The Nellie Mae Rowe story via Cincinnati

By Katherine Gibson

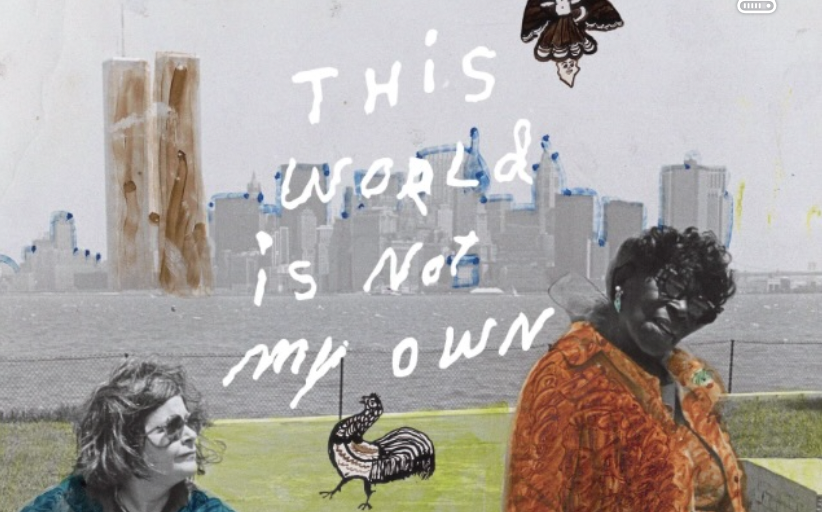

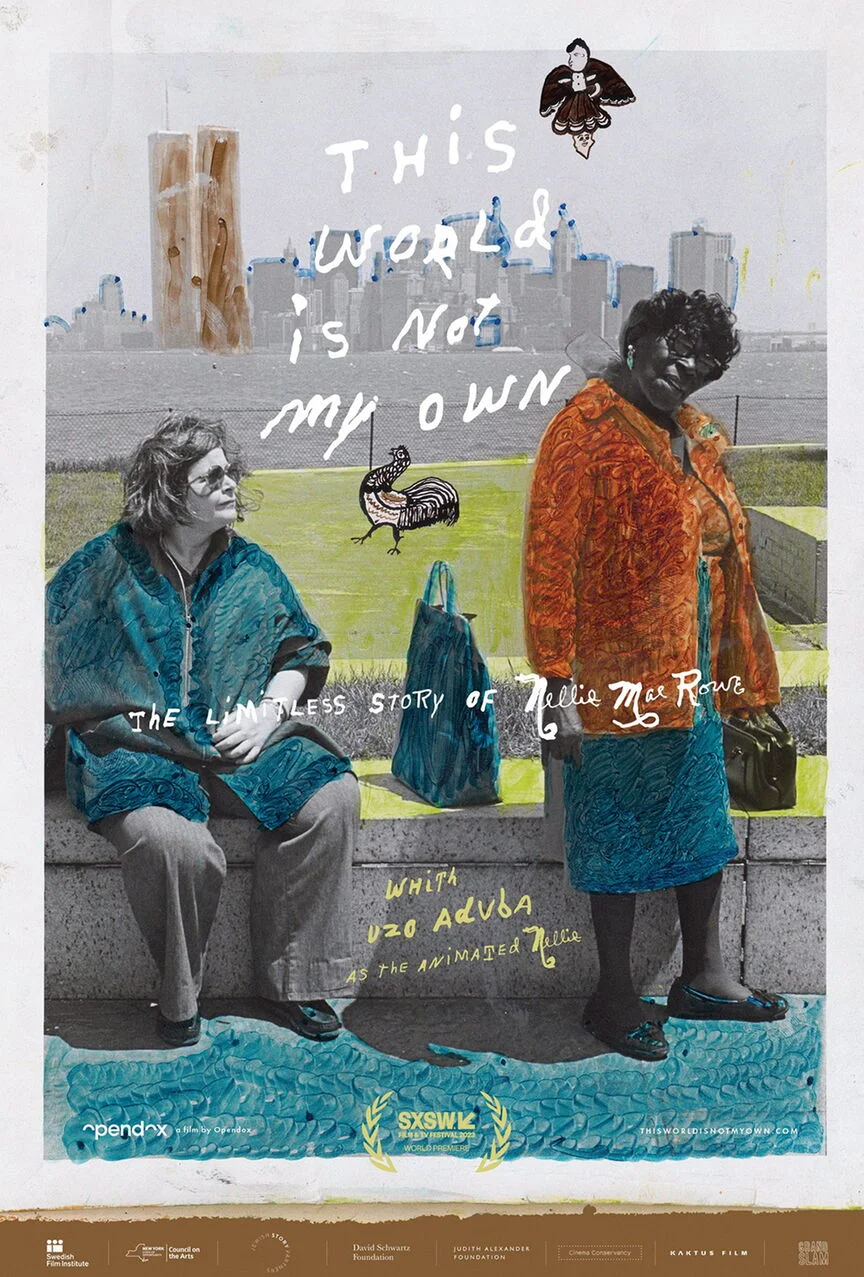

Ever since I saw the meticulous model of Nellie Mae Rowe’s Playhouse, which was created for the 2023 documentary about her life, titled This World Is Not My Own: The Limitless Story of Nellie Mae Rowe (TWINMO), I have wanted to see the film.

