Location, Location, Location

Anthony Record and the Museum of Florida Art and Culture

by Jonathan Talit

Driving to Avon Park is just that: driving to Avon Park. The 50-mile stretch of US-27, between the southbound exit on I-4 and the northwest border of Highlands County, begins packed with strip malls, gas stations, and fast-food chains: the trademark scenery of any highway exit. The deeper one drives, the less frequently these landmarks appear until there is nothing to look at but grass, sky, and asphalt. Yet, I couldn’t help but look out even more; to open my eyes wider as the flat land pulled itself closer to the horizon and the sky bent around my windows so dramatically that it appeared to dig at the edges of the earth. It was difficult to imagine people living anywhere near here. Not out of snobbery: it just, quite literally, looked so empty of people.

Of course, that’s not true. People do live in Highlands County and many have for generations. Even more visit to celebrate acute passions: the Mobil 1 Twelve Hours of Sebring car race, sold-out concerts by Rumours, a renowned Fleetwood Mac tribute band, the charming trompe l’oeil murals of Lake Placid, and Toby’s Clown School and Museum. The latter has graduated more than 1,500 clowns since its founding in 1993. Despite appearing sparse, or perhaps because of it, Highlands County is sprinkled with various sites of assembly.

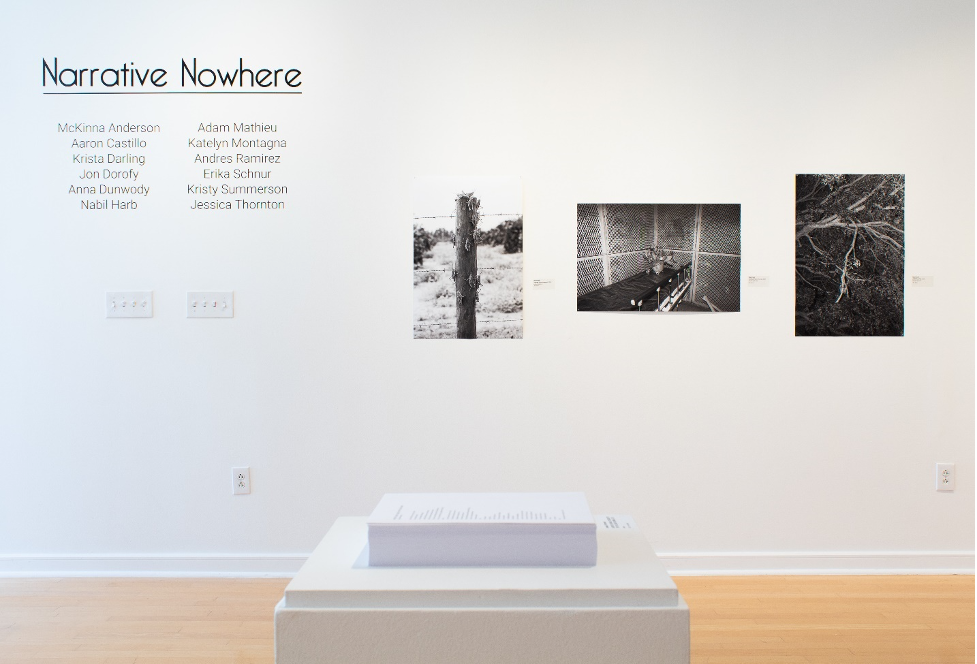

The Museum of Florida Art and Culture, or MOFAC, is one such site. Part of South Florida State College, MOFAC hired Anthony Record as its new curator in March of 2022. Since then, Record has been busy organizing contemporary art exhibitions and managing MOFAC’s permanent collection of historic art and artifacts pertaining to the region. I met with Anthony on a Saturday afternoon, at the pristine campus of SFSC, just two weeks shy of Hurricane Ian pummeling the state, to discuss his new role.

“I’ll show you the concourse, first,” he said as he ushered me inside. The main exhibition space is divided into quadrants (quintets if you include the lobby of the Board Room). The main gallery has two sections: one for contemporary art exhibitions and one for the permanent collection. The third section is the lobby of the music hall.

