Our Country’s Family Pictures: Here and Now

Tyra Mishell

Walking into this exhibition,

I had the privilege of attending Steve Locke’s artist talk at the opening of the show and hearing him talk about the subject of the work was helpful in understanding Family Pictures in today’s political and social climate. After the talk and we spent some time discussing the spectacle nature of “Black Death” in the media. Violence towards Black people often goes viral in a sensationalized way. It feels like the announcement of a new “Black Death” is like the release of the most current iPhone. The hype comes and goes like new technology and returns when replaced with the next one. Media outlets delight in providing the public with new and exciting footage for controversy’s sake. In his exhibition statement, Locke goes on to write: “You can see a video, repeatedly (or even as a background image) as two people discuss a man being strangled or shot. To death. The prohibition of showing the deaths of victims is waived when the victim is black. Their last words are broadcasts. Their bodies left in the street as a warning, or as a provocation. You cannot imagine seeing the victims of Columbine or hearing the tapes of Sandy Hook, but for some reason, you can see a black man killed on your television. You can sit in a pub, a waiting room, your well-appointed home with its flat screen tv and see someone killed. These images are public and private and downright quotidian.” The images that we see every day are not coincidental, but deliberate attacks. It is about power and dominance. Our ability to spread information quickly has resulted in a different kind of cultural consciousness.

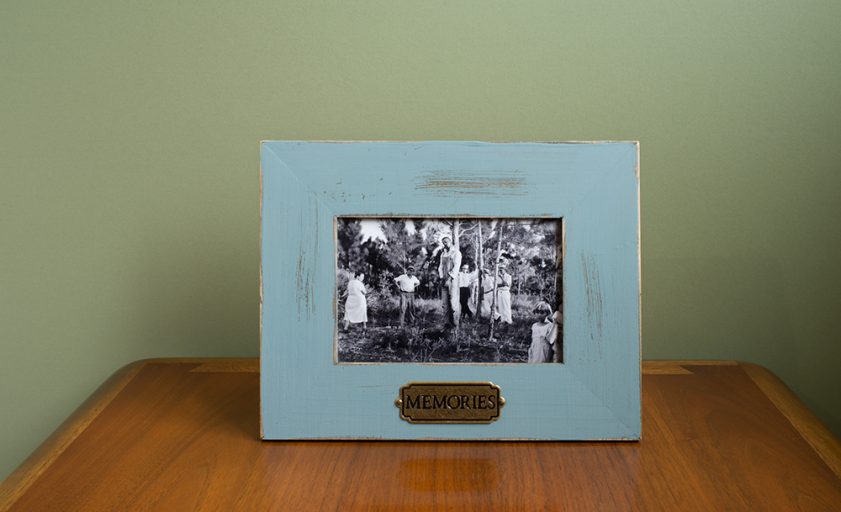

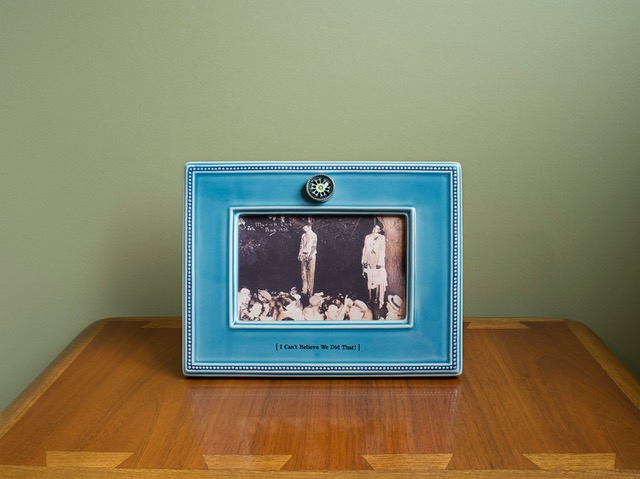

Two works in particular that have been stuck in my memory for weeks are Untitled (I Can’t Believe We Did That!) and Untitled (Mother). Both photographs involve something so uncomfortable literally reframed into something more pleasing, more palatable to look at. The frames resemble mass-produced picture frames with someones staged memory inside. Looking at Untitled (I can’t believe we did that) in all of its pretty blue glory seriously messed me up. The photo shows the lynching of two Black men (Thomas Shipp and Adam Smith) in Indiana in the year 1930. Below them, is a crowd of white spectators pointing at their bodies and looking at the camera. At the bottom of the frame, it reads “I Can’t Believe We Did That!” This historical picture was originally produced as a postcard, a keepsake, a pleasant memory. It is a funny statement. I’ve heard many variations of “I Can’t Believe We Did That!” From white people apologizing to me about slavery, Jim Crow, and police violence. I imagine the white people in this picture to have thought the same way. I imagine that they too could not believe that they were lucky enough to get such good seats at a hanging and be able to memorialize it.

I am always drawn to images representing Black womanhood, especially ones that involve racial archetypes. I believe that it is important to remember and notice the roots of these inherently violent stereotypes. In Untitled (Mother) we immediately associate the woman in the picture as a caretaker or the “Mammy” archetype. According to a source, the woman is Mattie Lee Martin and the image is dated between 1950-1960. It is a beautiful portrait, with Mattie Lee Martin smiling while holding up a cheerful looking white baby. The text underneath the photo reads “Because of you, my world is a better place.” The narrative behind the Mammy character would claim that she would have loved the child as she would love her own and that she would have been content in her domestic role. The quote on the frame is a true statement. In this country, Black women have had to survive. As apart of her survival she has had to maintain the lives of white families, and raise them up through her mental, physical, and emotional labor. I think of this now in a contemporary context. I think of myself when navigating white spaces. I think of myself having to coddle white folk’s feelings when they’ve mistreated me. After reflecting on my own interpretations of the work, I thought about how non-black people were responding to the pictures. I ignored the weird, sympathetic, and disbelief that was coming from their mouths. I wanted to know how their insides felt.

I love how Locke’s work forces us to acknowledge the disconnect between the dominant culture and everybody else. I believe that the disconnect is both subconscious and conscious. The circulating of the past photos used in Family Pictures resemble the 24/7 unproductive and dehumanizing distribution of Black Trauma in the present. We want to remember these atrocities as atypical and that only the most evil people were complacent. We want to remember it all as a rarity. We want to believe in the “good ones.” As we refuse to recognize this as tradition and common practice, we continue to silence the oppressed and commit ourselves to misunderstand.

Tyra Mishell was born and raised in Bradenton, Florida in 1994. She is currently residing in Tampa where she will receive her BA in studio art from the University of South Florida in Spring 2019. She is a New Genres artist specializing in video, new media, sound, and performance. With a combined interest in media studies and the make believe, she produces IN SPACE TV, an experimental net-based television show.

steve locke: the color of remembering is on view at Hillsborough Community College’s Gallery 221@HCC on the Dale Mabry campus through March 7, 2019. In addition to the photographs from the 2016 Family Pictures series, there is an installation of Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie (A Memorial for Freddie Gray). Locke is an Associate Professor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston, MA.

Tampa-based artist Omar Richardson exhibits large black and white woodblock prints and unique