by Dr. Robert Steven Bianchi

In 1986, the Tampa Museum of Art acquired 175 ancient objects from the eminent collection of Joseph Veach Noble, thought to comprise the largest private collection of Athenian vases in North America at the time. This acquisition became the cornerstone of the Museum’s burgeoning permanent collection of antiquities. This article (1) highlights significant events in the life and career of Mr. Noble; (2) presents the significant personalities and events which led to the acquisition of his collection by the Tampa Museum of Art; (3) assesses the importance of that collection; and (4) passes in review some of the more interesting objects in the extraordinary exhibition currently on view at the Museum.

JOSEPH VEACH NOBLE

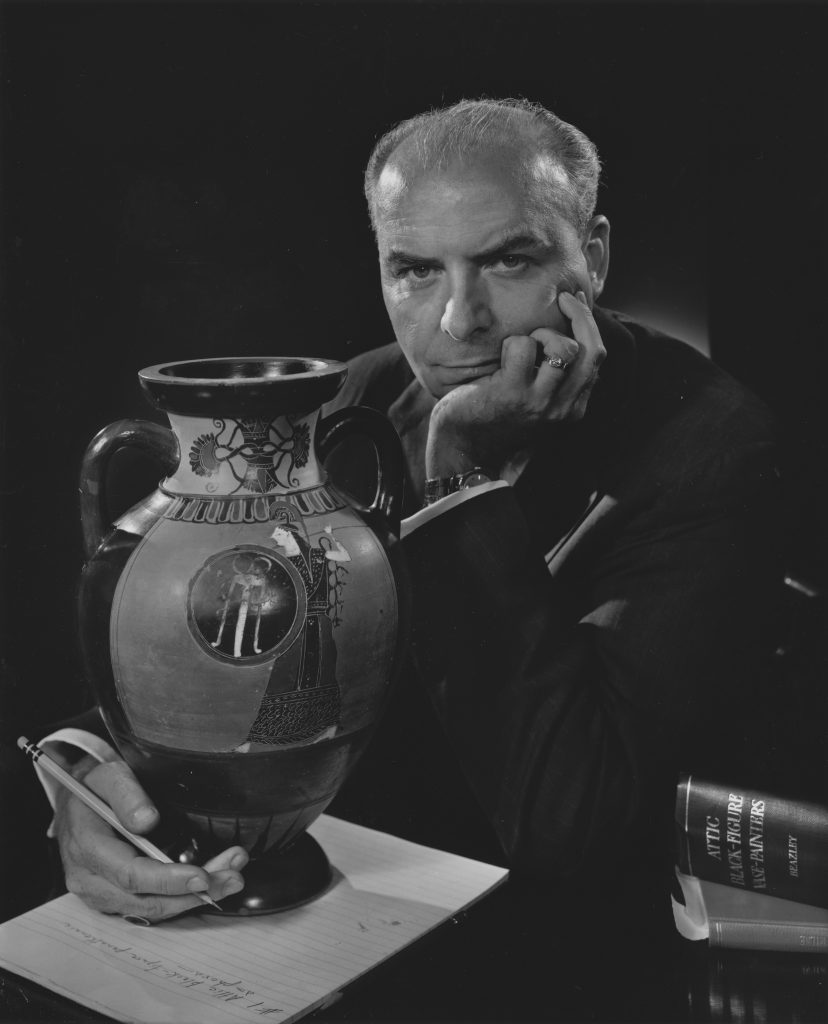

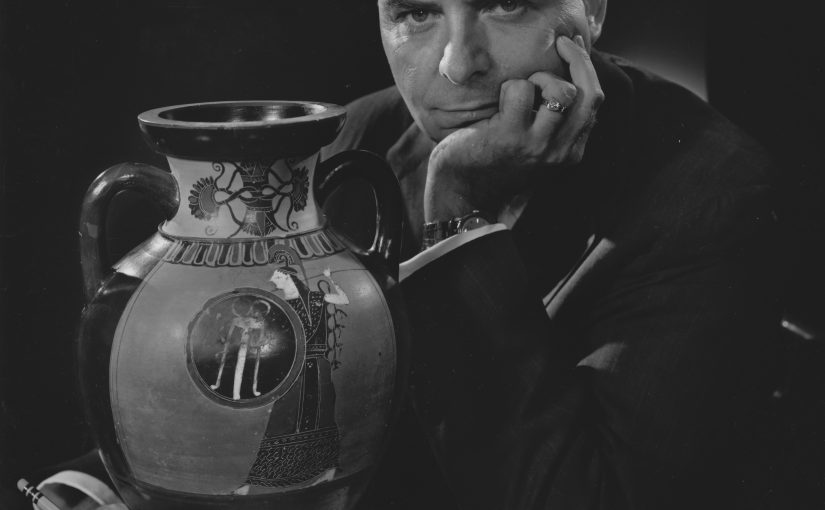

It’s funny sometimes, isn’t it, when an accidental hobby develops into a life-long pursuit which is successfully integrated into one’s professional life? The trajectory of the life and career of Joseph Veach Noble, whose career and collection are being celebrated by the Tampa Museum of Art, is a case in point. (Figure 1)

Joseph Veach Noble, captured in a pensive moment in this photograph taken in 1965, as he thinks about an Attic, black-figure Pan-Athenaic amphora after consulting the seminal work by John Beazley. Vases such as these were awarded to victors of athletic contests staged at Athens, which feature an image of the goddess Athena, the patron of that city.