The fourth is the concourse, which is within the building but outside of the main gallery. It consists of a large, curved wall that follows a hallway between the main gallery and classrooms. Several long canvases line the wall. Technically, they’re canvas prints: reproductions of oil paintings by the artist Christopher Still. The originals are on display at the Florida House of Representatives. Each print depicts some aspect of Florida in a style akin to history painting. The commanding gaze of Seminole Indian Osceola aims at the viewer in Patriot and Warrior (2001). Each hand gestures with conviction: one towards the sunset and an approaching Spanish vessel, the other gripped around a knife that pierces into a written document. This document “hangs” over the edge of the painting in a trompe l’oeil effect like the aforementioned murals at Lake Placid. An enormous alligator’s claws dangle over the borders of The Okeehumkee on the Oklawaha (2000). Each painting is concerned with narrative, landscape, and perspective: visual and historical.

The original is on display at the Florida House of Representatives in Tallahassee, Florida.

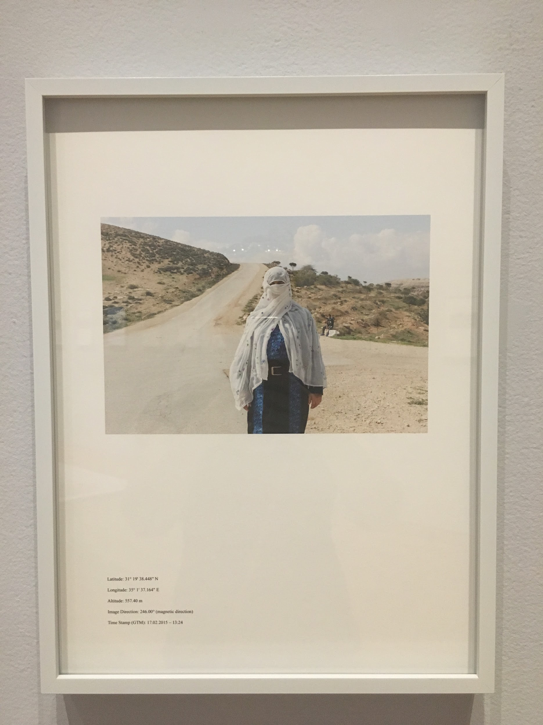

Anthony Record’s curatorial interests are similar. “I don’t organize exhibits with a strict, pre-existing philosophy or ideology, like ‘I’m interested in shows about identity’ or ‘I only focus on work by abstract artists,” he explains. “However, many of the exhibitions I organize seem to involve place. Location matters a lot to me and to many of the artists I exhibit.”

Location has mattered to Record personally, too. Originally from Tampa, Record received his bachelor’s from the University of South Florida. After earning his MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 2008, he returned to Tampa and has maintained proactive roles in the arts since. Most notably, Record is Co-founder and Director of the artist collective QUAID, which recently moved to Ybor City after almost a decade in Seminole Heights. Along with exhibition spaces like Tempus Projects and Parallelogram Gallery, QUAID was part of a community of enthusiastic, DIY artists and educators who promoted contemporary art in a city that was otherwise lacking.

Record complemented his executive role at QUAID with educational positions, adjuncting at the University of South Florida as well as various community colleges from 2010 to 2018. “I love teaching, but I definitely prefer teaching at community colleges,” he confesses. “The students tend to be more diverse in every way: age, socioeconomics, political affiliation, level of background. All the students are interested in art but tend to be less interested in credentials. They also tend to push back a little more, which often makes for a richer classroom experience.”

In 2018, Record stopped adjuncting to assume a full-time role at the Tampa Museum of Art. While no longer a professor in a college classroom, Record worked in the education department as the Studio Programs Coordinator, where he organized after-hours classes hosted by local artists. Children and adults alike would attend these classes to participate in a wide range of making. “The classes were only a few hours long, so they had to be engaging but concise. The topics depended on whichever artist hosted the event. They could range from self-portraits in acrylic to large-scale collage to simply paper sculpture.”

Record left his position at the TMA earlier this year to become the curator at MOFAC. “The job at MOFAC has several moving parts, which I enjoy,” he says. “The most obvious are the contemporary artist exhibitions. Artwork that involves Florida, whether the artist is a homegrown Floridian or not, doesn’t have much institutional presence. The same is true of general Florida history and archaeology. I know a lot of great artists whose work deals with this state and deserves the kind of authority and attention that an institutional solo show can offer. To pair those works side by side with objects of Floridian craft and archaeology, which have very different cultural and intellectual histories than art with a capital “A,” makes MOFAC an exciting exhibition space.”

