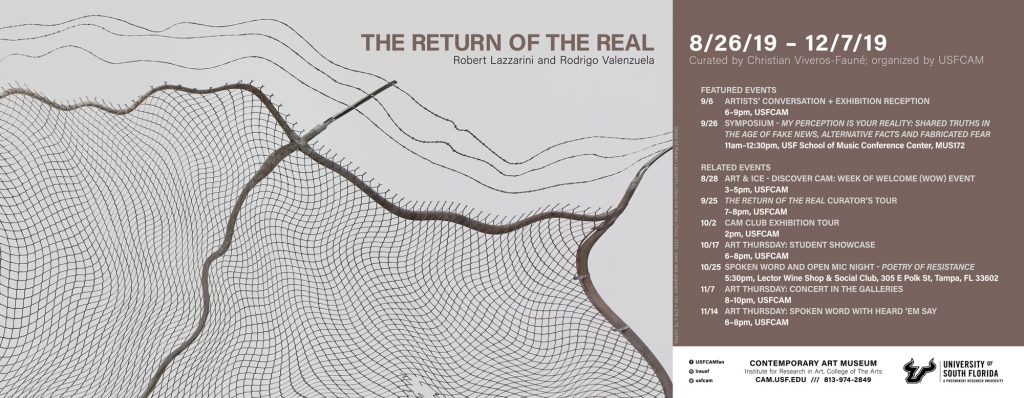

Lights on Tampa rendering courtesy of Erwin Redl.

MD: We actually just finished an installation a couple of weeks ago with a local sports photographer, Matt May. Matt worked with the kids (gymnasts) and took action shots and created a window installation. The kids were thrilled to be a part of this, to see their images in the windows, and to be photographed by someone who shoots professional athletes… We’re also about to do a community project with local artist Ya La’Ford… Then, of course, there are a couple of Lights on Tampa installations. One is Erwin Redl who’s based in Ohio and New York—we actually worked with him in 2006 for Lights on Tampa—and he is under contract to do an installation underneath the Channelside Drive tunnel. We’ve also commissioned artist Andrea Polli, who is based out of Santa Fe, to do a sort of canopy of LED lights to emulate bioluminescence that’s going to be programmed and triggered by sensors. This will be on the Riverwalk under the Harbour Island Bridge. I think it will shine a light, if you will, and bring some positive energy that we need these days.

To learn more about HCC’s public art program, visit: Grounds4Art@HCC.

To learn more about Cecilia Lueza, visit her website.

Learn all about the City of Tampa’s public art program on their website.