(Yousuf Karsh (Armenian-born Canadian, 1908-2002), Portrait of Joseph Veach Noble (black and white photograph). Library and Archives Canada, 1987-054, vol. 197, sitting 12547, no. 35.

Photograph courtesy of the Yousuf Karsh Archive)

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

Mr. Noble was born in Philadelphia in 1920. He honed his collecting interests early in life when as a child, he trudged up and down the planted rows of vegetables on his paternal aunt’s small farm in rural New Jersey in search of native American arrow-heads; later, he also collected fossils. His interest in antiquity was piqued during the Saturday mornings spent at programs for school-aged students hosted by the University of Pennsylvania for which he, as a young, project leader, created models of pharaonic and Roman imperial villas, reinforced by visits to the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia with its collection of casts of classical sculpture, and his study of Latin in high school. He took art classes, drawing still-lives in charcoal or conte crayon. Noble would while away the evening hours at home learning how to photograph and develop negatives in the family kitchen turned darkroom by his father who had worked his way through dental school from income earned by photographing dentures and restorations

EMPLOYMENT NOT A DEGREE

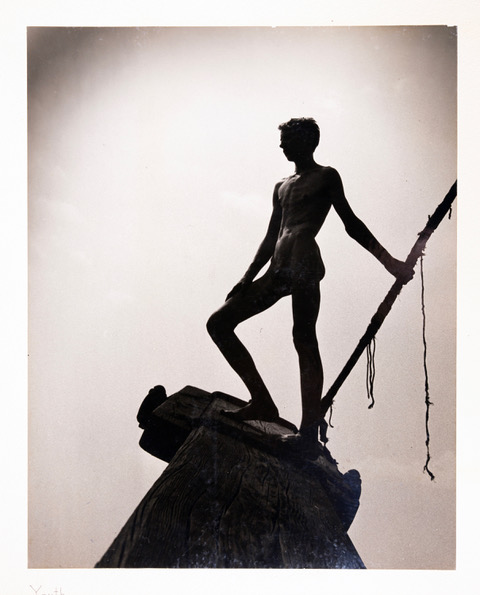

Mr. Noble enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania as a pre-med student, but never graduated because concurrent with attending classes he was also a member of the non-university affiliated Photographic Club of Philadelphia which enabled him to exhibit at the Philadelphia Art Alliance. Six of his photographs are on view in the present exhibition from which one can gain an impression of the scope of his work. (Figure 2) By his own admission, Mr. Noble explained how he impulsively responded to a random call to that Club for a full-time still photographer from a Philadelphia-based firm specializing in what one now terms film. He put his academic studies on the back-burner by attending night classes. He soon abandoned college altogether to devote himself to his full time post in 1946 which, shortly after his hire, required him to master the art of cinematography. Two years later he produced and directed, Photography in Science, which won the 1948 Venice Film Festival award for scientific documentaries. Thereafter Mr. Noble was hired by Film Counselors, Inc. in New York as their Executive Vice-President. He now had motive and opportunity for pursuing his collecting interests in earnest as his quotidian included repeated visits to dealers in New York City and an ever-increasing awareness of dealers abroad, whose inventory could be perused through catalogues and photographs.

Youth by Joseph Veach Noble Mr. Noble’s interests in photography, nurtured in his youth by his father, eventually led to his career as a cinematographer.

(Joseph Veach Noble (American, 1920-2007), Youth (black and white photograph; undated, ca. 1945-1956). Tampa Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph Veach Noble Collection, 1991.009.002)

A VERY CLOSE ENCOUNTER

Mr. Noble’s eureka moment occurred in 1953 when he acquired a very large vase, 21 inches in height, which was described as an Etruscan vase representing a mounted Amazon. Mr. Noble, justifiably proud of this recent acquisition, showed its photo to a European dealer who chanced to be in New York at that time. The dealer urged Mr. Noble to contact Dr. Dietrich von Bothmer, the assistant curator in the Greek and Roman Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who, it was reported, was in the process of writing a book about the Amazons, those legendary, formidable female warriors of ancient Greek mythology. And so an appointment was arranged for November.

