Marisol in Miami

By Katherine Gibson

Two figures sharing a meal together, Dinner Date from 1963, was my introduction to Marisol’s work. I gravitated to it right away when scrolling sculpture images several years ago. I was not familiar with the artist Marisol (Maria Escobar, Venezuelan-American, 1930-2016) but kept bookmarking images of these captivating, odd, intriguing carved figures with various details highlighted, an actual shoe here, a sculpted hand there. I was immediately fascinated by Marisol’s work and vowed to see it in person.

That opportunity came this summer when my good friend Jose Gelats and I learned that the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) was showing Marisol’s work in a traveling exhibition, Marisol and Warhol Take New York, organized by The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg, PA.

Driving to Miami took much less time than I remembered, and winding through the streets of South Beach was pure delight. Nothing compares to the authentic, historical, elegant Art Deco buildings, an architectural Disneyland in magical pastels. We stayed at The Whitelaw Hotel on Collins Avenue, one block up from Ocean Drive, and immediately found a delicious coffee shop nearby. Across the street, we stumbled into a tucked-away hotel bar complete with a kind (patient) bartender, Darrell, who put up with two chatty Kathys. He made delicious cocktails and even talked me into trying peanut butter bourbon which insulted me at first (bourbon doesn’t need a flavor) — however, it wasn’t terrible, and now I have a bottle of my own.

Our zigzagging drive to The Pérez the following morning took us through various neighborhoods, reminding me how tropical and lush Miami is — you can round the corner and feel like you are in a dense, colorful rainforest. Vivid beauty in every direction.

Once at the Museum, I made a beeline to Marisol’s work. I breezed past the entrance layout and introductory wall text in search of the larger free standing installations — Dinner Date being a favorite (top image) and The Party, one of her most well-known (below).

It was easy to become distracted by the wooden structures and how elements were presented. When I actually locked eye-to-eye with the figures, their features were superbly drawn and many were immediately recognizable as well-known newsmakers of the time.

Who is this person who can come up with such original configurations of mediums while simultaneously rendering identities and known personalities so well, yet in an unusual, unorthodox way? Marisol also incorporated objects and fabric, yet you weren’t initially aware of the materials — at least I wasn’t at first. I was so mesmerized by the whole chunky, blocky, wood figure, or figures, that the skill, meticulous craftsmanship, and sheer artistry of a face, body, or detail was discovered moments later — and then, I would marvel at her work all over again. I’m just so darn knocked out by her work.

