steven locke: the color of remembering

On view through March 7th at Hillsborough Community College’s Gallery 221 as part of an annual exhibition celebrating African American heritage and presented in conjunction with the Tampa Bay Black Heritage Festival.

steve locke: the color of remembering is on view at HHC’s Gallery 221 though March 7th.

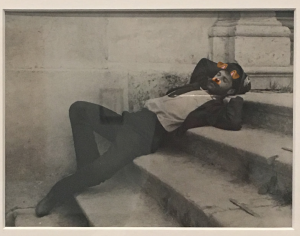

This exhibition examines how African Americans have been depicted in ways which betrays explicit and implicit cultural prejudices depending, in this case, the age of the memory. From schematic diagrams of slave ships, historical photographs of lynchings, to modern day video, brutality and racism – institutional or otherwise – images have been made and disseminated which tacitly imply values which we should, indeed, must find deplorable.

Not only by subject matter but, significantly, it is through the means of presentation that Locke employs in the photography series Family Pictures, 2016, that he addresses how different standards apply, in particular, that there isn’t an universal sense of respect and dignity when it comes to the memorialization of the atrocious. Locke himself memorializes images of the barbaric, setting them in unexceptional frames, engraved with the platitudinous and set against strong colored backdrops – notions of remembering and color are brought to the fore – the colors are strong but it is an overall sense of banality which is most provocative and the taint on remembering which Locke communicates most powerfully.

In Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie (A Memorial for Freddie Gray), Locke further confronts how there remains to this day a biased filter as to presentation of the African-American experience in the media. In this case, the tragic death of Freddie Gray on April 12th, 2015 whilst in the custody of the Baltimore Police Department. The intrusive and the demeaning combined with sensationalized reporting to ignore the dignity and suffering of this man. Validly, it might be asked had this not been a young African-American man whether the coverage would have taken on a different tone. By distilling the color palette of three commonly circulated photographs of Freddie Gray down to three hues of gray, Locke speaks to the debasement of this individual, his suffering and brutal death. Freddie Gray became a media-currency. His life and death had determined a value, that of a commodity. One that was exchanged between us and the news outlets. Locke shows us how we are complicit in this process, that the communication of outrage embraces complexities which have at their foundation the self same prejudices which they seek to make clear, here it is literally gray.

steven locke’s: the color of remembering at is a powerful exhibition. By bringing together the history of slavery, racism and subjugation through to the contemporaneous he threads a course of prejudices towards African Americans from the overt to the more hidden. It is instructive, in particular, how this exhibition focuses us on the modern day and practices which covertly but evidently seek to assuage the sensibilities of the mainstream at the expense of Black experience. The works themselves, are compelling and visually strong. The replication of composition in Family Pictures is one which has an unerring sense of imbalance. The images contained, framed with frames and repetitively composed powerfully suggest a diluting of content whilst, in fact, communicating the exact opposite. Steven Locke shows a consistent mastery of practice and sheer intellectual energy in working with the complexities of this difficult but very important subject matter. To be asked to re-think, indeed, re-remember and to give life and color to the challenging is the significant and worthy success of this exhibition.

At Bay Art Files, we have asked Tyra Mishell, who is pursuing a BA in Studio Art at the University of South Florida, to write about this powerful and timely exhibition. Her impressions of viewing the exhibition and meeting with the artist will post soon.