As an art advisor myself, I am often placed in a seemingly awkward situation in which I am obliged to inform a collector of a mistake. As Dr. von Bothmer recalls the meeting, his assessment of that vase was ruthless. The vase was not Etruscan. It was created in Apulia, in South Italy. Furthermore, the subject was not a mounted Amazon, but rather a generic South Italian warrior. I t was the dealer who was to be faulted for the erroneous information, but the collector should have been more circumspect in his blanket acceptance of the data. The critique, admittedly disappointing, made a profound impression upon Mr. Noble, who volunteered that, undaunted, he would still seek out that curator’s opinion in future.

HANDS-ON EXPERIMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY

On subsequent visits, Dr. von Bothmer introduced Mr. Noble to his colleague, Christine Alexander. She then orchestrated his European trip in 1954, a kind of pub crawl during which the Noble family visited museums and dealers in Rome, London, and Paris. The culmination of that trip was a personal visit with Homer and Dorothy Thompson, stalwarts of the excavations of the Agora, or market place, of ancient Athens, which was the flag ship of the archaeological activities in Greece of the American School of Classical Studies. That meeting reinforced Mr. Noble’s interest in the technical processes by which Greek vases were crafted as he mined Athenian clay for use in his experiments at home involving a kiln in the basement of his home. On view in the current exhibition are examples of the actual objects that Mr. Noble fired in that kiln. (Figure 4)

These four plaques represent some of the examples of experimental archaeology which Mr. Noble conducted using the kiln in the basement of his home. Here he is experimenting with the chemical composition of the black glaze used by potters in ancient Athens.

(Noble’s experiments [ceramic plaques; undated, ca. early 1960s]. Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection)

Every cloud has a silver lining. A few months later, in January, Professor A. D. Trendall, an internationally recognized authority on South Italian vases who was based in Australia, came to the States and was shown photos of the vase. Professor Trendall’s research had enabled him to group those vases into categories. Mr. Noble’s vase was an outstanding exemplar of one of his groups. In keeping with academic practice, since most of the classical vases were neither signed by potter nor painter, vases are assigned a name generally based on their present location. Accordingly Professor Trendall assigned that specific group of Apulian vases to The Maplewood Painter, named after the town in suburban New Jersey in which Mr. and Mrs. Noble were residing. (figure 3)

Dr. Dietrich von Bothmer’s ruthless critique of this vase which revealed that the mounted warrior was not an Amazon but rather a generic depiction of a warrior cemented his friendship and collaboration with Mr. Noble. This vase was then to become known as the eponymous Maplewood Painter vase, the name given to this classification of vessels by Prof. A. D. Trendall, in honor of the Noble’s hometown in New Jersey where Mr. Noble’s collection was housed.

(Eponymous Maplewood Painter vase (ceramic column krater; Apulia, Italy; late Classical period, ca. 360-350 bce). Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection, Museum Purchase in part with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. William Knight Zewadski, 1986.102)

ULTERIOR MOTIVES

Contact with Dr. von Bothmer continued. He, then, with a hidden agenda of his own, introduced Mr. Noble to Mr. James Joseph Rorimer, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mr. Noble’s account of that visit, in the director’s Manhattan apartment, is fascinating because it demonstrated how Mr. Rorimer’s very long and drawn out conversation was actually, in hindsight, a camouflaged job interview, which lead to Mr. Noble’s appointment in 1956 as that institution’s Operating Administrator.

SCIENCE IN THE SERVICE OF ART

Now, as a colleague of Dr. von Bothmer, Mr. Noble could spend his time every day before his official duties began and after they had ended in prolonged contact with an enormous collection of Greek vases. He now had added resources at his disposal to continue his research into the technical processes by which Greek vases were manufactured because Mr. Noble, as Dr. Suzanne Murray, remarked,

….not only collected the finer examples, but also was interested in the pots that showed mistakes: misfiring that failed to turn figures from red to black, spalling that showed the clay had not been properly prepped, ancient repairs to broken vessels. These less-than-perfect products helped Mr. Noble with his research.

Many of these “mistakes” are on view in this exhibition. (figure 5 )

Mr. Noble was interested in “mistakes” made by ancient potters. This lump of clay is a fragment of a type of wine cup called a kylix. The potter probably crumpled the cup while it was still malleable because its shape did not come out successfully, as compared to Figure 11. Perhaps it was used as a support in the kiln as it was actually fired in this state. It is among the oldest artefacts in the Noble collection.

(Crumpled wine cup (ceramic kylix fragment; Pylos, Messenia, Greece; Mycenaean period, ca. 1400 bce). Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection, 1986.005)

Mr. Noble was also keenly aware of the fact that Ms. Gisela Marie Augusta Richter, a former curator and predecessor of Dr. von Bothmer, had taken classes in throwing and firing pottery which provided her with the hands-on knowledge from which to draw for her publications about aspects of Greek vases. As instructive as those publications were, and still are, their subject matter was restricted to the physical manipulation of the clay, whereas Mr. Noble’s concerns focused on the chemistry involved, such as the component elements of the glazes used and how those elements were effected by the temperature within the kiln. He summarized the results of his investigations in an article published in 1960, which he expanded into a book published five years later. So significant were his observations that a revised edition, published in 1988, still remains one of the first go-to sources.