Considering Record’s noted contributions to the Tampa Bay art scene, contributions about which several people have expressed their gratitude in casual conversations with me about Record, one wonders: why leave? Avon Park is not as far from Tampa as, say, Las Vegas, but it’s still a hike. Culturally, they’re almost polar opposites. Tampa, specifically the art scene of which Record is a notable architect, is “cool.” Under no circumstances is Avon Park. To my knowledge, Record previously knew no one in Highlands County. “The position at MOFAC popped up and seemed like a good opportunity,” he concludes.

Succinct, polite, evasive. I press, albeit gently, and like any schlocky interviewer, I make it about myself. I mention that I’ve moved around a lot for school and residencies. Within two months of meeting with Anthony, I had left a yearlong residency in Star, North Carolina to pursue a full-time job in Orlando, a city I hate in the lamest way possible. I have some family and acquaintances in Orlando, but not the community I had in Star, Tampa, or Boston. Being an artist grants you the flexibility to hop to new places and meet new groups of people, but it doesn’t make leaving them behind, if only by a few hours, any easier.

He agrees and elaborates on his decision. “I guess that the position at MOFAC seemed like a full-time version of my role at QUAID: providing young, hungry, interesting, local artists with exhibition space for their work. I’ve had mixed feelings about some of the places I’ve shown my work. As an exhibiting artist, I had a lot of disappointments with various galleries and museums; just the things that weren’t provided and the level of engagement with my work that I was hoping to get but didn’t. I hope that I can use those experiences to cultivate an exhibition space that is both more attentive to the needs of artists while also staying out of their way.”

