In Good Company: Strength of Character at Creative Pinellas

by Jessica Todd

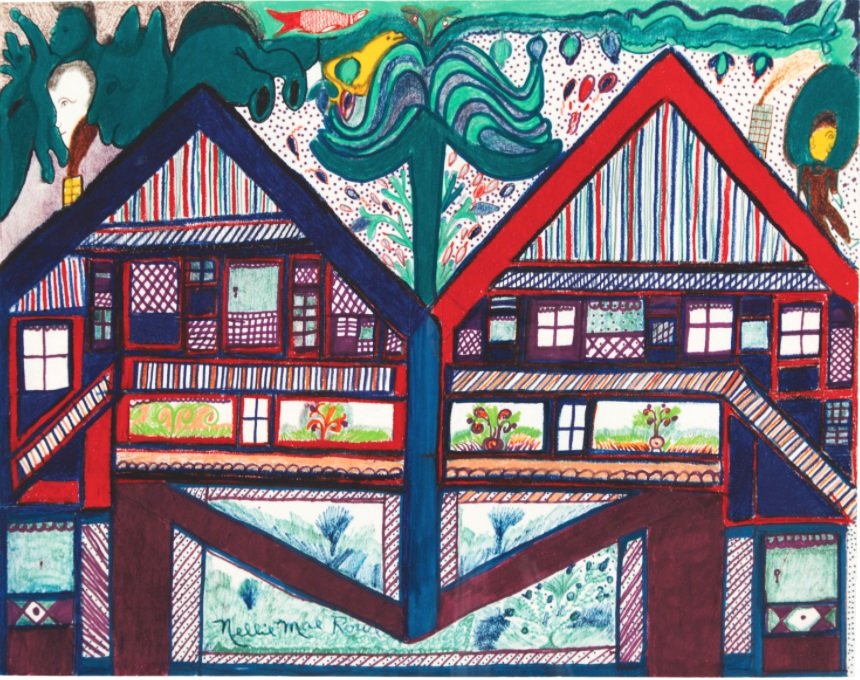

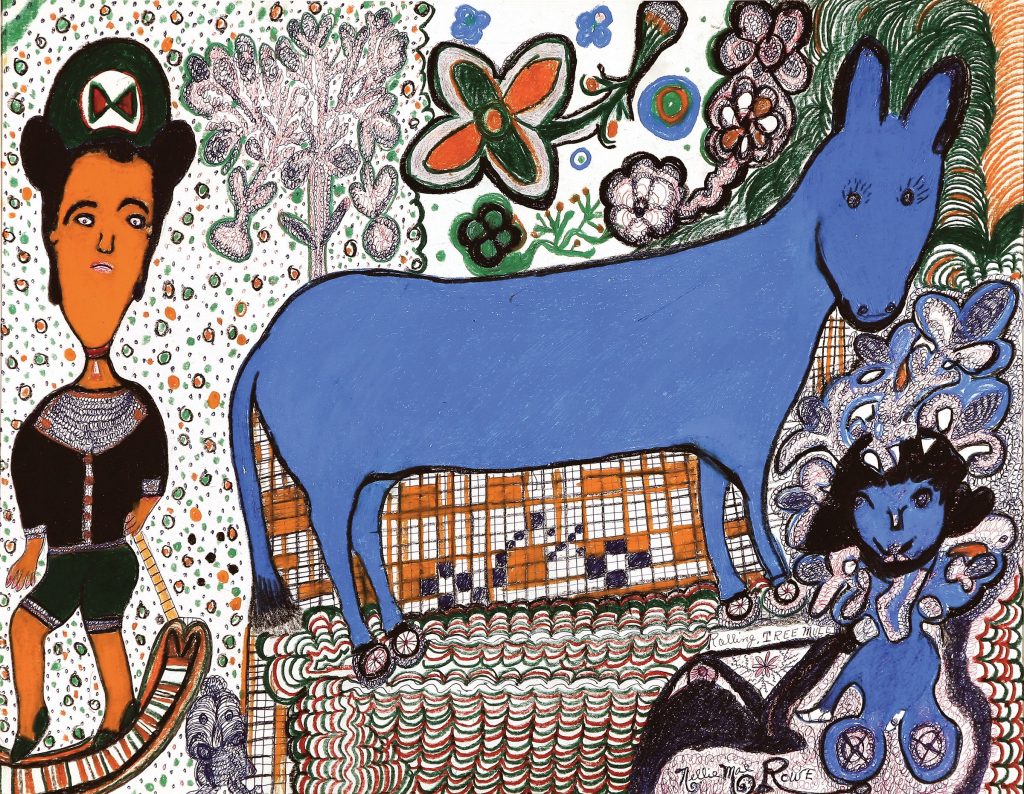

In her latest exhibition, Strength of Character at Creative Pinellas, curator Katherine Gibson welcomes the viewer into the gallery with warm familiarity. Oak seats and fruit chandeliers allude to home. Rich colors, natural materials, and hints of domesticity soften the formality of the impressively grand galleries of Creative Pinellas. There’s even a scent of cedar in the air.

The Art world is still shedding the restrictive boundaries between “Fine Art” and Crafts and Design. The Western Art canon has long excluded work due to medium, process, functionality, and proximity to the domestic. While oil painting and marble sculpture dominate the collections of major institutions and the pages of Art History books, a wealth of works in traditional Crafts media such as ceramics, wood, glass, fine metal, fibers, and paper have been largely ignored.

This exclusion is not due to a lack of artistic merit. Rather, it is deeply rooted in classism, racism, and sexism. Availability of materials, differing cultural applications of art objects, and restricted access to education and patronage led to different kinds of artmaking throughout history. To assert the dominance of the upper-class Western European male, the materials and functionality associated with the art of socially repressed groups were deemed inferior. And the tradition lives on.