FINGERING A FORGERY WITH A PEN KNIFE AND A PRIVATE EYE

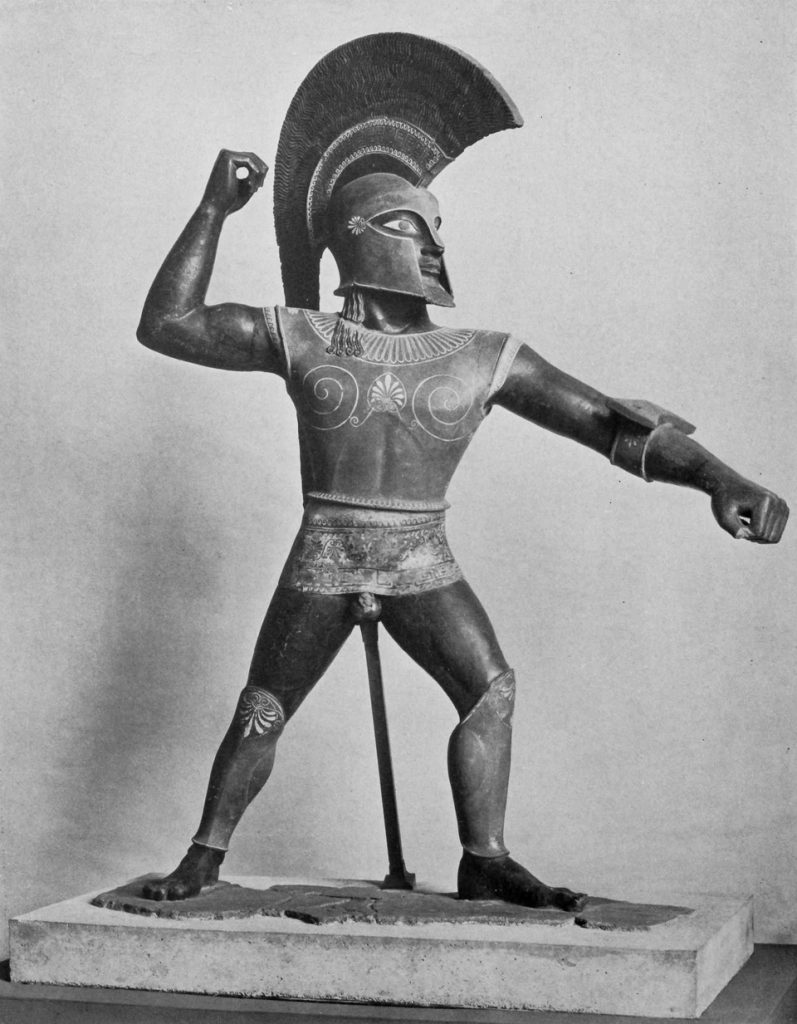

In the late 1950’s, during one of his by now routine visits through the museum’s galleries, his attention was drawn to a monumental, Etruscan terracotta statue of a warrior which had been given pride of place by virtue of the way it was exhibited. (Figure 6) It had become in many ways the trade mark for the museum’s classical collections, although some nay-sayers were progressively expressing grave reservations about its authenticity. Aware of the controversy, Mr. Noble’s attention was arrested by the presence of its black glaze. He reasoned that an analysis of the chemical composition of that glaze might help resolve the question of its authenticity. In order to do so, he needed a sample, which he candidly admitted he obtained by surreptitiously taking his pen-knife out of one of his pockets which he used to scrape off a sample of the glaze when the attention of the gallery’s guard was temporarily distracted. In possession of that precious sample, Mr. Noble recognized he faced a conundrum. If the glaze were tested by the museum’s own staff and deemed to be ancient, conspiracy theorists could claim the analysis was rigged so as not to condemn the authenticity of the warrior. He, therefore, resolved to entrust the sample to a disinterested, but highly competent, third party who would analyze the sample in confidence. Within a short period of time, the results of the spectroscopic analysis were received which revealed that the coloring agent for the glaze was manganese, not iron. Magnanese was never employed before the late Medieval period; it was iron on which the potters of ancient vases exclusively relied as their coloring agent.

The monumental “Etruscan warrior” which was exposed as a modern forgery by Mr. Noble because of his analysis of the black glaze found on its surfaces and his orchestration of cloak-and-dagger face-to-face encounters with the forger.