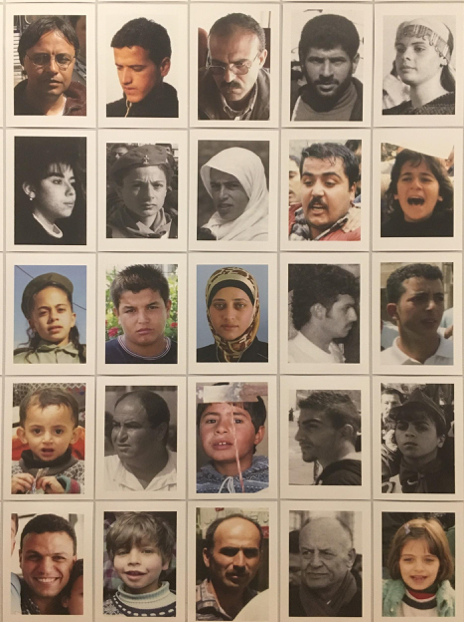

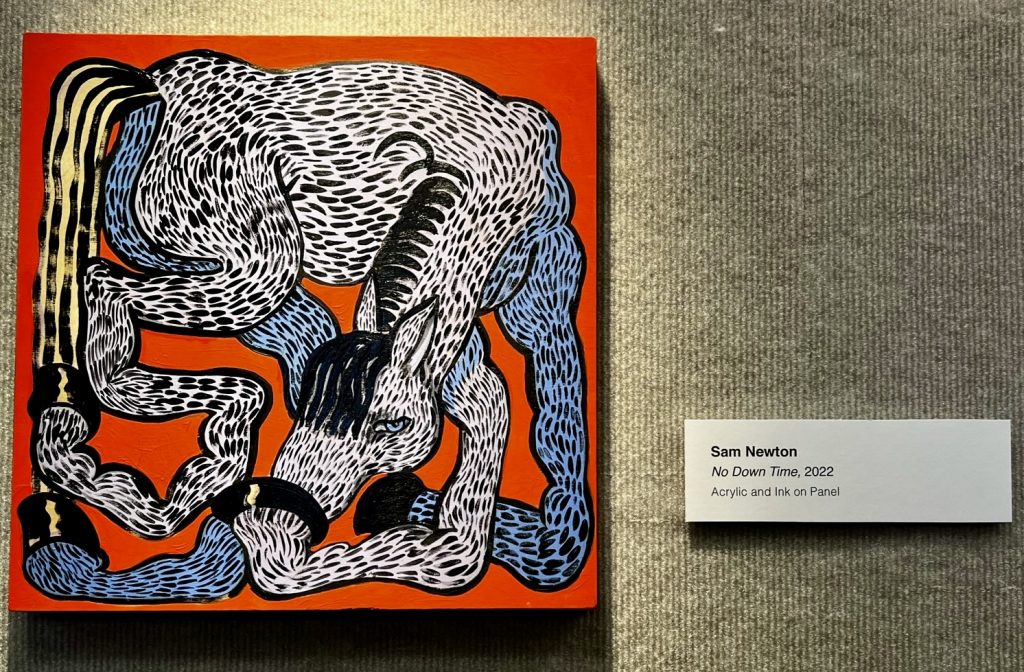

Whatever cocktail of circumstances led to Record’s decision, MOFAC is clearly lucky to have him. In just six months, Record has served himself a full plate: reorganizing the collection, changing the floorplan of the contemporary art galleries, securing future solo shows, writing exhibition didactics, planning gallery events, and developing an online presence via video interviews with exhibiting artists. These videos, crispy produced, are separate interviews with artists Bruce Marsh and Sam Newton, whose respective solo exhibitions A Long Glance and Herd of Thunder opened in early October of 2022 (Both exhibitions have since closed.) Marsh was a longtime professor at the University of South Florida and Newton is a current member of QUAID.

The videos are not just methods by which the museum can advertise online, however. They’re also not just interpretation tools for the viewer to glean deeper insights into the work, though they do that well. Record conducted these interviews and edited the videos, and his signature appetite for “place” is all over them. While Marsh and Newton discuss their interests and aspirations outright, each video underscores the setting in which these artists make art and presents a synopsis of their daily working life.

Granted, Bruce Marsh explicitly discusses how his home of Ruskin, Florida defines his work. What the video presents that isn’t immediately visible upon looking at Marsh’s work or listening to him speak is the kind of life that would produce such work: a contemplative life of teaching, commuting, and now retirement. Marsh moved to Ruskin as a compromise between he and his wife, Dolores Coe. She was teaching at the Ringling College of Art and Design and he was teaching at USF. Thus, the rural town of Ruskin was the middle point of their commutes.

Marsh’s paintings indicate someone who spends a lot of time looking around at the same things: the outlet malls off I-75, a brewing afternoon storm on the horizon, an intersection at sunset on the way home from work. What most of us would tune out, Marsh isolates and lovingly renders but without hyperbole. Instead, he purposely portrays them as what they are: ordinary, without exaggeration. One’s attention is drawn to these paintings because of their elegant execution of space, not because they depict recognizable people or distort the everyday into a spectacle. But when Record’s camera cuts from Marsh and lingers on an empty bridge or the charmingly dilapidated Ruskin Drive-In, neither of which are the subjects of Marsh’s paintings, the audience is handed more insight than anything Marsh could say out loud.