Today, we see artists and curators challenging this bias. Audiences’ enthusiasm for Crafts media, Design, and functional work continues to push it into the mainstream. We see materials, processes, and forms we’re accustomed to living with in our homes now in gallery and museum spaces. This familiarity offers an entry point to the viewer. It democratizes Western art in a revolutionary way.

Gibson’s curatorial work is, in this sense, revolutionary. She integrates Crafts media with painting and sculpture, functional with conceptual work, and self-trained with academically trained artists. She integrates these works into the gallery seamlessly. Most importantly, her exhibitions are not “about” Art hierarchies. They’re about placing thoughtfully made artworks in a space and allowing them to converse with each other and with the viewer.

Strength of Character beautifully iterates this concept. We see the abstract paintings of Edgar Sanchez Cumbas next to the carved wooden furniture of David and Kathleen Bly alongside the sculptural installations of Kendra Frorup, which integrate printmaking, casting, and metalwork. Chandeliers converse with stretched canvas. Stools talk to framed paintings.

The harmony of the work in the gallery is a reflection of the collaborative installation process. The curator, artists, and Creative Pinellas staff came together to design an exhibition that is both cohesive and unexpected. Gibson isn’t afraid to ask the viewer to look upward or downward – “gallery height” is merely a suggestion. She’s a master of balancing scale in improbable ways: the Blys’ four petit Live Oak sculptures hold their own resting on the ground catty-cornered to Frorup’s wall-sized installation and substantial Sugar Apple Chandelier.

Each artist also contributed their unique perspective to the installation process: Frorup’s talent for collaging objects, Sanchez Cumbas’s eye for color and form, and the Blys’ engagement with architecture. Freddie Hughes (Gallery and Facilities Engagement Manager for Creative Pinellas) was instrumental in bringing the exhibition to life with his extensive installation knowledge and technical support. Serendipitous moments, like finding an old fence post outside to anchor Sanchez Cumbas’s Brush, or Frorup upending a utility cart from her studio to hold Banana Chandelier, reflect an openness to experimentation and play.

Though diverse in their media, the works in Strength of Character are united visually. Warm, rich earthy tones dominate the palette with intermittent pops of teal and quiet moments of textured white. Voluminous abstract shapes uncovered in the natural wood patterns of the Blys’ Live Oak series mirror Sanchez Cumbas’s explorations of human form in his Skinless series. Frenetic feather-like shapes in Sanchez Cumbas’s Compression Series and Reduction in Volumes are reflected in the crisscrossing screen- printed palm fronds of Frorup’s untitled installation. After seeing the symmetrical wood-turned bumps of the Blys’ work, Frorup responded with similarly shaped spun metal hardware to hang her Sugar Apple Chandelier.

Conceptually, all of the artists in the exhibition start with process. Frorup’s practice begins with collecting objects. She then problem solves through active making. Frorup engages in a range of art-making processes – from casting to papermaking to screenprinting – to arrive at her installations and sculptures. Her high regard for process is evident in her untitled installation featuring used screen-printing screens. The fruits that appear in Frorup’s work are an homage to her Bahamian roots and her mother’s farm that she grew up working on. Much like the artwork, the fruits are the sweet end result of a long cultivation process.

The Blys’ work is similarly driven by collected materials – reclaimed trees from Tampa’s urban neighborhoods. Their sculptures are a collaboration with the tree that bore the wood, which evolves throughout the making process. The tree tells them where to carve and when to stop. They work the wood while it’s still green, rather than fully dried, so that after their intervention the wood continues to bend, move, and crack. The resulting sculptures, many of which function as furniture, act as monuments to the downed tree from which they were sourced.

Sanchez Cumbas responds to the world around him through the cathartic process of painting. His kinetic brushstrokes in Compression Series and Reduction in Volumes reflect the turbulent war in Afghanistan and politics of 2010, when they were made (he notes, still relevant today). These works mark a turn from his figurative paintings, the last of which is Brush, also in the exhibition, a nod to the Buddha and his own Buddhist practice, a piece that is notably calmer and more grounded. The much more restrained works in the Skinless series sensitively explore bodies and skin, and issues around skin tone in the Latinx community. Each piece is a visual reflection of the emotion with which it was created.

It’s evident when speaking with Gibson and the artists of Strength of Character that they all share an immense respect for each other’s practices. The joyful spirit with which they engaged in this collaborative project is palpable in the gallery, and reflected in the enthusiasm of Creative Pinellas’s passionate staff. Head to Largo and make yourself at home in this beautiful exhibition, up through April 28, 2024.

A special thanks to the Gobioff Foundation for supporting this exhibition through their Microgrant program.

Creative Pinellas is Pinellas County’s non-profit local arts agency providing funding and support to artists while connecting businesses, tourism and the public with the arts community.

Jessica Todd is a curator, writer, and artist based in Tampa, Florida. She is passionate about building the creative infrastructures that support artists, and studying and addressing issues of equity, access, and inclusion in the arts. In October 2022, Jessica opened Parachute Gallery in Ybor City, first serving as an exhibition space for national artists and later a retail gallery representing local artists. Parachute Gallery currently operates remotely through online resources and off-site programming. Jessica has worked with a number of arts organizations since moving to Tampa in 2020, including Tempus Projects, Artspace Tampa Initiative, Crab Devil, and the Morean Arts Center. For six years, prior to moving to Tampa, she was the Residency Manager for the Rauschenberg Residency in Captiva, Florida. Jessica holds an MFA in Jewelry/Metals/Enameling from Kent State University, a BA in Art from Penn State University, and a Diploma of Hispanic Studies from the University of Barcelona.

Photography credit: Jessica Todd