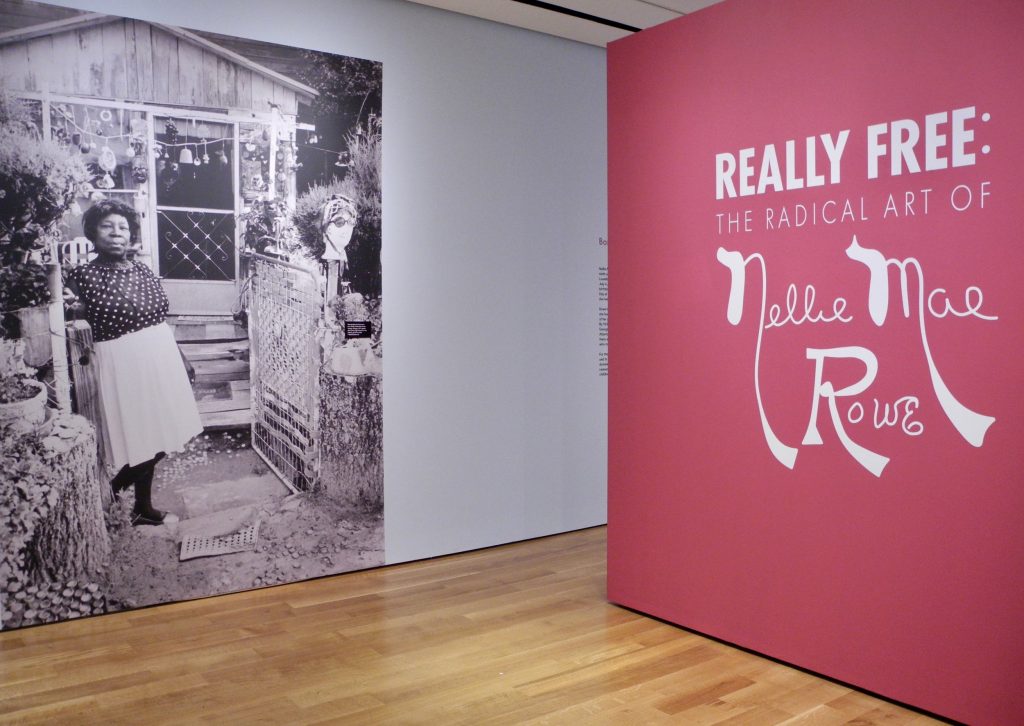

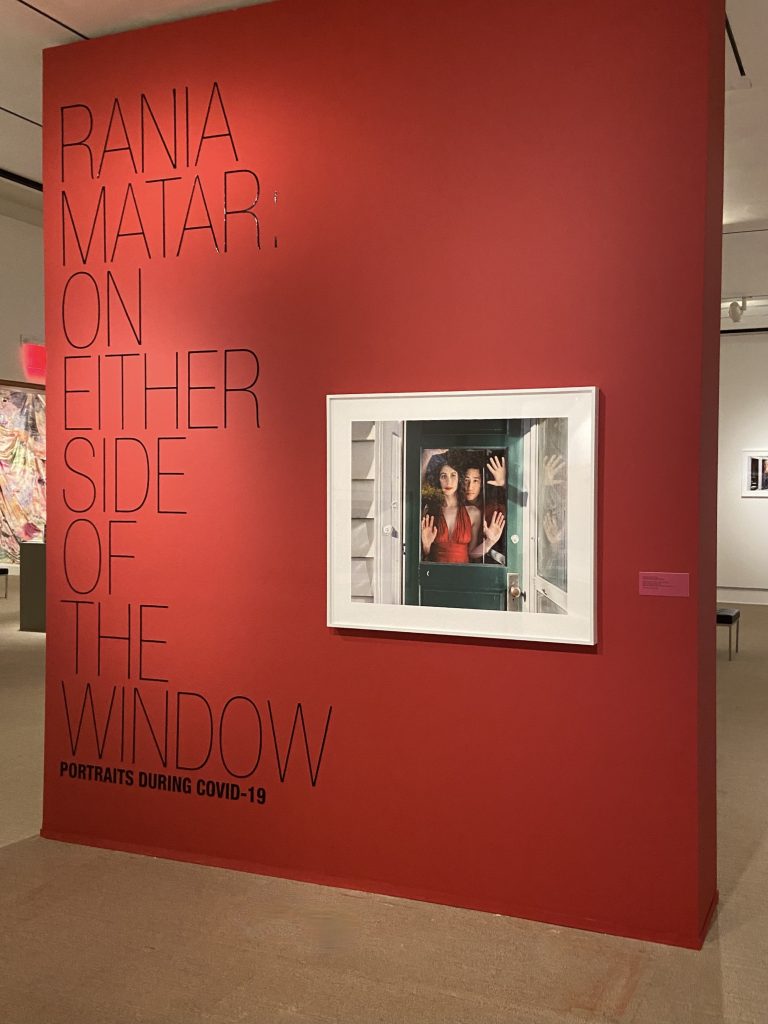

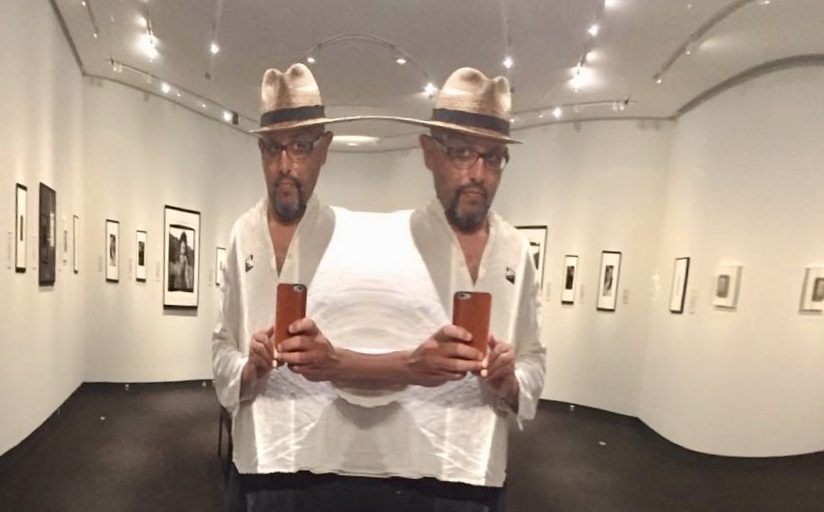

High Museum of Art, Atlanta (September 3, 2021 – January 9, 2022) Photo: K. Gibson

I wrote about the model in a previous 2021 Bay Art Files article when I reviewed Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. The film is now out and a screening was scheduled in late August at the Cincinnati Art Museum. There happened to be a 21c Museum Hotel not far, so my decision was made. I would see the film, stay at the 21c, take in Cincinnati and write about all of it! I snapped out of my summer slump, rejuvenated to have plans and an assignment. (In case you didn’t know, I am the official roving correspondent for Bay Art Files – Atlanta, Miami, Nashville, and now Cincinnati.)