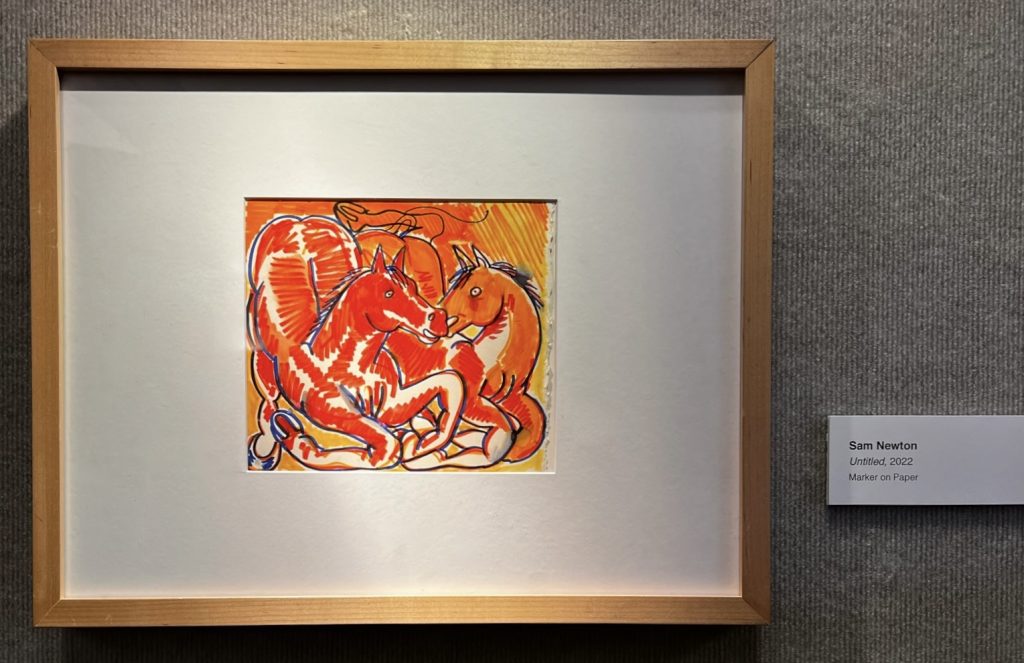

Since Sam Newton’s paintings aren’t really about location at all, Record’s focus on place is even more exposed in her video interview. Newton’s paintings have backgrounds, but they’re simplified to emphasize attention on the real subjects: horses, presented in all their buxom glory. Unlike Marsh, Newton isn’t interested in playing with perspectival space and ordinary locations. Newton’s interests, instead, lie in anthropomorphism and a comic sensibility akin to the infamous Foot of Cupid from Monty Python or the flat irony of stick-and-poke tattoos. Newton compresses her horses barely within the edges of the canvas to articulate just how robust, knobby, temperamental, vigorous, and fragile they really are.

Complicated creatures. And that’s just the artwork itself. Like Marsh’s interview, the main subject of Newton’s video is the particular configuration of her working life (I won’t say “work-life balance”). Unlike Marsh, Newton lives in trendy Seminole Heights but has no dedicated studio in her home, at least not one that we see. The generational contrast between the videos is sharp. Within the first minute, the viewer is presented with a domestic environment that is unmistakably Millennial. The living room, which doubles as Newton’s studio, is engulfed in potted plants, mostly palms. A slate gray housecat lounges on a cat scratcher that appears surprisingly manicured. A child’s cozy coupe outside is plastered with a bumper sticker that reads, in block print, “HONK IF YOU LOVE KING STATE.”

Another big difference: Newton has two young children. Julian, the oldest, doesn’t appear. The youngest, Valentine, unabashedly makes his presence known. Newton explains that she began these horse paintings during the COVID lockdowns and her subsequent pregnancy with Valentine. She admits that it’s easy for her to project onto horses because, “…they all have bangs.”

If only a little sarcasm covered our tracks like we hoped it would. Clearly, there are other reasons why vibrant horses in claustrophobic spaces might resonate with Newton: the pent-up isolation of COVID lockdowns? An analogy for pregnancy, where you share limited space with someone else? A representation of the compressed hours in a day of a working artist and mother? “[Acrylic paint] is a plastic so it’s drying faster, and it has a different texture [than oil paint],” she says, explaining her transition from using oils to acrylic. Newton loves how acrylic more readily accepts other media, from colored pencils to crayons to ink. Ostensibly, she’s come to prefer acrylic’s flexibility and expansiveness to oil’s stiffness. “The sky’s the limit,” she claims of acrylic. I object. More likely, it’s precisely the limits of acrylic that attracts Newton. Its swift drying time and uncomplicated working conditions provide a conclusiveness that she’s found compatible in her life. “I’m able to make work that I wouldn’t be able to make, in the speed that I make it, in the situation that I’m in right now,” she says, before glancing warmly over her shoulder at Valentine.

What provides me all this information, and what grants me a sense of access that, in turn, elicits some hubris within me to freely speculate about these artists’ lives, is Anthony Record’s quiet but guiding eye. Editing, directing, curating, producing: all these jobs require clear decision-making with as little trace of the author as possible. At least, that’s been Record’s hope for himself as curator at MOFAC. So far, it appears he’s succeeded. In six months, a set of interests and a graceful sensibility for articulating them has already emerged. The towns we decide to live in, our hours spent on the road or in offices, the slivers we carve out of our days to do the things we really want to do, the people with whom we choose to spend our “off” time: all the pragmatic compromises we make and their effects on creative work are under Record’s nonjudgmental microscope.

I’m sure Record’s recent move, like mine, feeds these interests even more. Like it or not, tradeoffs between work and life must be made. Like the artists he exhibits, Record has made a tradeoff that works well for him. Avon Park supplies the tranquility for focus and Record supplies the faithful attention to detail. With QUAID, Record is happily one of several making executive decisions. At MOFAC, he’s largely driving solo.

Bay Art Files contributor Jonathan Talit is an artist currently based in Orlando. He received his BFA from Boston University and recently received his MFA from the University of South Florida, Tampa. He makes sculptures, essays, exhibitions, friends, fun, and occasionally money.

Visit mofac.org for more information about the Museum of Florida Art and Culture and its upcoming exhibitions and programming.

Click here to watch the YouTube archived videos on artists Bruce Marsh and Sam Newton.

Visit anthonyrecord.com for more information about Anthony Record.

Visit quaidgallery.com for more information about the Tampa-based artist collective QUAID.