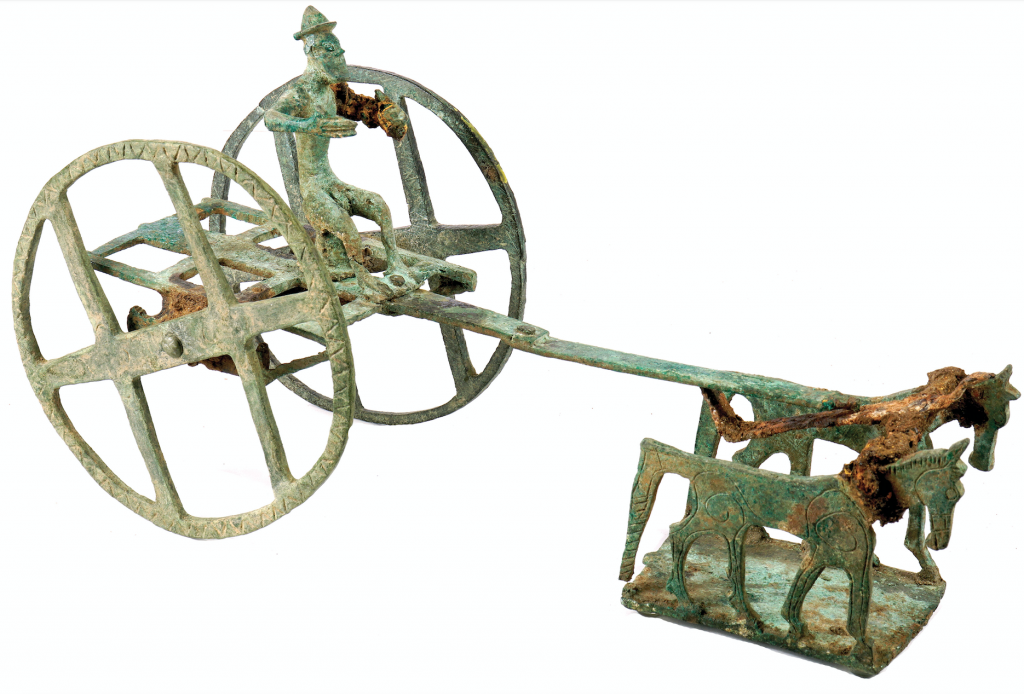

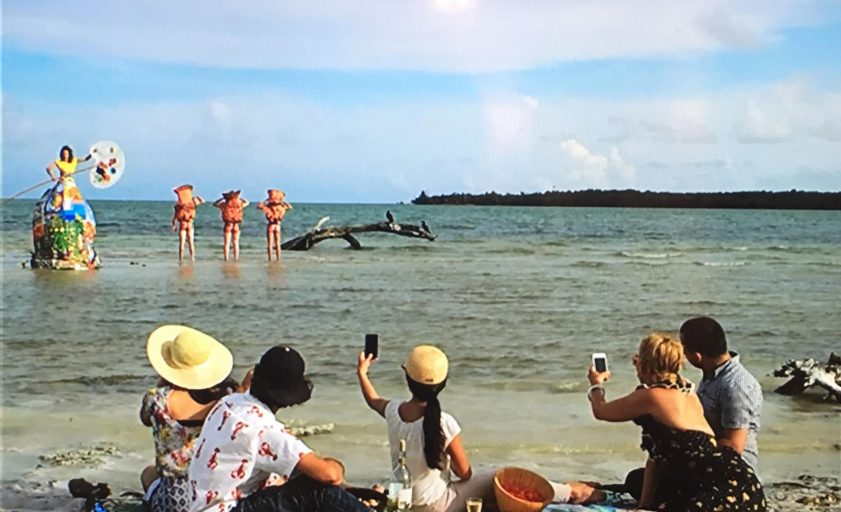

Standing amidst The Party guests — fifteen life-sized, carved figures in wood, each having its own dramatic flair and all sharing similar facial features — I was enchanted by the flourishes of each costume, the clever use of drama, and exposure. I also noted the aloneness of each figure — all were arranged together but hardly a connection between them.

The placement of Warhol’s loud pink and yellow cow wallpaper, running floor to ceiling behind The Party, was annoying. Obnoxious party crasher. I was incensed and confused. Why would you do that?

at the Pérez Art Museum Miami.

Listen to curator Jessica Beck from the Andy Warhol Museum discuss this particular work in a video walkthrough of Marisol and Warhol Take New York.

In one review I read, the author felt very much like I did but expressed the impact more clearly. “The only mistake in this display of “The Party” is the use of Warhol’s cow wallpaper as a backdrop, which grotesquely draws oxygen away from Marisol’s genius,” wrote Emily Cardenas of The Biscayne Times.

Below is an image of The Party without wallpaper distraction, as shown in The Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), where is it part of the Museum’s permanent collection. TMA’s published description of the installation reads, “As someone who always felt uncomfortable in the 1960s social scene, Marisol chose to display the figures in a setting where none of them interact with each other, many appearing entirely self-absorbed. By seeing these figures up close, you will also notice that each one shares similar facial features; Marisol often used herself as a model.”

For a fascinating discussion on this work, listen to Fashion & Alienation in 1960s New York with Dr. Halona Norton-Westbrook of the Toldeo Museum of Art and Dr. Steven Zucker of Smarthistory. Photo: Dr. Steven Zucker

Perhaps TMA could add an installation addendum requesting that the piece be shown without a background, ideally a plain white wall providing a clear and undistracted view.

Meandering through the full exhibition at PAMM, I noticed that a few other installations suffered from the wallpaper cacophony. Marisol’s wonderful sculpture of John Wayne on a horse — when you look straight at it — is almost erased due to the louder, bolder cow images behind the figure (see image). Warhol continues to mark his territory in ways that hinder views of Marisol’s work. Ironically, one of the few unencumbered views of Marisol’s work is her figure of Andy Warhol himself. Andy sits — as if on a throne — in a pristine, white corner.

Tricky to do, to show two very different bodies of work, together, created during the same timespan by two very different artists — both influenced by, and motivated by, the other. I find it interesting — fascinating really — to see how each chose to convey similar ideas. Marisol’s work, to me, just blows Warhol’s work away and I wince to see her unique authentic work watered down by an attempt to blend the less impressive work of another artist — or perhaps, in the opposite way, Marisol’s work shines even brighter because, when seen side-by-side, her work far surpasses Warhol’s.

“A lot of people will assume that Warhol was the famous one first, but really it was [Marisol],” says PAMM’s curator Maritza Lacayo in an art article that appeared in the Miami New Times. “There was so much about her that Warhol admired. She, in a way, inspired him.”

On our way out of town, we stumbled on the Laundromat Art Space, in the neighborhood known as Little Haiti, a clever re-use of an actual laundromat converted into a gallery and artist studios. Even though the building wasn’t open, we knocked anyway. And to our delight, an artist appeared and let us in and showed us around.

Jose and I are curious Nancy Drews at heart, and delight in aimless moseying. All we need is an inspiring anchor to organize around, and we are off and running. This last stop was a nice way to wrap up our indulgent, highly enjoyable road trip, spurred on by seeing Marisol’s work in person. Completely worth it — and really not that far from Tampa — a repeat round trip for sure.

As you drive here and there for the holidays, visiting — or escaping — family and friends, try taking the backroads instead of boring interstates; drop in a diner instead of a drive-through; visit a fruit stand instead of a jiffy store. Go in the direction of what gets your attention and tune out the obnoxious cow heads along the way.

About the exhibition

Marisol and Warhol Take New York debuted at The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg in October 2021 and was curated by Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art. On view at the Pérez Art Museum Miami from April 15, 2022, through September 5, 2022, it was organized by Franklin Sirmans, Director, and Martiza Lacayo, Assistant Curator.

About the author

Katherine Gibson, creator of ArtHouse3, is a regional art consultant and independent curator living in St. Petersburg, Florida. Gibson is the former Director of the Hillsborough Community College (HCC) Dale Mabry Gallery, which was rebranded Gallery221@HCC. Gibson received a 2018 Individual Artist Award from the St. Petersburg Arts Alliance for her Drive-by Window Project and was selected for an ArtsUp Grant by Creative Pinellas as creator and curator of the 2019 summer exhibition Tonge & Groove. Creating temporary exhibits in alternative spaces is a focus, and so far, has included storefront windows, empty lofts, rustic lake houses, and her home. Current projects include selecting artwork for various client environments, hosting exhibitions in ArtHouse Upstairs and writing the occasional piece for Bay Art Files.