(Colossal Etruscan terracotta warrior (Metropolitan Museum of Art, acc. no. 21.195). Image taken from Gisela M. A. Richter, “Etruscan Terracotta Warriors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” MMA Papers 6 (1937), pl. 1)

Realizing that corroborating evidence would substantially support his case, Mr. Noble then enlisted Dr. von Bothmer’s assistance. Like every competent curator who meticulously tracks the art market, Dr. von Bothmer had maintained files of dealers, their inventories, their associates, and other data that he deem so necessary to document the provenance, or chain-of-possession, of the classical vases which were the area of his expertise. The two then collated the data from those files with the museum’s own acquisition records which revealed that the warrior had been acquired in pieces over the course of three separate purchases made in 1915, 1916, and 1921.The pieces were then re-assembled by the museum. The vendor’s identify was known, but Dr.von Bothmer’s files revealed that that antiquarian often worked in partnership with another individual who might be able to shed additional light on the purchases. Via a complicated series of cloak-and-dagger operations not unlike those detailed in detective novels, Mr. Noble, via his cinematic connections, secured the services of a private investigator who traveled to Rome and tracked down the partner who was then actively manufacturing fake, bronze Etruscan statuettes for the tourist trade. Maneuvering like a chess master because of the partner’s steadfast reluctance to discuss the matter, Mr. Noble then successfully arranged for Dr. von Bothmer, primed in advance on how to conduct the conversation, to travel to Rome for a face-to-face, during which the partner admitted that he had indeed used bioxide of manganese in his manufacturing of the warrior. Bingo! The museum went public in February 1961 with its announcement on Valentine’s Day that the warrior was indeed counterfeit.

WITH SOME HELP FROM TUTANKHAMUN

Among the objects which were included in the acquisition of the Noble collection is a wooden box, across the lid of which in black ink was scrawled the warning, CAUTION! NATRON. Handle & Unpack with Care. The contents of that box together with other items including linen, pottery vases, and floral wreaths, were part of a find which was excavated by Theodore M. Davis in the Valley of the Kings. The entire find was subsequently associated with the funeral of Tutankhamun, the contents of which were collected by the mortuary priests and purposefully buried in a pit dug expressly for their interment in keeping with religious requirements which prohibited their disposal as trash. In compliance with all existing laws, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was permitted to acquire as acquisitions a selection of objects from that find.

Other hand-written notations on that same lid indicate that the box contained a bag of natron, a naturally occurring mixture of sodium carbonate decahydrate (or soda ash) and sodium bicarbonate (also called baking soda), along with small quantities of sodium chloride and sodium sulfate. (Figure 7) Natron was the primary material employed to desiccate, or dry out, the body, during the mummification process.

The box containing two bags of natron, a naturally occurring mixture of sodium carbonate decahydrate and sodium bicarbonate (also called baking soda), along with small quantities of sodium chloride and sodium sulfate from the so-called Embalmers’ Cache of Tutankhamun. Mr. Noble used that material in his use of experimental archaeology which help him to document the technological processes by which ancient Egyptian faience was manufactures. That box and its contents are on view in this exhibition together with examples of the results of Mr. Noble’s experimentation.

(Bag of natron (linen bag; Valley of the Kings, West Thebes, Egypt; New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1323 bce) and Noble’s experiments (faience figurines and steatite; undated, ca. late 1960s), on view in the exhibition at the Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection. Photography: Paige Bosca)