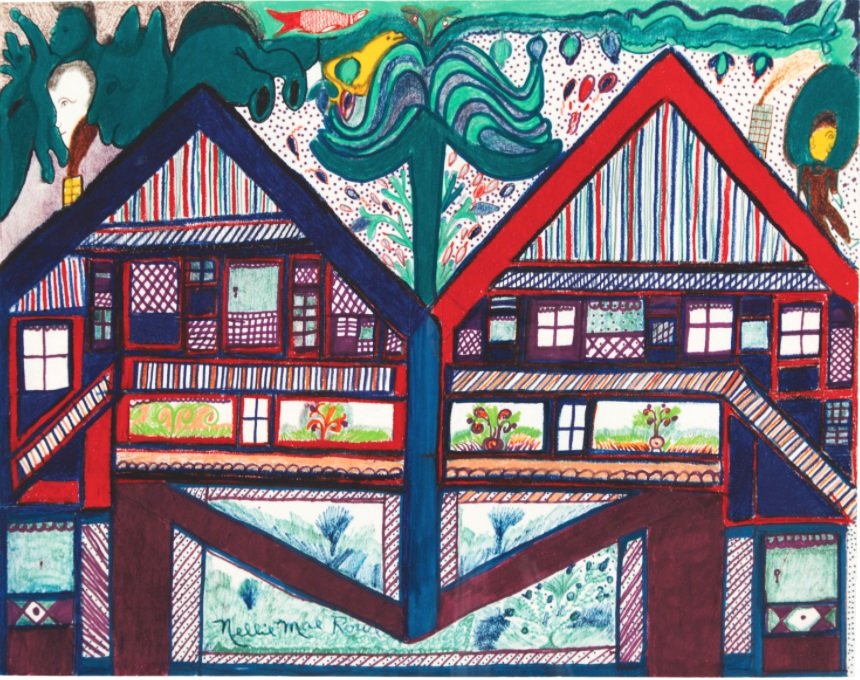

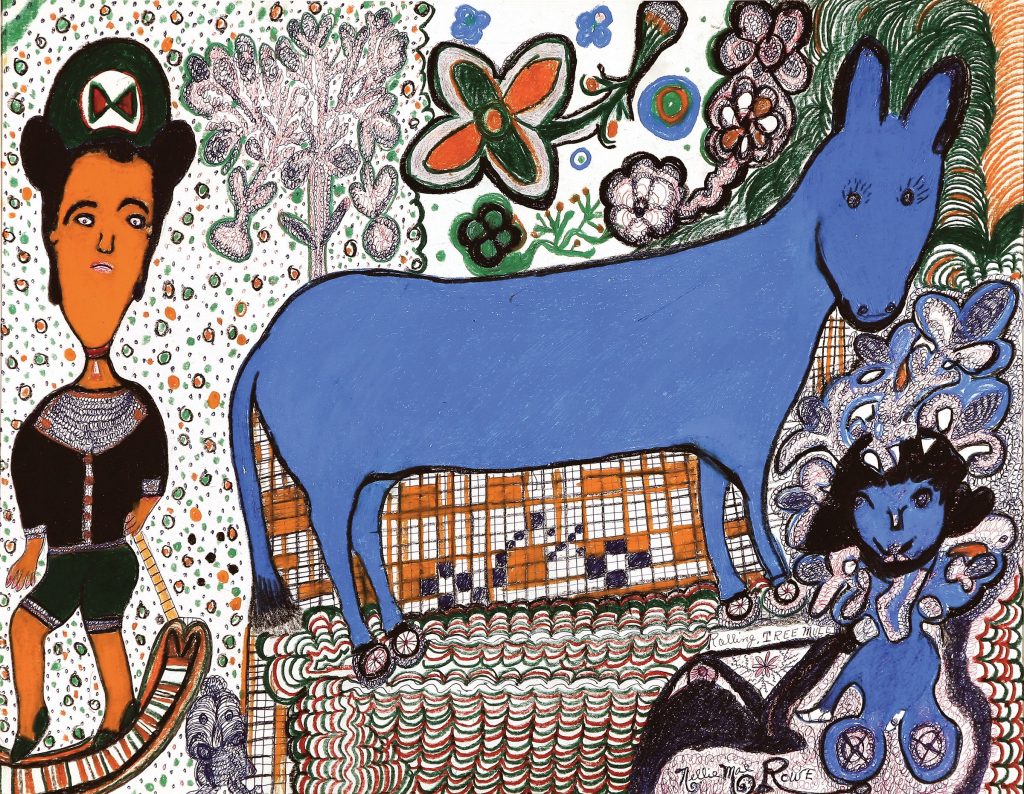

The screening of This World Is Not My Own was part of the Cincinnati Art Museum’s programming during Creating Connections, Self-taught artists in the Rosenthal Collection, which included a Nellie Mae Rowe crayon-on-paper drawing, titled Pink Pig. The accompanying wall text read: “Her whimsical compositions feature animals and other motifs drawn in saturated, jewel-like colors. Here, the calm simplicity of the pig enclosed in a heart is in contrast to the rest of the drawing crowded with animals, a human figure, and a large flowering tree.” I think of Rowe’s actual Playhouse as like the image in Pink Pig, a centered, creative calm in the midst of encircling influences. (To understand the context of The Playhouse, see the previous Bay Art Files article The Important Work of Nellie Mae Rowe.)

The World Is Not My Own was screened at several film festivals in the Spring and recognized for Best Cinematography at the 2023 Atlanta Film Festival and the film has received 100% on Rotten Tomato’s tomatometer (an amalgamation of film and television critics recommendations). Festival programming promoted TWINMO as “a documentary film that traces the lifespan of artist Nellie Mae Rowe through motion capture technology to replicate human expressions and movement, performed by actor Uzo Aduba.”

As a result, there are some well-written reviews, excerpts of which I will share.

Sheri Linden, of The Hollywood Reporter: “…Rowe took her independence seriously, as the captivating film portrait This World Is Not My Own makes vibrantly clear. After years of farm work and many more years as a domestic servant, the twice-widowed Georgian decided, in the powerful words of one of her great-great-nieces, ‘to design my life the way that I want it while I’m on this journey passing through.’ Linden goes on to describe the Playhouse: “Rowe turned her house — alas, no longer standing — into the Playhouse, filling it with her art, hanging the trees in the yard with her creations as well as found-object adornments, and inviting friends, neighbors and strangers to explore. There were drive-by harassers lobbing rocks and firecrackers at the ‘hoodoo witch,’ but there was also Judith Alexander, scion of a prominent Atlanta family who would become Rowe’s friend, gallerist and champion.”

Golden Globe entertainment journalist Brent Simon writes: “Stylistically, This World Is Not My Own challenges documentary conventions in its mixture of forms and, most especially, its editorial construction. Working with editor Princess Hairston, co-directors Petter Ringbom and Marquise Stillwell execute a narrative vision attached more to feeling than strictly linear storytelling.“

The way the creatures of the film swirled in stories linking personal interviews with historical footage was masterful, magical really. Never moving too far away from Rowe’s artistic interpretations, fragments of her dream-like drawings would start to fill the screen as though Rowe was drawing in real-time. Because the film is not linear, it’s so much more “Nellie.” Rather than a consecutive storyline, the film is more a collection of stories woven together by elements of Rowe’s drawings, serving as a whimsical narrator, a colorful through-line, transitioning from one story to the next.

The many entertaining and insightful interviews with leaders of the time, museum curators, friends and family provided glimpses of Rowe’s personality and her generosity in sharing her Playhouse environment. One family member said – with a big smile and a chuckle, “She was a fun-going lady.” I especially enjoyed learning more about the unique and beautiful friendship between Rowe and her gallerist, Judith Alexander which is an important and relevant focus of the film.