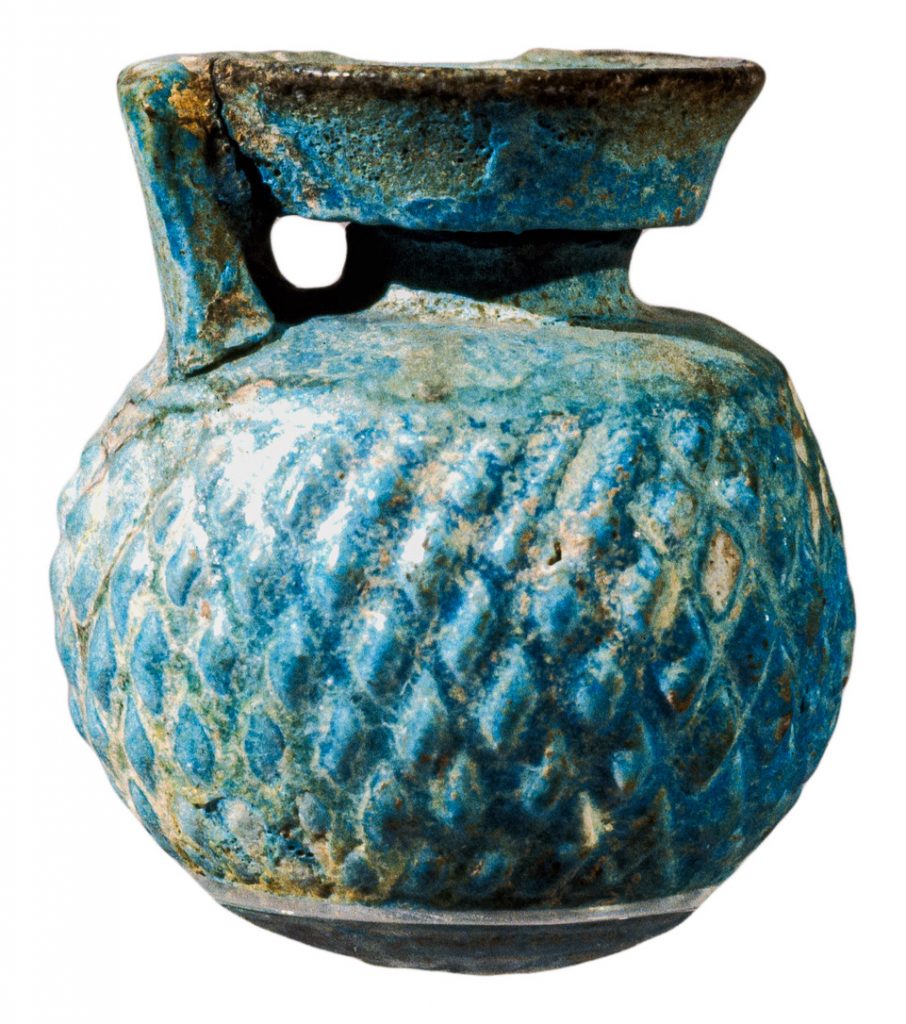

But Mr. Noble understood that natron was also used as a principal ingredient in the manufacture of ancient Egyptian faience, anciently termed tekhenit, a glazed material, generally turquoise-blue in color, which was used to create a wide variety of shining, glistening objects from beads for jewelry to deluxe vases. (Figure 8) His exploration of the technique by which faience was manufactured went hand-in-glove with his work on the black glaze used in the creation of Greek pottery. In 1969 Mr. Noble published the results of his research about the processes by which ancient Egyptian faience was manufactured.

An original, faience aryballos, or ointment flask, from the collection of Mr. Noble, which he used in conjunction with his experimental archaeology to document the technical processes by which faience, an ancient glazed material, was manufactured. The diamond pattern on the walls of this flask were intentionally created so that the vase would not slip from the grasp of the fingers of its owner while applying its slippery contents.

(Diamond-patterned oil flask (faience aryballos; Rhodes, Greece; Archaic period, ca. 600-550 bce). Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection, 1986.006)

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

Mr. Noble resigned his position at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1970 in order to assume the role of director of the Museum of the City of New York. Despite that change in his employment status, Mr. Noble’s reputation as a scholar and consummate connoisseur and collector of classical vases continued unabated and was universally recognized. And as a collector and museum official, he was accustomed to the common practice of lending objects to institutions for temporary exhibitions. So, it was only a matter of course that he was asked and consented to loan three of his vases to the very first exhibition of antiquities ever mounted by the Tampa Museum of Art. That show, Styles and Lifestyles of the Ancient World, premiered here on March 1, 1983. Ms. Genevieve Linnehan, the Curator of Collections (1979-1992) at the Tampa Museum of Art whose speciality was modern art, organized the exhibition, enlisting the assistance of Mr. William Knight Zewadski (“Bill’) and Dr. Suzanne Murray, who had earned her doctorate in ancient art from the University of Minnesota and was affiliated with the University of South Florida.

THE ART OF NETWORKING

PAUL JENNEWEIN AND JOSEPH NOBLE

Paul Jennewein of Philadelphia was a noted American sculptor whose oeuvre included the massive sculptural pediment adorning the façade of the south east entrance of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (figure 9) Jim Jennewein, his son, and Joseph Noble both fellow Philadelphians, were friends who also shared their mutual service on the board of Brookgreen Gardens. It was Joseph Noble who had suggested to Paul Jennewein that he leave his lifework of sculpture to Tampa. That suggestion turned into a bequest in 1978, when approximately 2,500 sculptures, models, drawings, medals, and related ephemera from his estate were bequeathed to the Tampa Bay Art. Part of that collection is now on exhibition C.Paul Jennewein (April 16, 2023–2025) at the Museum through 2025.

These models for the pediment of the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the Philadelphia-based artist C. Paul Jennewein are part of his estate bequeathed to the Tampa Museum of Art. His friendship with Mr. Noble enabled members of his family to network with the team from Tampa Bay in the initial discussions with Mr. Noble which led to the eventual acquisition of the Noble collection by the Tampa Museum of Art.

(C. Paul Jennewein (German-American, 1890-1978), models for the pediment of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, on view in Sketches and Sculptures: A Study of C. Paul Jennewein at the Tampa Museum of Art, June 13, 2020 – February 28, 2021. Photography: Philip LaDeau)

Jim Jennewein’s wife, Joan, would later recall a conversation in which her father-in-law stated that Mr. Noble was reluctant to donate his collection to a large, established institution where it would get lost. If on the other hand, it was given to a smaller museum it would really be seen. Armed with such a position, Jim Jennewein then suggested to Mr. Noble on May 12, 1984 that he give the collection to the Tampa Museum of Art. Mr. Noble countered by stating that he would be willing to sell the collection to the Tampa Museum of Art for one million dollars.