At a gathering honoring Alexander’s life (shared on JA Foundation site), the artist’s great-grandnieces, Cheryl Mashack and Cathi Perry, described the unique relationship between Judith and Nellie Mae, using a quilt analogy: “The focal point consisted of two people Judith Alexander and Nellie Mae Rowe, although two different textures they were cut from the same cloth. Their business acquaintance grew into a relationship and from that into a wonderful friendship and from friendship into family that has spanned over two decades. Judith had a passion for art — especially Nellie Mae’s art — and together with their eccentric and often quirky ways they started to stitch the fabric of all our lives together. Judith with her big heart extended herself not only to Nellie but to Nellie’s family as well.….Judith had an unassuming manner but a very forthright way in getting her point across and letting you know exactly how she felt, and with this came her unyielding zeal to expose Nellie’s work to the world because of the joy it brought to her heart. She wanted this joy to become contagious to all those around her; however it was very difficult for her to part with any of her “Nellie’s” as she so affectionately called them.”

Marquise Stillwell, one of the film’s creators and directors, was present at the Cincinnati Art Museum and entertained questions after the screening. He described the making of the film taking 6 years and went on to say (paraphrasing), the film mixes traditional documentary techniques with 3-D animations and scripted scenes shot using the Playhouse models and created sets.

Following the film, I returned to 21c moments after the dining room closed, however, room service was available – score! The bartender made me a Basil Hayden Old Fashioned (big grin) to keep me company while waiting for a room delivery of seared sea scallops served with corn grits, rainbow chard and honshimeji mushrooms. It was damn good.

Morning coffee was set up in the restaurant hosted by one of the life-sized golden yellow penguins which is the 21c Museum Hotel designated color for Cincinnati. The penguins turn up around the property and play various roles in greeting, guarding and generally marking their territories. 21c Museum Hotel Cincinnati is a boutique hotel, contemporary art museum, and restaurant housed in downtown Cincinnati’s former Metropole Hotel, a 100-year-old landmark listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Among one of the largest private art museums in the United States, it is North America’s only collection dedicated solely to art of the 21st century.

There’s something about historic buildings that don’t always translate into welcoming, spacious lobbies – depending on previous configurations. I love a pronounced main entrance or a snappy foyer that properly greets you and peaks your curiosity at the same time. I found this particular 21c entrance confusing and oddly configured — wasn’t actually sure I had walked through the intended door. But then, my eye caught sight of a strange scultpural figure in the lobby, also a huge vivid purple photographic landscape, both part of 21c’s current exhibit, “The SuperNatural”. Short attention spans are not always a negative. Something I do love about 21c environments is their clever use of common areas and unexpected niches as exhibition space — often to my surprise and always to my delight. Given my short stay, I wasn’t able to take in the full exhibition like at other 21c locations I’ve visited (Durham and Nashville). The remaining five Museum Hotels are in my future. A colorful penguin punch card is underway.

Before hitting the road, I made a beeline for a recommended place to get a good Reuben – just a few blocks away. Downtown Cincinnati was bustling and I walked through an active town square — it was a perfect day — coolish and clear. Most of the people I saw or encountered were young — or at least younger than me — and I wondered if that was a city trait or just me feeling older. Later, I learned the diner I visited was an authentic old-school Cincinnati diner, Hathaways, there since 1957. One of those things you “stumble on” if you ask the right local. The Reuben sandwich was perfect, complete with ridged and broken Lay’s potato chips.

A final serendipitous treat occurred en route to the airport. From the backseat of my taxi, I saw a spaceship — yes, a spaceship — midway up a distant hillside, across Kentucky’s border. An all too familiar tie to the Tampa Bay area.

The Cincinnati Art Museum, 21c Cincinnati Museum Hotel, This World Is Not My Own, downtown Cincinnati — a complete sensory overload — any one of these experiences begs for more time to properly absorb and enjoy. I’ll be back!

Note from the author: Arthouse3 and Bay Art Files are currently working on bringing the film to St. Petersburg, Florida. To do this, we will need movie ticket buyers, a few volunteers and sponsorship dollars to bring in one of the directors to speak about the film. If you have an interest in any of these roles, please let me know soon. The number of committed individuals could sway the schedule! (kg@arthouse3.com)

Katherine Gibson, creator of ArtHouse3, works with clients to find and place regional art, objects and furniture. Gibson is an independent curator, art consultant and creative design maker-upper living in St. Petersburg, Florida.