Mr. Zewadski then picked up the ball and continued to run with it. On November 26, 1984 Mr. Noble sent Mr. Zewadski the card catalogue together with seven volumes of photographs of his collection. Mr. Andy Maass then wrote to Mr. Noble, who incidentally was Mr. Maass’s first employer, on February 13, 1985, explaining that although he was only two months into his tenure as director of the Tampa Museum of Art he would be interested in the loan of the collection for a temporary exhibition which would run from December 1985 through February 1986.

AN UNFORESEEN PROBLEM

The planning for such an exhibition ran into a snag because Ms. Genevieve Linnehan was scheduled to take maternity leave. She was of the opinion, which was widely-shared by others, that any effort to acquire the Noble collection would be enhanced by the presence of an individual with an advanced degree in ancient art. The issue was satisfactorily resolved when Dr. Murray, who had already collaborated with Ms. Genevieve Linnehan and Mr. Zewadski on the first exhibition of antiquities at the museum, agreed to serve as the guest curator for the Noble collection.

THE ON-SITE PERSONAL INSPECTION

Mr. Zewadski mobilized Mr. Maass and Dr. Murray on May 22, 1985, for a road trip that brought them to New York and New Jersey where they visited the offices of Mr. Noble in the city and his home in Maplewood. Dr. Murray recalls that the visit was great fun. She saw the Maplewood Krater (Figure 3) sitting on a TV console and the Neptune statue (Figure 10) standing on the stair landing.

It was such a unique combination of the mundane and modern with the precious and antique. He then produced the gold necklace and earrings to show us—so delicate—which his wife had never seen, and seemed a little \reluctant to include in the deal!

The visit concluded with trip to Drew University where some of Mr. Noble’s vases were featured in a loan exhibition. Days later Mr. Zewadski sent the seven volumes of photographs of the Noble collection together with numerous copies of articles which had been published about that collection to Mr. Maass.

The statue of Poseidon/Neptune, the Graeco-Roman god of the sea, which Dr. Murray described as seeing for the first time on a landing of the staircase in the Maplewood home of the Nobles. This statue was one of the sources of inspiration for the special loan exhibition, Poseidon and the Sea: Myth, Cult, and Daily Life, mounted by former curator, Dr. Seth D. Pevnik, which ran at Tampa from June-November 2014 before moving on to its second venue at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.

(Neptune with Dolphin (marble sculpture; Rome, Italy; Roman Imperial period, ca. 50-100 ce), on view in the exhibition at the Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection, 1986.135. Photography: Paige Bosca)

A STRATEGY FOR THE FINANCIAL PACKAGE

Moving quickly within a month, Mr. Maass then formally requested the museum’s board to consider the acquisition of the collection which lead to the immediate formation of a subcommittee of the museum’s Acquisitions Committee whose members were so tasked. The City of Tampa then pledged a contribution of $250,000.00, representing 25% of the asking price.

On July 29, 1985 Mr. Maass wrote to Mr. Norman Hickey, the [Hillsborough] County Administrator, seeking a contribution from the county. He pointed out that the one million dollar price tag was a good deal because the collection had been appraised at $1,737,250.00. Furthermore, if the $250,000.00 were to be used as a downpayment, the collection could be on view as early as December. On September 3, after a very convincing presentation by Messrs. Zewadski and Maass, who aggressively advocated for the purchase, the County voted to commit a quarter of a million dollars, payable over four years, to be applied to the purchase price.

There were still some loose ends to tie up, but the acquisition of the Noble collection for the Tampa Museum of Art was now a done deal, which was celebrated on October 26, at Pavillion V, the gala benefit of the Tampa Museum of Art which foregrounded Mr. Noble as the honoree. (Figure 11)

The principles at Pavillion V (October 26, 1985 ) the gala benefit of the Tampa Museum of Art which foregrounded Mr. Noble as the honoree. From left to right, Mr. Willian Knight Zedwadski, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Veach Noble, Dr. Richard E. and Mary Perry, whose endowment funds the Richard E. Perry Curator of Greek and Roman Art, currently held by Dr. Branko van Oppen de Ruiter.

(Courtesy of M.r. William Knight Zewadski)

MORE WORK IS NEEDED

The Noble Collection Committee, whose members initially convened in Mr. Zewadski’s offices at Trenam Law in Tampa, realized that fundraising required persistent dedication by many people. Lead editorial support by the Tampa Tribune promoted the cause. Donations came from many individuals, the community, and every member of the Museum staff. Noble Collection Committee also addressed a host of related issues including the logistics involved in creating an exhibition.

BEHIND THE SCENES

As one who has been personally involved in over thirty international loan exhibitions over the course of my career, I can only concur with Dr. Murray’s recollections

When the collection arrived at TMA, I was able to help unpack the vases, which was an incredible experience. For an art historian to handle these objects was a gift, although some of the vases, like the very wide, shallow kylix with Herakles and the Nemean lion, seemed so impossibly designed that you wondered at their longevity. (Figure 12)

The kylix, a cup for drinking wine, which, as Dr. Murray recalled, as she unpacked it for the exhibition, was so delicately and fragilely designed that she wondered how it survived the millennia still intact. The shape of this vessel recalls the original appearance of the misfired kylix (Figure 4) that Mr. Noble intentionally collected as one of his potter’s “mistakes.” The view taken depicts the Greek hero Heracles wrestling the Nemean lion, the very first of his legendary Twelve Labors and the one that established the lion skin as his trademark attribute.

(Heracles wrestling the Nemean Lion (ceramic kylix; Attica, Greece; Archaic period, ca. 510-500 bce). Tampa Museum of Art, Joseph Veach Noble Collection, 1986.085)

Dr. Murray then collaborated with Mr. Bob Hellier, the long-serving, very talented Chief Preparator of the Tampa Museum of Art, whose responsibilities included the handling of objects and physically placing them in exhibition cases. Both were confronted with the challenges of displaying the antiquities. Dr. Murray discussed the matter with Mr. Hellier. She recommended that the vases be displayed in a way that would maximize their visibility because some were decorated on both sides whereas others were decorated on both their exteriors and interiors. These then had to be arranged into comprehensible groupings with similar themes and subject matter, such as portrayals of myths, sport, warfare, and daily life. Dr. Murray was also responsible for generating copy for labels and other didactic materials such as wall panels which provided the visitor with valuable information about the exhibition. The accompanying, exhibition catalogue was also on her to-do-list. She observed

The catalogue came out beautifully, a joint effort between Bob Hellier and myself. It contained a complete listing of JVN’s collection, as well as a selection of focus pieces for which I wrote individual essays (several of these had color plates).

Visitors to Joseph Veach Noble: Through the Eye of a Collector should also be aware of the fact that the issues which Dr. Murray and Mr. Hellier were obliged to solve were similar to those resolved by Dr. Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter, Richard E. Perry Curator of Greek and Roman Art, and staff of the Tampa Museum of Art in their collaborative work on this exhibition.

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

Over the course of the next three years with a Florida State Legislative fund drive in place, and the continuing efforts of individuals such as Messrs. Frank Harvey, Ben Norbaum, with assistance from Mr. Charles W. (“Jack”) Sahlman and State Senator John Grant, and attractive terms from Barnett Bank, the financial obligation for the acquisition of the Noble collection was discharged, the final payment having been made in late September 1988.

A NEVER ENDING STORY

Dr. Murray recalls that

when I began teaching my Archaeology of Greece course in the History Department at the University of South Florida, the Noble acquisition provided a fantastic teaching collection, as it did for others. Students were amazed that Tampa had such things.

It subsequently generated the specialized position, the Richard E. Perry Curator of Greek and Roman Art with generous contributions from Costas Lemonopoulos and Dr. and Mrs. Richard E. Perry. This position, which is currently held by Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter, is said to be the most heavily endowed curatorship of any museum in the United States.

The lessons gained from this survey of the life and career of Joseph Veach Noble are simple: Collectors in partnership with museum curators enable collectors to hone their aesthetic judgements, create unlimited opportunities for scientific research, and open pathways for financial support. Such partnerships often result in arrangements by which those private collections enter the public domain where the objects themselves serve as vectors enabling visitors to expand their cultural horizons with an enhanced understanding of a shared past. Such collector-curator partnerships are invariably win-win scenarios.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This article could not have been written if it were not for the willingness of William Knight Zewadski, a principal mover and shaker of the effort to bring the Noble collection to Tampa, to share unselfishly his vast knowledge, insights, personal experiences, notes, and corporate memory with me.

I also wish to express my indebtedness to Dr. Suzanne Murray for her willingness to share her first-hand experiences with me about her involvement with the events associated with the Noble collection in her capacity as guest curator.

ABOUT THE MUSEUM

For more information about the exhibition, Joseph Veach Noble: Through the Eye of a Collector, on view at the Tampa Museum of Art through February 19, 2026, visit the Museum’s website. The Museum has partnered with the Hillsborough County Public Schools to provide a unique tour experience to students in grades 3-8. In 2024, this program, facilitated by visits, discussions, and art-making projects, will serve nearly 15,000 students from the HCPS Transformation Network.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Robert Steven Bianchi, a critical art historian, is currently chief curator of the Ancient Egyptian Museum Shibuya [Tokyo]. During his career “Dr. Bob” has curated exhibitions of both ancient and contemporary art in the States, France, Germany, Israel, Japan, and Switzerland. He advises collectors and is also a certified, USPAP-compliant member of the Appraisers Association of America. He has previously written about exhibitions in the Tampa Bay area for Bay Art Files

Marvelous article which connects the many dots/details of TMA’s acquisition of there Joseph Beach Noble Collection!